По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

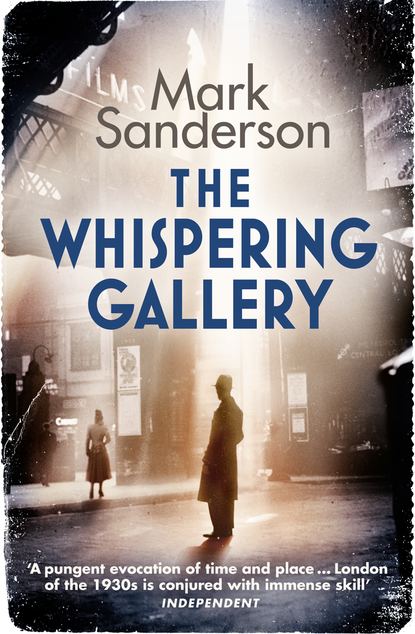

The Whispering Gallery

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“And you are . . .?”

“John Steadman, Daily News.”

“Ah.” The gimlet eyes bore into him. “Mr Yapp was a member of our chapter. I presume he’s beyond our help?”

“Indeed. My deepest condolences.”

The clergyman searched for but could not detect a note of insincerity. “I’m Father Gillespie, Deacon of St Paul’s.”

“How d’you do.” They shook hands. Johnny reached into his pocket and flipped open the notebook with its miniature pencil held in a tiny leather loop. It went everywhere with him. “What were Mr Yapp’s Christian names?”

“Graham and Basil. He was proud to share his initials with Great Britain.”

“Thank you. I don’t suppose you know who the other man is? It seems he jumped from the Whispering Gallery.”

“He wouldn’t be the first to have done so.” The deacon sighed and lowered his voice. “And doubtless won’t be the last.” The eavesdroppers craned their necks. “Ladies and gentlemen, please stand back. This is a house of God, not a freak show.”

“The police will have to be informed.”

“The call is being made as we speak.”

Johnny was impressed. “That was quick.” It wouldn’t take long for the Snow Hill mob to get here. He handed Father Gillespie a business card. “May I telephone you later?”

“Of course. But what’s the hurry? You’re an eyewitness. The police will want to talk to you.”

“Actually, I’m not. I didn’t see the man jump. For all I know, he could have been pushed. However, by all means tell the cops I was here. They know where to find me.”

The ring of spectators that was growing by the minute reluctantly parted to let him through. Forgetting, once again, where they were, they broke into an excited chatter. A look of exasperation flitted across Gillespie’s face. Would he have to close the cathedral?

Johnny, using shorthand, scribbled down a few details while they were still fresh in his memory – the exact location of the bodies, the appearance of the two corpses, their time of death – before hurrying down the north aisle and out of the door by All Souls Chapel.

It was like standing in front of a blast furnace. He squinted in the sunshine, blinded for a moment, then hurried down the steps which in the dazzling light appeared to be nothing more than a series of black-and-white parallel lines. It was so hot even the pigeons had sought the shade.

Should he wait for Stella or run with the story? He only hesitated for a moment. She was not expecting him to propose so would not be particularly disappointed. Besides, it would serve her right for being late yet again. She would guess what had happened when she saw the bloody aftermath where they were supposed to have rendezvoused.

As he made his way down Ludgate Hill, overtaking red-faced shoppers, he slipped off his jacket and slung it over his arm. He took off his hat and loosened his tie. It made little difference. Sweat trickled down his spine, made his shirt stick to the small of his back. He licked his top lip. He was glad the office was only five minutes away. He could see it in the distance, shimmering in the haze.

The newsroom was a sauna even though all the third-floor windows were flung wide open. The roar of traffic competed with the constant trilling of telephones and the machine-gun tat-a-tat of typewriters. Fans whirred uselessly on every desk. Any unanchored piece of paper would be sent waltzing to the floor. The sweet smell of ink from the presses on the ground floor and dozens of lit cigarettes failed to mask the odour of unwashed armpits.

Johnny checked his pigeonhole for any post, memos or telephone messages. There were several slips from the Hello Girls on the ground floor and two envelopes. Before he could open either of them, Gustav Patsel, the news editor, came waddling up to him.

“It is your day off, no? What are you doing here?”

Rumours that Patsel was going to jump ship – go to another newspaper, or goose-step back to his Fatherland – had so far proved annoyingly untrue. He made no secret of the fact that he disapproved of Johnny’s recent promotion from junior to fully fledged reporter, but hadn’t had the guts to say anything to the editor, Victor Stone. Like most bullies he had a yellow belly. Johnny’s previous position remained unfilled. The management, trying to slow the soaring overheads, had ordered a temporary freeze on recruitment.

“Pencil” – as Patsel was mockingly known – considered Johnny disrespectful. He could never tell when he was being serious or insubordinately facetious. However, Steadman was too good a journalist to sack. His exposé of corruption within the City of London Police the previous Christmas was still talked about. Patsel couldn’t afford to lose any more staff from the crime desk – Bill Fox had retired in March – and furthermore he didn’t want Johnny working for the competition.

“I’ve got a story and I guarantee you no one else has got it – yet. A man’s just committed suicide in St Paul’s.”

“So what? Cowards kill themselves every day.”

“Only someone who doesn’t understand depression and despair would say that,” said Johnny, bristling. He held up his hand to stop the inevitable torrent of spluttering denial. “There’s more: he took someone with him. When he jumped from the Whispering Gallery he landed on a priest.”

“Ha!” The single syllable expressed both laughter and relief. Patsel’s eyes glittered behind the round, wire-rimmed glasses. “So much for the power of the Saviour. Has he been identified?”

“I know who the priest was, but the jumper didn’t have anything on him except his clothes. No money, no note, no photograph.”

“How do you know this?”

“I was there. I went through his pockets.”

Patsel was impressed – but he wasn’t about to show it.

“What?” Johnny could tell his boss was itching to say something.

“It is not important. Okay. Give me three hundred words – and try to get a name for the suicide.”

Johnny nodded. He had an hour and a half to develop the lead into a proper story. The copy deadline for the final edition was 5 p.m. There was a sports extra on a Saturday so that most of the match results could be included. He flopped down into Bill’s old chair and tipped back as far as he could go, just as his mentor had. Fox had taught him a great deal – in and out of the office. Although Johnny had no intention of following in the footsteps of the venal but essentially good-hearted hack, he had taken his desk when he left. It was by a window – not that it offered much of a view beyond the rain-streaked sooty tiles and rusting drainpipes in the light well at the core of the building.

“Stood you up, did she?” Louis Dimeo, the paper’s sports reporter, had slipped into the vacant seat at the desk opposite, which used to be Johnny’s. A grin lit up his dark, Italian features. Johnny was handsome enough but Louis, who spent most of his spare time kicking a ball or kissing girls, was in a different league – as he never stopped reminding him.

“Who?”

“Seeing more than one woman, are we? Surely you haven’t taken a leaf out of my book? Stella, of course.” They sometimes had a drink together after work – always with other colleagues, never alone – but Louis was too concerned about his physique to sink more than a couple of pints.

“An exclusive fell into my lap. Well, almost.” His telephone started ringing. “Haven’t you got anything better to do?”

“It’s all under control. The stringers will soon be calling the copytakers.”

“Why aren’t you at a match?”

“I drew the short straw. Answer the bloody thing!” He sloped off back to his own desk.

“Steadman speaking.”

“You must know by now that leaving the scene of a crime is against the law.”

“So is suicide, but there’s not much you can do about it, is there?” He smiled. It was always good to hear from Matt.

“What did she say?”

“I haven’t asked her. She hadn’t turned up by the time I left. She was late, as usual.”

“Constable Watkiss tells me you spoke to Father Gillespie. As you’re no doubt aware, the man who jumped had no identification on him. We’ll be releasing an artist’s impression of him on Monday – if his wife hasn’t reported him missing by then.”

“How d’you know he was married? He wasn’t wearing a ring.”

“We don’t. I’m just hazarding a guess. His appearance doesn’t match that of anyone on our missing-persons list.”