По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

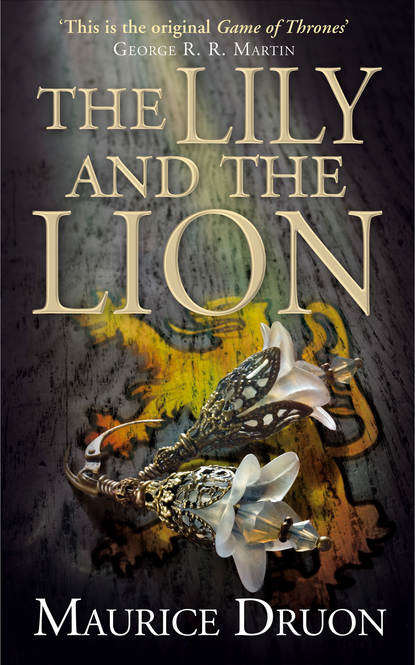

The Lily and the Lion

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I give my counsel, in right of being the oldest member present, that the Count of Valois, who is nearest to the throne, be Regent, Guardian and Governor of the realm.’

And he raised his hand to show that he was casting his vote.

‘He’s quite right!’ Robert of Artois said quickly, raising his great paw and looking round at Philippe’s supporters to make sure they followed his example.

He was almost sorry he had had the old Constable cut out of the royal will.

‘Agreed!’ said the Dukes of Bourbon and Brittany, the Counts of Blois, Flanders, and Evreux, the bishops, the great officers of State, and the Count of Hainaut.

Mahaut of Artois caught the Duke of Burgundy’s eye, saw he was about to raise his hand, and hastily approved so as not to be the last. But the look she gave Eudes signified: ‘I’m voting for your choice. But you’ll support me, won’t you?’

Orleton’s was the only hand not raised.

Philippe of Valois suddenly felt utterly exhausted. ‘It’s all right, it’s all right,’ he thought. He heard Archbishop Guillaume de Trye, his old tutor, say: ‘Long life to the Regent of the Kingdom of France, both for the good of the people and for that of Holy Church.’

The Chancellor, Jean de Cherchemont, had already prepared the document which was to embody the Council’s decision. He had only to insert the Regent’s name. He wrote in a large hand: ‘The most powerful, most noble and most dread Lord Philippe, Count of Valois.’ Then he read out the Act which not only assigned the Regency, but declared that, if the child to be born was a girl, the Regent was to become King of France.

All present appended both their signatures and private seals to the document. All, that is, except the Duke of Guyenne in the person of his representative, Bishop Orleton, who refused, saying: ‘One has nothing to lose by defending one’s rights, even if one knows one cannot succeed. But the future is long and lies in God’s hands.’

Philippe of Valois went over to the catafalque and gazed at his cousin’s corpse, at the crown upon the waxen brow, the long gold sceptre lying on the mantle and the golden boots.

They thought he was praying, and his act earned their respect.

Robert of Artois went to him and whispered: ‘If your father can see you at this moment, the dear man must be delighted … There are only two months to wait.’

4. (#ulink_944d3ee2-8cb6-51a1-a091-84314a7223cb)

The Makeshift King (#ulink_944d3ee2-8cb6-51a1-a091-84314a7223cb)

PRINCES OF THAT TIME always had to have a dwarf. Poor people almost considered it a piece of good fortune to bring one into the world; they were sure of being able to sell him to some great lord, if not to the king himself.

A dwarf was generally looked on as ranking in the order of creation somewhere between a man and a domestic animal; he was animal because you could put a collar on him, rig him out in grotesque clothes like a performing dog, and kick his backside with impunity; on the other hand, he was human in so far as he could talk and submitted voluntarily to his degrading role for food and pay. He had to clown to order, skip, cry and play the fool like a child, even when his hair had turned white with advancing years. His lack of inches was proportionate to his master’s greatness. He was bequeathed like any other piece of property. He was the symbol of the ‘subject’, of nature’s subordinates, expressly created, so it seemed, to be a living witness to the fact that the human race was composed of different species, of which some had absolute power over the rest.

Abasement nevertheless brought certain advantages, for the smallest, weakest and most deformed in the community were among the best-fed and the best-clothed. Moreover, the dwarf was permitted, indeed commanded, to say things to the masters of the superior race that would not have been tolerated from anyone else.

The mockery and even the insults that every man, however devoted he may be, occasionally addresses to his superior in his thoughts were vented, as it were by delegation, in the traditional and often singularly obscene familiarities of the dwarf.

There are two kinds of dwarfs: the long-nosed, sad-faced hunchback, and the chubby, snub-nosed dwarf with the body of a giant supported on tiny, rickety legs. Philippe of Valois’ dwarf, Jean the Fool, was of the second kind. His head barely reached to the height of a table. He wore bells on his cap, and silk robes embroidered with a variety of strange little animals.

One day he came skipping and laughing to Philippe and said: ‘Do you know what the people call you, Sire?’ They call you “the Makeshift King”.’

For on Good Friday, April 1st, 1328, Madame Jeanne of Evreux, Charles IV’s widow, had been brought to bed. Rarely in history had the sex of a newborn child created such excitement. When it was known to be a girl, everyone recognized it as a sign of God’s will, and there was great relief.

The peers had no need to reconsider the choice they had made at Candlemas; they assembled at once and unanimously, except for the representative of England who objected on principle, confirmed Philippe in his right to the crown.

The people also heaved a sigh of relief. The curse of the Grand Master Jacques de Molay seemed exhausted at last. The Capet line, at any rate in its senior branch, was now extinct. During the last three hundred and forty-one years it had given France fourteen successive kings, though the last four had reigned for no more than fifteen years between them. In any family whether rich or poor, the absence of male heirs is considered, if not a disaster, at least a sign of inferiority, In the case of the royal house, the inability of Philip the Fair’s sons to produce male descendants was looked on as a punishment. But now there was going to be a change.

Sudden fevers seize on peoples, and their cause must be sought in the movements of the planets since no other explanation can be found for them. How else account for such waves of hysterical cruelty as the crusade of the pastoureaux or the massacre of the lepers? How account for the tide of delirious joy that accompanied the accession of Philippe of Valois?

The new King was tall and endowed with the majestic physique so essential to the founder of a dynasty. His elder child was a son, already nine years old and seemingly robust; he had also a daughter, and it was known (Courts make no secret of these things) that he honoured his tall, lame wife almost every night with an enthusiasm the years had in no way abated.

He had a loud and resonant voice, unlike his cousins, Louis the Hutin, and Charles IV, who had stuttered; nor was he inclined to silence as had been Philip the Fair and Philippe V. There was no one who could oppose him, no one who could be put up against him. Amid the general rejoicing, who in France was going to listen to a few lawyers paid by England to draw up objections, which they did without much conviction?

Philippe VI ascended the throne with the consent of all.

And yet he was King only by a lucky chance; he was a nephew and a cousin of kings, but there were many such; he was simply a man who had been luckier than his relations. He was not a king born of a king to be king; he was not a king designated by God and received as such, but a ‘makeshift’ king, who had been made when one was needed.

Yet the popular nickname in no way detracted from the loyalty and rejoicing; it was simply one of those ironical phrases the populace so often uses to mask its emotions and make itself feel that it is on close and familiar terms with power. When Jean the Fool told Philippe about it, he received a kick that sent him flying across the flagstones. He had, nevertheless, uttered the word that was the key to his master’s destiny.

For Philippe of Valois, like every parvenu, was determined to show that he was worthy, by his own innate distinction, of the elevated position to which he had attained, and his behaviour therefore tended to an exaggeration of all that might be expected of a king.

Since the King exercised sovereign powers of justice, he sent the treasurer of the last reign to the gallows within three weeks of his accession. Pierre Rémy had been accused of embezzlement on a large scale. A Minister of Finance suspended from the gibbet was invariably popular with the crowd. France believed she had a just king.

By both duty and office the Prince was defender of the Faith. Philippe issued an edict increasing the penalties for blasphemy and enhancing the powers of the Inquisition. As a result, the higher and lower clergy, the minor nobility and the parish bigots were all reassured: they had a pious king.

A sovereign owed it to himself to recompense services rendered; and a great many services had been rendered Philippe to assure his election. On the other hand, the King must not make enemies of the officials who had been attentive to the public interest under his predecessors. As a result, nearly every dignitary or royal officer was retained in his position, while new posts were created or those already existing duplicated to find places for the supporters of the new reign. Every application put forward by the great electors was granted. Moreover, the Valois household, which was itself of royal proportions, was superimposed on that of the old dynasty; and there was a great distribution of profitable offices. They had a generous king.

A king was also in duty bound to bring his subjects prosperity. Philippe VI hastened to reduce and indeed in some cases to suppress altogether the taxes Philippe IV and Philippe V had imposed on trade, public markets and foreign business, taxes which it was said hindered enterprise and commerce.

And what could make a king more popular than to stop the plaguing by tax-gatherers? The Lombards, who had lent his father so much money and to whom he himself still owed enormous sums, blessed him. It occurred to no one that the fiscal policy of the previous reigns had produced long-term effects and that, if France was rich, if the standard of living was higher than anywhere else in the world, if the people wore good sound cloth and often fur and if there were baths and sweating-rooms even in hamlets, all these things were due to the previous Philippes, who had established order in the realm, the unification of the currency and full employment.

And then a king must also be wise, the wisest man among his people. Philippe began to adopt a sententious tone and, in that fine voice of his, to utter weighty aphorisms in which could be distinguished something of the manner of his old tutor, Archbishop Guillaume de Trye.

‘Action should always be based on reason,’ he would say whenever he was at a loss.

And when he made a mistake, which was often enough, and found himself in the unhappy position of having to countermand what he had ordered the day before, he would declare superbly: ‘Reason lies in developing one’s ideas.’ Or again: ‘It is better to be forearmed than forestalled,’ he would announce pompously, though throughout the twenty-two years of his reign he was to be constantly at the disadvantage of having to face one disagreeable surprise after another.

No monarch ever uttered so many platitudes with so grand an air. When people supposed he was thinking, he was in fact merely pondering a sentence that would seem like thought; his head was as empty as a nut in a bad season.

Nor was it to be forgotten that a king, a true king, must be valiant, chivalrous and gallant. And, indeed, Philippe had no aptitude for anything but arms – not for war, it must be admitted, but for jousts and tournaments. He would have excelled in training young knights at the Court of a minor baron. But, being a sovereign, his house began to look like a castle in the romances of the Round Table, which were much read at the time and had taken firm hold of his imagination. Life was a round of tournaments, festivals, banquets, hunts and entertainments, followed by more tournaments amid a flurry of plumed helms and horses more richly caparisoned than were the women.

Philippe applied himself with great devotion to affairs of State for an hour a day, either on his return, drenched with sweat, from jousting or on emerging from a banquet with a full stomach and a cloudy mind. His chancellor, his treasurer and his innumerable officers made his decisions for him or went to take orders from Robert of Artois. Indeed, Robert governed far more than the Sovereign.

No difficulty arose without Philippe appealing to Robert for advice, and the Count of Artois’ orders were obeyed with confidence, for it was known that any decree of his would be approved by the King.

This was how things stood, when the crowds began to gather towards the end of May for the coronation, at which Archbishop Guillaume de Trye was to place the crown on his former pupil’s head, and the festivities were to last for five days.

The whole kingdom seemed to have come to Reims; and not only the kingdom but a great part of Europe, for there were present the superb, if impecunious, King John of Bohemia, Count Guillaume of Hainaut, the Marquess of Namur, and the Duke of Lorraine. During the five days of feasting and rejoicing, there were a lavishness and an expenditure such as the burgesses of Reims had never seen before, and it was they who had to foot the bill for the festivities. Though they had grumbled at the cost of the previous coronation, they now gladly supplied two or three times as much. It was a hundred years since there had been such drinking in the Kingdom of France. There were even horsemen serving drinks in the courts and squares.

On the eve of the coronation, the King dubbed Louis of Nevers, Count of Flanders, knight with great pomp and ceremony. It had been decided that the Count of Flanders was to carry Charlemagne’s sword at the coronation and hand it to the King. The Constable, whose traditional privilege it was, had oddly enough consented to surrender it. But it was necessary that the Count of Flanders should be a knight; and Philippe VI could hardly have found a more signal means of showing his gratitude for the Count’s support.

Nevertheless, at the ceremony in the cathedral next day, when Louis of Bourbon, the Great Chamberlain of France, had shod the King with the lily-embroidered boots, and then proceeded to summon the Count of Flanders to present the sword, the Count made no move.

‘Monseigneur, the Count of Flanders!’ called Louis of Bourbon once again.

But Louis of Nevers stood still in his place with his arms crossed.

‘Monseigneur, the Count of Flanders,’ repeated the Duke of Bourbon, ‘if you be present, either in person or by representative, I call on you to come forward to fulfil your duty. You are hereby summoned to appear under pain of forfeiture.’