По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

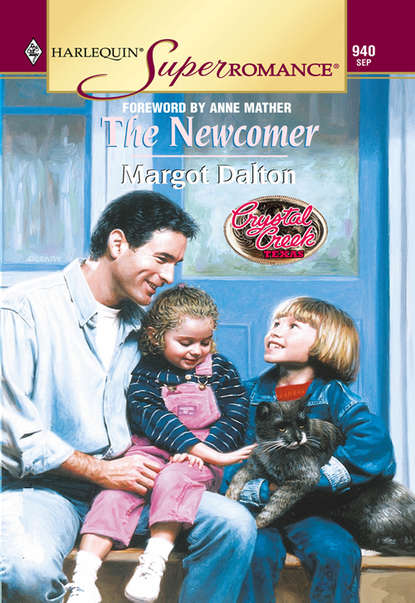

The Newcomer

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

THE CAROUSEL HORSES stood frozen in the misty chill of the February afternoon. Silver hooves pawed silently at the floorboards, dark eyes rolled wildly, while manes and tails streamed as if blown by the wind. A fitful sun broke through dark clouds above the hills, sparked fire from gold-mounted saddles and jeweled breastplates.

Lovingly, Douglas Evans caressed the blond mane of a fiery sorrel with bared yellow teeth, then knelt to examine a splintered board on the floor near the big tiger, whose jaws were drawn back in a menacing snarl.

The tiger had been discovered wrapped under layers of oilcloth in June Pollock’s cellar, more than sixty years after the dismantling of the Crystal Creek carousel. Unlike many of the other animals, this one had hardly needed any restoration. Its broad striped back was worn smooth from the thousands of tiny riders who’d sat on him, wide-eyed and awed at their own daring, as the tiger paced slowly around the carousel platform.

“Unca Dougie,” a small voice called from somewhere outside the carousel enclosure. “I’m cold.”

“Put your brush down, Robin, and come up here,” Doug said.

His rich Scottish brogue sounded loud and a little intrusive, even to his own ears, on this silent winter afternoon in the Hill Country of central Texas.

He smiled as his niece plodded up the carousel steps and tumbled at his feet in a bright plaid jacket and hood. She lay on her back and waved her green running shoes in the air.

Robin was four years old, a plump, happy little girl with golden curls, red cheeks and an irrepressible personality, as different from her older sister Moira as two children could possibly be. Doug loved his young nieces as if they were his own children, and spent a good deal of time worrying about them.

Especially nowadays…

Hiding his frown of concern, he bent and lifted Robin into his arms. Then he sat on the bench next to the tiger and cuddled the child, making a great show of putting his big hands over her ears and rubbing her cold cheeks.

She squirmed and giggled, forgetting her complaints, then settled contentedly against his denim jacket and looked around at the carousel. With a surreptitious glance at her uncle, Robin jammed her thumb in her mouth and began sucking it thoughtfully.

Doug gently removed the thumb and kissed her bright hair. She made no objection, just nestled more cozily in his arms.

“Tell me again about all the horses and stuff,” she commanded.

Doug settled back and extended his long legs in blue jeans and heavy work boots.

“Well, this carousel is the most wonderful thing,” he told the little girl, his burr becoming more pronounced, as it always did when he told stories to his nieces. “And the animals are verra, verra old.”

“How old?”

“Almost a hundred years.”

“Older than Mummy, then.”

Doug chuckled. “Yes, my sweetheart, much older than Mummy. These fifty-four horses, and the lion and tiger and giraffe were hand-carved, every single one of them, by a man called Franz Koning who lived in Germany. For many years the carousel was one of this town’s proudest possessions. But in the Great Depression, Crystal Creek lost its carousel,” he said sadly.

Robin frowned with anxiety, which she always did at this point in her uncle’s story.

“What happened?”

Doug cuddled the child, and reached over to stroke the tiger’s glossy head. “It was broken up and sold, piece by piece, to the highest bidders. The horses and all these other animals were scattered all over the world.”

“How did they get back here, Unca?”

“A very rich, very kind man found all the parts of the carousel, and paid a lot of money to have them restored to their former glory. Then he presented them as a gift to the town of Crystal Creek. This carousel is a symbol, my chickie.”

Doug nuzzled her hair again. Robin was warm and heavy in his arms; he could tell she was getting sleepy.

“Symbol?” she asked, her eyelids fluttering drowsily.

“It stands for the pride of the town.” Doug looked with satisfaction at the bright carousel in its enclosure on the lawn in front of the courthouse. “This is the jewel in our lapel, my darling. It shows that Crystal Creek has pride in itself and its history, and will always be a fine town to live in.”

But Robin was asleep by now, slumping against his chest.

Carefully Doug made a nest for her on the bench, using his jacket to wrap her against the chill and taking care to cover her little shoes with the sheepskin-lined denim.

He bent to kiss her again, then went down the steps and around a corner to find his older niece working doggedly, applying a coat of green stain to the lower portion of the carousel enclosure beneath tall Plexiglas windows.

Doug looked with fondness at the child.

Moira was nine years old, a timid, serious little girl with big gray eyes, straight blond hair cut in a Dutch bob and a thin body in blue jeans and a parka.

The girl had a quaintly old-fashioned air about her, as if she should be sitting in some Victorian nursery, dressed in a pinafore and buttoned boots, doing her sums and letters on a slate. Moira was always quiet and self-contained, with little of the pushing or shouting common to most children her age, and none of her younger sister’s cheerful ebullience.

Poor Moira carried the weight of the world on her shoulders, Doug thought with sympathy, picking up a brush to join her. And narrow, fragile shoulders they were, too.

“Robin fell asleep,” he reported.

“Where is she?” Moira looked around in concern. Taking care of her impulsive younger sister was one of her responsibilities.

He gestured over his shoulder. “She’s curled up on the bench next to the tiger.”

“Is she warm enough?” Frowning, Moira dipped her brush carefully and squeezed excess stain onto the edge of the bucket.

Doug chuckled and reached out to touch his niece’s shining cap of hair.

“Nine years old, but going on twenty-nine, you are,” he said teasingly. “Take care of us all, don’t you, Pumpkin?”

She smiled a little, then drew back tactfully from his hand. Unlike her sister, Moira disliked being touched or cuddled.

They worked in silence for a while. Doug, always sensitive to her moods, could tell something was bothering the child.

“So, Moira.” He carried the pail of stain around on the grass and knelt to paint a new section. “What is it, then?”

She looked away from him, biting her lip. Doug studied the vulnerable line of his niece’s neck, the pale curve of her little freckled cheek.

“Mummy cried last night,” she said at last, her face still averted.

Doug’s heart sank but he kept his voice deliberately casual. “Did she, now?”

Moira nodded, concentrating on painting a lower row of boards with extreme care.

“Well,” Doug said with false heartiness, “as I understand it, ladies cry quite often. When they’re upset, it makes them feel better.”