По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

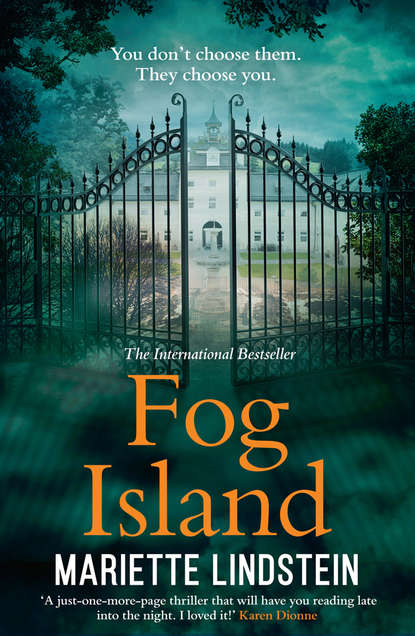

Fog Island: A terrifying thriller set in a modern-day cult

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Her hope of sneaking back to her warm bed was immediately extinguished. This didn’t look good. At all.

Bosse divided them into groups that were to work on different parts of the renovation. She ended up in the painting group along with Elvira.

And so began the craziest, most chaotic and sleepless period in her life thus far. Days and nights flowed together into the sort of mishmash that can only arise from a large group of people who have no plan or idea what to do. They sawed, swept, polished, sandpapered, and painted. Bosse and his new henchmen ran around trying to make everyone move faster by shouting things like ‘Faster!’ and ‘You have fifteen minutes to finish that!’ and since all these commands were perfectly meaningless, no one listened.

They slept for a few hours each night; sometimes not even that much. After several sleepless nights, staff were dozing off here and there and had to be shaken into consciousness to get going again.

Sofia tried to stay awake as best she could. She painted and painted. Her hands, arms, legs, feet, and hair were covered in white paint.

What have I gotten myself into? What am I doing here?

The thought returned to her daily, but she kept painting with Elvira. They became friends there among the cans, brushes, and turpentine. They shared water bottles and gum. They kept watch for each other when one slipped into the storage room to take a nap on the hard floor behind the shelves, when they simply couldn’t manage any longer. If someone in the leader group, as they called Bosse’s gang, headed for the storage room, all the person keeping watch could do was rush over and distract them. She would cough three times to wake the sleeper, to give her time to rub the sleep from her eyes. That was all it took — it was impossible to sleep deeply on the ice-cold floor. The three coughs broke through slumber like it was the first thin layer of ice on a pond; the alert brought the sleeper to her feet and she would dart out of the storeroom and go right back to painting.

Each time it seemed they were done, something else popped up. The wrong colour paint somewhere; baseboards that weren’t high enough; mismatched furniture. And every time something went wrong, the group experienced new, greater levels of hysteria and frenzy.

She was swallowed by exhaustion; it got worse each day. Her eyelids were leaden and the brush felt huge in her hand.

But she gritted her teeth and kept painting.

Then one day, all of a sudden, they were finished.

They looked at each other in wonder, dumbfounded, almost positive that it couldn’t be true. There had to be something else that needed fixing. But after several checks, the leader group determined that the job was done.

They hadn’t seen Oswald a single time since that horrible night in the rain, but now he had to be called to inspect their work.

He made them wait for two days. They spent the time cleaning and polishing, moving furniture back and forth, burnishing door handles. They didn’t dare leave the floor out of fear that he might suddenly show up.

When he arrived, he walked around the rooms three times.

He didn’t utter a word. At last he nodded.

The nightmare was over.

*

Oswald allowed them to celebrate with a party in the dining room. Food, wine, music, and dancing — it was like stepping into a new world. He attended the party too. He spoke with the staff, joking, laughing, and back-slapping.

When he caught sight of Sofia, he made a sort of apology.

‘I know you’re new here,’ he said. ‘But sometimes it’s necessary to take off the kid gloves. I’m sure you understand.’

‘Of course!’ she said cheerfully, hoping he wouldn’t notice the white paint she hadn’t been able to get out of her hair.

But his fingers took hold of a matted clump near her cheek, then slid down her face to the tip of her chin.

‘Look how hard you’ve been working! Sofia, I’m so glad to have you here.’

A jolt zinged from her cheek to her groin. She tried to keep a poker face and shrugged. But he noticed. He gave her a meaningful smile and raised his eyebrows before moving on.

She was still feeling drained from the lack of sleep and couldn’t quite let herself sink into the joyful mood. She kept thinking about how her dorm room was empty and she could sneak off, pull out her laptop, and send an email home. Make contact after two weeks of silence.

The party music was loud, throbbing. The sounds of renovation, blows of the hammer and the whine of the circular saw were still echoing through her head. She decided to make herself invisible and sneak out the front door.

That’s where she ran into him.

He must have been coming from outside, because he brought with him a gust of cold autumn wind and the scent of leather from his jacket. His eyes were just as she recalled, happy and lively. The wind had blown his hair back, making it look like a funny toupee. His mouth was half open, revealing the gap between his front teeth.

‘God, I’m so glad you’re here!’ he said, taking her hands. Suddenly she wasn’t tired in the least.

A few weeks have passed since I found the book.

A thought has been with me ever since.

It’s insane and dizzying, but genius.

I’ve been snooping for more evidence hidden away by my idiotic mother — she thinks she’s so clever.

At the moment she’s sitting at the kitchen table, gazing out the window. Grumpy and grim. Her jaw is clenched as if she has taken a vow of eternal silence. I sit down on the chair across from her.

‘I hate you more than anyone else ever could,’ I say.

She doesn’t say ‘Oh, no!’ or ‘You can’t say that!’ or anything a normal mother would have said.

She just sits there staring, stiff and silent as a dead fish. And it’s all her fault — especially the fact that we’re sitting here in a fucking summer cottage, poor and insignificant. All because she had to have a quickie with the count. And yet, to my great chagrin, I see myself in her as she sits there.

We are strong, bull-headed, stubborn. There is not a pitiful bone in our bodies.

Not like that cowardly bastard who fled the island for some stupid place in France.

No, I know that I take after her, and that makes me hate her even more.

‘I wrote to him,’ I say, holding the letter up for her to see. Close enoughfor her to read the name on the envelope. At last her eyes go cloudy with worry and she opens her mouth to say something.

But I’m already on my way out of the cottage.

When I turn around on the lawn, I see that she has stood up and come to the window.

Go ahead and stare, I think. Stare all you want — but it’s too late.

10 (#ulink_2aaaea50-2da8-54b4-babc-a097e5a5565c)

The fog took hold of the island in early October, and by mid-month it had an iron grip on the place. It crept in at night and each morning it was so thick that Sofia couldn’t see the outbuildings from the window in her dormitory. The brightly coloured leaves had faded and the landscape had turned shades of golden-brown. It was steadily growing colder. Normally she would have felt a little gloomy thanks to all the fog. But not now — she spent almost all her time thinking about Benjamin. It was as if the fog transformed the island into a fairy-tale world with infinite curtains a person could pass through and discover fresh views.

Benjamin showed up in the library every day. She never knew when he would appear, so she remained in a state of constant expectation and excitement. He always had a good excuse to visit. Oswald had instructed him to help with all the purchasing. But most of the time he came by with trivial questions and errands. He had that eager way about him as if he were always on the go. He could fill an entire room with his energy just by stepping across the threshold. He would forget to remove his boots, tramping around and leaving marks on the rugs without noticing. His body was always in motion — he walked around looking out of windows, picking up objects, putting them down again — even as he spoke with her. But when he sat down in front of her he became perfectly still. He could move in and out of these states, from wound up to absolutely relaxed, in an instant.

She had a constant internal dialogue about whether it was right to start a new relationship so soon after the disaster with Ellis; her brain went back and forth, over and over. This nervous droning was like background music as she worked. But when Benjamin entered the room, the voices stopped. And then it started up again until Sunday, when he showed her the cave.

It was their day off and the whole island was blanketed in a thick fog. Everything was wet: the trees, the bushes, and the earth, which smelled like mushrooms and decaying leaves. He showed her a new path through the woods; they had to climb over huge, moss-covered stones to move forward.