По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

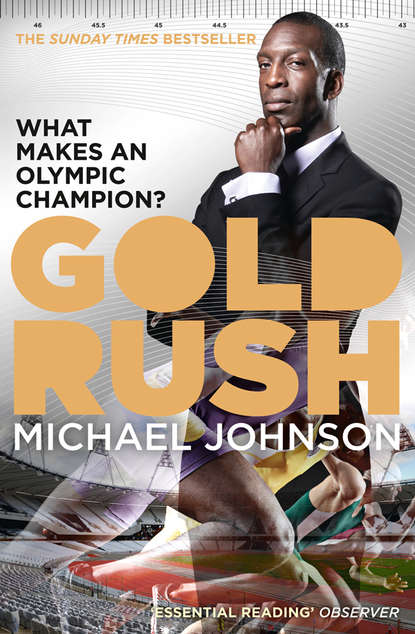

Gold Rush

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Just moments before the start of the Olympic 200 metres final, I couldn’t help but remind myself, ‘This is not just any other race. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I can win it and I can make history, but to do that I must run a mistake-free race.’ Deep into my focus, I thought about the things that I needed to do in the race along with those areas where I was most prone to making a mistake. I knew that Frankie and Ato, both being 100 metres specialists, were better starters than me. I also knew that a poor start induced by my thinking ahead to the 100-metre mark had caused me to lose to Frankie a couple of weeks earlier. Frankie had improved so much lately that I knew I would have to have a greater advantage over him at the halfway point of the race than I had in previous victories if I was going to beat him again.

While that was good knowledge to have before the race, I knew it was a mistake to be thinking ahead. You must take one stage of the race at a time and you must be focused only on the present stage of the race as opposed to two stages or even one stage ahead. Thinking about what I needed to be doing at the halfway mark meant that I wasn’t fully focused on the start and reacting to the gun. I vowed I would not repeat the mistake that had cost me a win just 14 days before.

After the introductions, which seemed to take forever, the starter finally called us to the starting blocks. At his cry of ‘On your marks’ I wanted to get into my blocks right away because I was ready to go. But that wasn’t my routine. I hated to be in position and have to wait for someone to finally start getting into theirs, so I always delayed a few seconds.

When I saw that everyone was getting into their blocks, I got into mine and waited. The starter announced, ‘Set!’ I rose to the set position and focused on the impending sound of the gun. Bang! I exploded out of the blocks.

My reaction time, 0.161 seconds, my best ever, was so good, I wasn’t ready for it. I drove my left foot off the rear block, pushed with my right foot on the front block and, with all of the force that I had, thrust my right arm forward and swung my left arm back, keeping my head down all through the first driving step out of the blocks. It went perfectly. Then everything switched and now I was pulling my right foot forward and pushing on the ground with my left foot and driving my left arm forward and swinging my right arm back with equal force as in the first stride. That all went perfectly as well.

Normally this process of driving out of the blocks with these steps goes on for at least ten steps. Ideally, the way the blocks are set up, during these ten steps your body is at a maximum 45-degree angle in relation to the track, which allows each step not to push down on the track but to push against the track, propelling your body forward with each push. In order to overcome gravity, a sprinter must utilise upper body strength and power and exaggerate the swing of the arms to prevent tripping and falling over.

I had shot out of the blocks so rapidly – probably due to a surge of adrenaline along with my intensified focus on the start – that my body bent at an angle deeper than the ideal 45 degrees. And my arm swing was not sufficient to keep up with the angle that I had achieved. That caught up with me on the third step. I was going back to my right foot driving forward, and my left foot had already made contact with the ground and I was starting to push with it. Just as I was switching over I felt my upper body start to fall over. To catch myself and stay upright, I had to shorten my right foot stride to hit the ground quicker than it should have.

I had allowed the moment and what I was about to do to take me out of my normal start which, while maybe not as great as some of the other sprinters, was good for me. I had just gotten the best start of my life, but I couldn’t handle a start that good. Focusing on the magnitude of the event and what was at stake, instead of executing the best I knew how, almost cost me Olympic gold and history. Fortunately one of the things that I was always good at and always prepared for is holding composure and getting over mistakes and moving on.

Mistakes are part of competing. You know that they will occur and you always try to minimise them, but when one happens during the race you must move on and determine quickly whether there is an adjustment to be made as a result of that mistake or if you continue with the same plan. I knew that having made a mistake you could not dwell on it or allow it to impact negatively on the rest of your race.

Luckily I had trained myself to deal with mistakes, so despite the stumble I was able to continue executing. I began making ground on the fast-starting Cuban, who I figured had left his best race in the semi-final in which he had come in second. I continued to drive and started to focus on Frankie Fredericks, two lanes outside of me. He was running well, but not making any ground on Ato Boldon, who was also running well.

I stopped thinking about them and focused back on my race, which was going excellently. At 60 metres into the race I was up on the Cuban and gaining on Frankie. I had already taken a lot out of the stagger, which meant that even though Frankie was still ahead of me I was winning the race because he had started ahead of me due to the staggered start. I was beginning to prepare for the transition from running the curve to running on the straight, which would happen at the 90 to 110 metres stage, the halfway point of the race. I was positioning myself so that during that transition I would start to gradually go from the inside to the outside of my lane. In addition to that small adjustment, I also started to gradually straighten up, since my left shoulder was slightly lower than my right as I leaned into the curve. When I came out of the curve I was far ahead of Frankie, Ato and the rest of the field.

At this point I knew I wouldn’t see any of the competition again. I also knew that I had won the race. Now it was all about maintaining form. Unlike the end of a 400-metre race, where you try to maintain form and fight against fatigue, in the last 100 metres of the 200 you try to run as fast as possible and maintain your technique, which is everything when it comes to efficiency and quickness. I was going well. Everything had been perfect except for that stumble. I reminded myself to run five metres past the finish line to ensure I didn’t slow down in trying to lean.

Five metres from the finish line I felt my hamstring go. Had the strain happened 20 metres earlier I wouldn’t have finished the race. But at this point I didn’t even slow down, even though it made the injury hurt worse. I only focused on the clock, which stopped at 19.32. Overjoyed, I threw my hands up in the air. ‘Yes!’ I screamed. I had shattered my old record of a month before. At the Olympic trials I had shaved 12 hundredths of a second off the record of 19.72 that had stood for 17 years. And now I had bettered that by just over a third of a second (34 hundredths to be exact). As the crowd screamed, with everyone on their feet and clapping, I continued to yell ‘Yes!’

As I walked back, Frankie came towards me smiling. I shook his hand and hugged him. Then Ato came over and started to bow down to me as he laughed. I hugged him and he congratulated me.

That’s when I finally grasped what had really just happened. I had completed the double. Relief, joy and elation swelled. Then I started to feel pain in my hamstring. It had been there since crossing the finish line, but the excitement had overridden the pain. I continued to ignore my leg. At that point I didn’t care if it fell off. I had won double Olympic gold!

2.

CATCHING OLYMPIC FEVER

I was an unlikely superstar. I was shy when I was growing up and used to get embarrassed very easily. My biggest fear was always – and to a lesser degree still is – the notion that everyone’s laughing at me but I don’t know it.

My older brother and three older sisters were the exact opposite, so they teased me a lot and embarrassed me even further by pointing out how I would do anything to avoid embarrassment. They thought that was pitiful. I didn’t care what they thought. I just knew that I didn’t like the feeling of being humiliated.

Unfortunately as a youngster that happened to me fairly consistently. When I was seven years old I had a friend named James who was the same age and lived two houses down from me. We played a lot, but whenever he didn’t like something that I did he would hit me. Each time that happened, I cried and slunk back to my house. When we moved to a new neighbourhood a year later, a kid named Keith, who was exactly like James, took over the role of friendly bully. We played together a lot, but it bothered him that I was better at sports than he was. So whenever he wanted to show me that he was better than me at something, he would want to fight me, because he knew I didn’t like to fight. So he would hit me. Once again, I would slink back home instead of retaliating.

My brother and sisters didn’t like that at all. Determined that I shouldn’t go on embarrassing the family by allowing myself to get beaten up, they tried to teach me how to fight. But I just didn’t like fighting. This went on for about three years. One day Keith took my bicycle and wouldn’t give it back. When he finally stopped and threw my bike down, I was so angry I punched him in the face. He tried to hit me back but I pushed him down and jumped on top of him and beat the crap out of him. ‘Don’t stop,’ yelled my brother and one of my sisters, who happened to be present at the time. ‘How many times has he hit you? Hit him back for every time.’ Eventually they pulled me off him and he ran home. After that we played together for years, without a single fight. I had evened the playing field and claimed my own sense of power. I felt good about myself after that and knew I would no longer have to live with that fear and embarrassment of not being able to take care of myself.

Although I could best Keith in sports, I wasn’t great in that department. Of course, that’s a relative statement. At the informal knockabout games at the park that defined my afternoons and weekends during elementary school, I’d get chosen first by my buddies for soccer and (American) football because of my speed. I was not as good at basketball. Not being considered one of the best didn’t sit well with me. So after finishing my homework or in the summers when school was out, I would take the basketball my grandfather had given me and go up to the court to practise shooting baskets. That was the only way I would learn to play better and get chosen first in that sport as well.

Even though I loved playing all sports, I loved experiencing the sensation of speed the most. I loved to run – and run fast. I would ride my bike fast. I had a skateboard and I would ride my skateboard fast. I would find a hill and ride my bike down the hill still pedalling fast, or I would run down the hill because I discovered that I could go faster if I was going downhill.

I was fast from the beginning. I think I first realised that I was fast at age six while playing with a few kids in my neighbourhood. About ten of us had decided to have a race at the park near my house. My friend Roderick who was also six was there, along with some older kids. One of them, Carlos, was my sister Deidre’s age, so he had to be about ten or eleven years old. We all lined up and we were running about 50 yards to a football goalpost. One kid called the start. He said, ‘On your marks, get set, go!’ and by the time he said go half the kids had already taken off. Even though I was late on the take-off, I managed to catch everyone, including the older kids, and won the race. ‘I didn’t even start on time, and I had to catch you all and I still won,’ I screamed to all the other kids. Of course, I had been playing sports with these kids for a while and always got to the ball first. So it was no surprise to anyone that day that I was fast – except me.

Even then, however, there was a difference between outrunning someone on the football field while trying to score a goal, or trying to prevent someone else from scoring a goal, and the lack of any subjectivity or complication in a foot race between me and others. The simple nature of a foot race was appealing to me. There was no skill or technique required at that point. It was simply a question of who was fastest. I wanted to be that person. And most times I was.

I was always very proud of winning. Every year in elementary school we had field day, a competition among all the kids in the school with events like the long jump and 50-yard dash. That was the only event I was really interested in and I won some blue ribbons. I remember one particular field day my mother had come up to the school to watch me participate. I won the race and looked over for her reaction. She was clapping and smiling as she nodded her head to me in approval. Having my mother there to watch me felt really good. I couldn’t wait to get home to hear her tell me how proud she was.

After school was over I ran home with my ribbon. I showed it to her as soon as I burst through the door. She looked at it, told me I had done a good job, then told me to get started on my homework and do my chores. That was the balance my parents showed. They were happy for me to participate in sports if it made me happy, but they never got carried away with it.

In addition to the school field days I also participated in a parks and recreation summer track programme called the Arco Jesse Owens Games. Every neighbourhood had a park, and in the summer kids from all the parks would come together and be grouped by age so they could compete against one another in different track and field events. I competed in the 50-yard dash and 100-yard dash. The first summer my sister Deidre and I participated in the Arco Jesse Owens Games, I had been the fastest in my age group at my park but finished in the middle of the pack at the Games. I didn’t like that feeling. I didn’t even know the other kids. I didn’t know if they were better than me. I just knew that I wanted to win and I had a strong belief that I could win. I told myself I would try harder the next time I had an opportunity to race. I honestly didn’t know what else I could do in the face of defeat.

Winning races had come easily to me up to that point. Looking back on that day, I think I was just so accustomed to winning the races I had run in my neighbourhood and at school that I expected to win. I knew I was fast and I liked the feeling of winning. I liked being good at something and I liked the attention I got from being fast.

Of course, I didn’t share that with anyone.

FAMOUS PERSONALITIES

‘If you look at most sportspeople – and this is the trend, not the absolute – they tend to be more introverts,’ says Sir Steven Redgrave, five-time gold medallist in rowing. ‘They tend to be more interested in what they’re doing – very quiet from that point of view.’

He speaks from personal experience. Like me, Steve was shy when he was growing up. ‘As a kid and even as a teenager, I wouldn’t say boo to a goose,’ he says. Heavily dyslexic, Steve, who had two older sisters, struggled with schoolwork. Sports – any kind of sports – became his outlet. ‘Even if I wasn’t that good at it, I still enjoyed doing it, because it was like freedom in some ways.’ So he played, in his words, ‘a little bit of football’ (or soccer for you American readers) for a team that was good enough to have a couple of its players go on to apprenticeships at professional clubs. ‘Little’ was the operative word since as reserve goalkeeper he sat on the side most of the time. He also ‘messed around’ with rugby week in and week out, playing on a team that needed volunteers from the football team to make up the 15 players required for a match. And as a competitive sprinter during junior school, he was one of the fastest in his home county of Buckinghamshire.

His sports escape routes broadened when the head of the school’s English department introduced Steve to rowing. ‘Our school was mainly a soccer school. Because he had a love for rowing, he used to go around and ask a few individuals if they’d like to give it a go. I hated school, so being asked to go out on the river in a games lesson once a week was a no-brainer from my point of view. The only problem is after two or three weeks we started going down every day after school. He asked 12 of us from my year. Within two weeks there were only four of us left that were committed to doing it.

‘He just made it so much fun. It wasn’t about maybe going to the Olympics or even racing anywhere; it didn’t even cross my mind. It was just about doing something a bit different that the other kids in my school didn’t get the opportunity to do.’

That first time out, Steve won seven out of seven races. Even though that gave him confidence, ‘I still wouldn’t have gone in town and told anybody,’ he says.

Daley Thompson may well be Steve’s polar opposite. A supremely confident athlete from the start, Daley made his mark in the 1980 Moscow Olympics by winning the decathlon, which consists of ten track and field events: 100 metres sprint, long jump, shot put, high jump, 400 metres sprint on the first day, and 110 metres hurdles, discus throw, pole vault, javelin throw and 1,500 metre race on day two. He then followed it up by successfully defending his title four years later in the 1984 Games. These Olympics were considered to be the Carl Lewis Games, because Lewis had established himself as the greatest track and field athlete since Jesse Owens. In fact, Carl was attempting to duplicate Jesse Owens’s amazing history-making moment from the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, when he won gold in the 100 metres, 200 metres, long jump and 4 x 100m relay. And Carl was attempting it in his home country during the Los Angeles Games. Daley, however, thought he was the better athlete and that the world should know. So he created a T-shirt, which he wore to the press conference after winning his second gold medal, which read: ‘Is the world’s second-greatest athlete gay?’

Although he later insisted that ‘gay’ meant ‘happy’ and that he hadn’t necessarily targeted Carl Lewis with the statement, the brash move created a firestorm. Fortunately, during his career his athletic performance was so superior that the sporting headlines outshone the others.

Daley was a very good athlete from the very beginning. He played football and found that he was superior athletically to the other kids. He would discover the same thing when he wandered down to the local track club a couple of times a week at the age of 15. He was so good that he actually made the British Olympic track team the following year and found himself competing at the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games on his birthday. ‘Day one of the decathlon was my birthday,’ he recalled. ‘I was 16 on the first day and 17 on the second day. I didn’t win that year, but just being on an Olympic team and having that Olympic experience was the most fun I ever had.’

Paralympian Tanni Grey-Thompson, who won a mind-boggling 16 Olympic medals including 11 golds, garnered a bronze medal during her first Olympic Games. She would go on to compete in four more Games, a feat as astonishing as her medal count.

‘I remember watching the 1984 Games on TV and thinking, “Wow, that would be really good to do that,”’ she told me. She had realised that she wanted to seriously compete in wheelchair racing several years earlier after participating in a race and coming in fourth. That proved to be a defining moment for her. ‘At that moment, everything else took second place,’ she recalls. Racing was exhilarating and fun. Not winning, however, was not. She says, ‘I remember thinking, I want to be better; I don’t want to come in fourth again.’

Over the next three years she continued to race competitively without making much of a mark. ‘In 1984 I wouldn’t have been on the radar of anybody,’ she says. ‘But as I watched the Games I thought, “I could do this if I worked really hard.”

‘I remember getting the letter saying I had made the 1988 Olympic team. I was at university and I’d come home for the Easter holidays. I came in through the front door on Saturday morning and my mum said to me, “There’s a letter there from the Paralympics Association.” I picked it up and looked at it, turned it over, and opened it. It said, “Dear Tanny, Congratulations.” I just screamed. My mum was like, “What? What?” I was hoping I’d make the team but I wasn’t expecting it. I’d made big improvements through 1987 and 1988 in terms of where I was in the world. But at 19 I was right on the borderline for going. So they took a real chance with me.’

Most people catch Olympic fever and work as hard as they can to earn a spot on the team. Daley’s success happened so fast that making the team provided him with the inspiration that would fuel him in the years that followed.

‘What was your first memory of the Olympics?’ I asked.

‘Watching Valeri Borzov on TV in the 1972 Olympics,’ he said. ‘I was really impressed with Borzov and how he carried himself.’ As Daley recalled, Valeri, a Russian 100-metre runner who was known as being a really tough competitor, ‘delivered a really great piece of work’.

As a two-time gold medal decathlete competing in ten different track and field events, Daley would go on to become the greatest athlete of his time. When I asked him about how he dealt with the pressure, he said, ‘I never felt pressure.’

I wouldn’t believe that from a lot of athletes, but I believe it with Daley. I don’t think he felt pressure, because where does the pressure come from? It comes from being afraid that you’re going to underperform – not necessarily compared to what other people expect but in terms of your own expectations. But Daley didn’t care. He just figured, ‘If I lose, I’m going to come back and I’m going to win the next time.’

Sprinter Usain Bolt says much the same thing. ‘People always say, “Why are you not worried?” I said you can’t be worried. If you’re the fastest man in the world, what’s there to worry about? Because you know you can beat them. All you’ve got to do is go execute,’ he told me when we talked in Jamaica in 2009. ‘I’m not saying every day you’re going to get it perfect, but if you’re fast there’s no need to worry. If you’ve had a bad day, you just had a bad day. Next time you bounce back.’

Despite his antics on the field, Usain isn’t exactly an extrovert. He prefers to chill at home or in his hotel room rather than to go out on the town. But when it comes to introverted champions, Cathy Freeman has us all beat.