По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

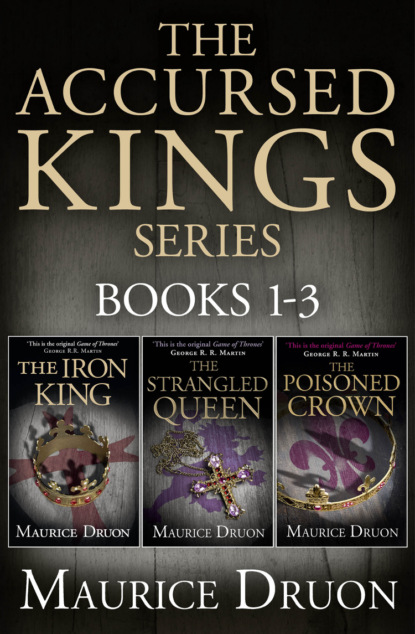

The Accursed Kings Series Books 1-3: The Iron King, The Strangled Queen, The Poisoned Crown

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I think that’s funny,’ said Louis of Navarre.

‘Be quiet, Louis,’ said the King, annoyed by their whispering.

To get rid of the uneasiness that was growing upon him, young Prince Charles compelled himself to think of something pleasant. He began to think of his wife Blanche, of Blanche’s wonderful smile, of Blanche’s body, of her tender arms soon to be stretched out to him, making him forget this horrible spectacle. How well she knew how to love him and spread happiness about her! If only their two children had not died when a few months old … But they would have others and then life would contain no single shadow. Enchantment and plenitude. Blanche had told him that tonight she was going to keep her cousin Marguerite company. But she would be home by now. Had she covered herself up well? Had she taken a sufficient escort?

The roaring of the crowd made him start. Flames were now leaping from the pyre. On an order from Alain de Pareilles, the archers extinguished their torches in the grass, and the night was now lit by the great brazier alone.

The flames reached the Preceptor of Normandy first. He made a pathetic movement of withdrawal as the tongues of fire licked at him, and his mouth opened wide as if he were trying vainly to breathe. In spite of the rope that bound him, his body bent almost double; his paper mitre fell off and the great white scar across his purple face became visible. The fire was all about him. Suddenly a pall of grey smoke engulfed him. When it had dissipated, Geoffroy de Charnay was in flames, screaming and gasping and trying to tear himself from the fatal stake which was shaken to its base. The Grand Master could be seen shouting something to him, but the crowd was growling so loudly in an attempt to drown its own horror, that it was impossible to hear what he said, except for the word ‘Brother’ twice repeated.

The assistant executioners were falling over each other in their haste to bring up reserves of wood and poke the fire with long iron prongs.

Louis of Navarre, whose mind always worked slowly, asked his brother, ‘Did you say that there was a light in the Tower of Nesle?’

For one moment he seemed disquieted.

Enguerrand de Marigny had placed a hand before his eyes as if to protect them from the light of the flames.

‘A fine vision of hell you’ve given us here, Nogaret!’ said Monseigneur of Valois. ‘Were you thinking of your future life?’

Guillaume de Nogaret did not reply.

The pyre had become a furnace and Geoffroy de Charnay was now no more than a blackened, sizzling object, swollen and blistered, slowly collapsing into the cinders, becoming cinder itself.

Women were fainting. Others were going quickly to the river bank to vomit into the channel, almost beneath the King’s nose. The crowd, after so much shouting, had grown calmer, and was beginning to talk about miracles because the wind obstinately contined blowing in the same direction and the flames had not yet reached the Grand Master.

How could he last so long? On his side the pyre seemed intact. Then, suddenly, the pyre caved in and the flames, reviving, leapt all about him.

‘That’s done for him too!’ cried Louis of Navarre.

With his long face and neck thrust forward, he was suddenly shaken by one of those incomprehensible gusts of laughter that always seized him at the most tragic moments.

Even at this spectacle Philip the Fair’s huge cold eyes were unblinking.

And suddenly the Grand Master’s voice sounded out of the curtain of fire. As if addressed to each one present, it affected everyone individually. With great power, his voice sounding as if it were already coming from on high, Jacques de Molay spoke again as he had done at Notre-Dame.

‘Shame! Shame! You are watching innocents die. Shame upon you! God will be your Judge.’

Flames whipped him, burning his beard, turning the paper hat in one second to ashes, setting his white hair alight.

The appalled crowd had fallen silent. It might have been a mad prophet who was being burned.

The Grand Master’s burning face was turned towards the royal loggia. And the terrible voice cried, ‘Pope Clement, Chevalier Guillaume de Nogaret, King Philip, I summon you to the Tribunal of Heaven before the year is out, to receive your just punishment! Accursed! Accursed! You shall be accursed to the thirteenth generation of your lines!’

The flames seemed to enter his mouth and stifle his last cry. And then, for what seemed an age, he fought against death.

At last he bent double. The cord broke. He fell forward into the furnace and only his hand remained raised among the flames. It stayed thus till it had turned entirely black.

Terrified by the curse, the crowd remained rooted to the spot. Nothing could be heard but sighs, murmurs of foreboding, consternation and anguish. The weight of the night and its horror seemed to lie over it; the shadows gradually gained ground against the dying light of the pyre.

The archers were trying to drive the crowd before them, but the people could not make up their minds to leave.

‘It wasn’t us whom he cursed; it was the King, wasn’t it?’ people were whispering.

People looked towards the loggia. The King was still standing by the balustrade. He was gazing at the Grand Master’s black hand sticking up out of the red embers. A burnt hand; all that remained of so much power and glory, all that remained of the illustrious Order of the Knights Templar. But the hand was motionless, raised in a gesture of imprecation.

‘Well, Brother,’ said Monseigneur of Valois with a nasty smile, ‘I suppose you’re happy now?’

Philip the Fair turned round.

‘No, Brother,’ he said. ‘I am not happy. I have committed an error.’

Valois was already preening himself, ready to enjoy his triumph.

‘Yes, I have committed an error,’ Philip repeated. ‘I ought to have had their tongues torn out before burning them.’

Still impassive, he left to return to his apartments, followed by Nogaret, Marigny and his Chamberlain.

The pyre had now turned grey, with here and there a spark of fire suddenly glowing only to die as quickly again. The loggia was full of smoke and a bitter stench of burning flesh.

‘It stinks,’ said Louis of Navarre. ‘I really think it stinks. Let’s go.’

Young Prince Charles was wondering whether even in Blanche’s arms he would manage to forget what he had seen.

9 (#ulink_a06fc733-1cbd-52f8-b67a-9afade0f9d6e)

The Cut-throats (#ulink_a06fc733-1cbd-52f8-b67a-9afade0f9d6e)

ON LEAVING THE TOWER OF NESLE, the brothers Aunay, walking to and fro in the mud, gazed into the darkness with some indecision.

Their ferryman had disappeared.

‘I told you I didn’t like the look of the fellow,’ said Gautier. ‘I ought to have acted on my suspicions.’

‘You gave him too much money,’ Philippe replied. ‘The scoundrel obviously thought he’d made enough for the day and went off to the execution.’

‘Let’s hope that’s all there is to it.’

‘What more could there be?’

‘I don’t know. But I don’t like the look of it. The fellow came and offered to take us over, pleading that he hadn’t earned a penny all day. We told him to wait; instead of doing so, he goes off.’

‘But what else could we have done? We had no choice; he was the only one there.’

‘Exactly,’ said Gautier. ‘And he asked rather too many questions.’

He stopped, listening for the sound of oars; but there was nothing but the rustling of the river and the widespread rumour from the crowd going back to their homes in Paris. Over there, upon the Island of Jews, which people from tomorrow would begin to call the Island of the Templars, the fire had gone out. A smell of smoke mingled with the dank stench of the Seine.

‘There’s nothing for it but to go home on foot,’ said Gautier. ‘We shall get muddy to the thighs. But after all it’s been worth it.’