The Fair God; or, The Last of the 'Tzins

“But honor, father,—”

“That will come by waiting.”

“Alas!” said the ’tzin, bitterly, “I have waited too long already. I have most dismal news. When Malinche marched to Cempoalla, he left in command here the red-haired chief whom we call Tonatiah. This, you know, is the day of the incensing of Huitzil’—”

“I know, my son,—an awful day! The day of cruel sacrifice, itself a defiance of Quetzal’.”

“What!” said Guatamozin, in angry surprise. “Are you not an Aztec?”

“Yes, an Aztec, and a lover of his god, the true god, whose return he knows to be near, and,”—to gather energy of expression, he paused, then raised his hands as if flinging the words to a listener overhead,—“and whom he would welcome, though the land be swimming in the blood of unbelievers.”

The violence and incoherency astonished the ’tzin, and as he looked at the paba fixedly, he was sensible for the first time of a fear that the good man’s mind was affected. And he considered his age and habits, his days and years spent in a great, cavernous house, without amusement, without companionship, without varied occupation; for the thinker, it must be remembered, knew nothing of Tecetl or the world she made so delightful. Moreover, was not mania the effect of long brooding over wrongs, actual or imaginary? Or, to put the thought in another form, how natural that the solitary watcher of decay, where of all places decay is most affecting, midst antique and templed splendor, should make the cause of Quetzal’ his, until, at last, as the one idea of his being, it mastered him so absolutely that a division of his love was no longer possible. If the misgiving had come alone, the pain that wrung the ’tzin would have resolved itself in pity for the victim, so old, so faithful, so passionate; but a dreadful consequence at once presented itself. By a strange fatality, the mystic had been taken into the royal councils, where, from force of faith, he had gained faith. Now,—and this was the dread,—what if he had cast the glamour of his mind over the king’s, and superinduced a policy which had for object and end the peaceable transfer of the nation to the strangers?

This thought thrilled the ’tzin indefinably, and in a moment his pity changed to deep distrust. To master himself, he walked away; coming back, he said quietly, “The day you pray for has come; rejoice, if you can.”

“I do not understand you,” said Mualox.

“I will explain. This is the day of the incensing of Huitzil’, which, you know, has been celebrated for ages as a festival religious and national. This morning, as customary, lords and priests, personages the noblest and most venerated, assembled in the court-yard of the temples. To bring the great wrong out in clearer view, I ought to say, father, that permission to celebrate had been asked of Tonatiah, and given,—to such a depth have we fallen! And, as if to plunge us into a yet lower deep, he forbade the king’s attendance, and said to the teotuctli, ‘There shall be no sacrifice.’”

“No victims, no blood!” cried Mualox, clasping his hands. “Blessed be Quetzal’!”

The ’tzin bore the interruption, though with an effort.

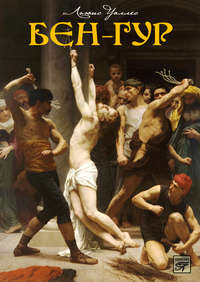

“In the midst of the service,” he continued, “when the yard was most crowded, and the revelry gayest, and the good company most happy and unsuspecting, dancing, singing, feasting, suddenly Tonatiah and his people rushed upon them, and began to kill, and stayed not their hands until, of all the revellers, not one was left alive; leaders in battle, ministers at the altar, old and young,—all were slain!47 O such a piteous sight! The court is a pool of blood. Who will restore the flower this day torn from the nation? O holy gods, what have we done to merit such calamity?”

Mualox listened, his hands still clasped.

“Not one left alive! Not one, did you say?”

“Not one.”

The paba arose from his stooping, and upon the ’tzin flashed the old magnetic flame.

“What have you done, ask you? Sinned against the true and only god—”

“I?” said the ’tzin, for the moment shrinking.

“The nation,—the nation, blind to its crimes, no less blind to the beginning of its punishment! What you call calamity, I call vengeance. Starting in the house of Huitzil’,—the god for whom my god was forsaken,—it will next go to the city; and if the lords so perish, how may the people escape? Let them tremble! He is come, he is come! I knew him afar, I know him here. I heard his step in the valley, I see his hand in the court. Rejoice, O ’tzin! He has drunk the blood of the sacrificers. To-morrow his house must be made ready to receive him. Go not away! Stay, and help me! I am old. Of the treasure below I might make use to buy help; but such preparation, like an offering at the altar, is most acceptable when induced by love. Love for love. So said Quetzal’ in the beginning; so he says now.”

“Let me be sure I understand you, father. What do you offer me?” asked the ’tzin, quietly.

“Escape from the wrath,” replied Mualox.

“And what is required of me?”

“To stay here, and, with me, serve his altar.”

“Is the king also to be saved?”

“Surely; he is already a servant of the god’s.”

Under his gown the ’tzin’s heart beat quicker, for the question and answer were close upon the fear newly come to him, as I have said; yet, to leave the point unguarded in the paba’s mind, he asked,—

“And the people: if I become what you ask, will they be saved?”

“No. They have forgotten Quetzal’ utterly.”

“When the king became your fellow-servant, father, made he no terms for his dependants, for the nation, for his family?”

“None.”

Guatamozin dropped the hood upon his shoulders, and looked at Mualox sternly and steadily; and between them ensued one of those struggles of spirit against spirit in which glances are as glittering swords, and the will holds the place of skill.

“Father,” he said, at length, “I have been accustomed to love and obey you. I thought you good and wise, and conversant with things divine, and that one so faithful to his god must be as faithful to his country; for to me, love of one is love of the other. But now I know you better. You tell me that Quetzal’ has come, and for vengeance; and that, in the fire of his wrath, the nation will be destroyed; yet you exult, and endeavor to speed the day by prayer. And now, too, I understand the destiny you had in store for me. By hiding in this gown, and becoming a priest at your altar, I was to escape the universal death. What the king did, I was to do. Hear me now: I cut myself loose from you. With my own eyes I look into the future. I spurn the destiny, and for myself will carve out a better one by saving or perishing with my race. No more waiting on others! no more weakness! I will go hence and strike—”

“Whom?” asked Mualox, impulsively. “The king and the god?”

“He is not my god,” said the ’tzin, interrupting him in turn. “The enemy of my race is my enemy, whether he be king or god. As for Montezuma,”—at the name his voice and manner changed,—“I will go humbly, and, from the dust into which he flung them, pick up his royal duties. Alas! no other can. Cuitlahua is a prisoner; so is Cacama; and in the court-yard yonder, cold in death, lie the lords who might with them contest the crown and its tribulations. I alone am left. And as to Quetzal’,—I accept the doom of my country,—into the heart of his divinity I cast my spear! So, farewell, father. As a faithful servant, you cannot bless whom your god has cursed. With you, however, be all the peace and safety that abide here. Farewell.”

“Go not, go not!” cried Mualox, as the ’tzin, calling to Hualpa, turned his back upon him. “We have been as father and son. I am old. See how sorrow shakes these hands, stretched toward you in love.”

Seeing the appeal was vain, the paba stepped forward and caught the ’tzin’s arm, and said, “I pray you stay,—stay. The destiny follows Quetzal’, and is close at hand, and brings in its arms the throne.”

Neither the tempter nor the temptation moved the ’tzin; he called Hualpa again; then the holy man let go his arm, and said, sadly, “Go thy way,—one scoffer more! Or, if you stay, hear of what the god will accuse you, so that, when your calamity comes, as come it will, you may not accuse him.”

“I will hear.”

“Know, then, O ’tzin, that Quetzal’, the day he landed from Tlapallan, took you in his care; a little later, he caused you to be sent into exile—”

“Your god did that!” exclaimed the ’tzin. “And why?”

“Out of the city there was safety,” replied Mualox, sententiously; in a moment, he continued, “Such, I say, was the beginning. Attend to what has followed. After Montezuma went to dwell with the strangers, the king of Tezcuco revolted, and drew after him the lords of Iztapalapan, Tlacopan, and others; to-day they are prisoners, while you are free. Next, aided by Tlalac, you planned the rescue of the king by force in the teocallis; for that offence the officers hunted you, and have not given over their quest; but the cells of Quetzal’ are deep and dark; I called you in, and yet you are safe. To-day Quetzal’ appeared amongst the celebrants, and to-night there is mourning throughout the valley, and the city groans under the bloody sorrow; still you are safe. A few days ago, in the old palace of Axaya’, the king assembled his lords, and there he and they became the avowed subjects of a new king, Malinche’s master; since that the people, in their ignorance, have rung the heavens with their curses. You alone escaped that bond; so that, if Montezuma were to join his fathers, asleep in Chapultepec, whom would soldier, priest, and citizen call to the throne? Of the nobles living, how many are free to be king? And of all the empire, how many are there of whom I might say, ‘He forgot not Quetzal’’? One only. And now, O son, ask you of what you will be accused, if you abandon this house and its god? or what will be forfeit, if now you turn your back upon them? Is there a measure for the iniquity of ingratitude? If you go hence for any purpose of war, remember Quetzal’ neither forgets nor forgives; better that you had never been born.”

By this time, Hualpa had joined the party. Resting his hand upon the young man’s shoulder, the ’tzin fixed on Mualox a look severe and steady as his own, and replied,—“Father, a man knows not himself; still less knows he other men; if so, how should I know a being so great as you claim your god to be? Heretofore, I have been contented to see Quetzal’ as you have painted him,—a fair-faced, gentle, loving deity, to whom human sacrifice was especially abhorrent; but what shall I say of him whom you have now given me to study? If he neither forgets nor forgives, wherein is he better than the gods of Mictlan? Hating, as you have said, the sacrifice of one man, he now proposes, you say, not as a process of ages, but at once, by a blow or a breath, to slay a nation numbering millions. When was Huitzil’ so awfully worshipped? He will spare the king, you further say, because he has become his servant; and I can find grace by a like submission. Father,”—and as he spoke the ’tzin’s manner became inexpressibly noble,—“father, who of choice would live to be the last of his race? The destiny brings me a crown: tell me, when your god has glutted himself, where shall I find subjects? Comes he in person or by representative? Am I to be his crowned slave or Malinche’s? Once for all, let Quetzal’ enlarge his doom; it is sweeter than what you call his love. I will go fight; and, if the gods of my fathers—in this hour become dearer and holier than ever—so decree, will die with my people. Again, father, farewell.”

Again the withered hands arose tremulously, and a look of exceeding anguish came to the paba’s help.

“If not for love of me, or of self, or of Quetzal’, then for love of woman, stay.”

Guatamozin turned quickly. “What of her?”

“O ’tzin, the destiny you put aside is hers no less than yours.”

The ’tzin raised higher his princely head, and answered, smiling joyously,—

“Then, father, by whatever charm, or incantation, or virtue of prayer you possess, hasten the destiny,—hasten it, I conjure you. A tomb would be a palace with her, a palace would be a tomb without her.”

And with the smile still upon his face, and the resolution yet in his heart, he again, and for the last time, turned his back upon Mualox.

CHAPTER V

THE CELLS OF QUETZAL’ AGAIN

“A victim! A victim!”

“Hi, hi!”

“Catch him!”

“Stone him!”

“Kill him!”

So cried a mob, at the time in furious motion up the beautiful street. Numbering hundreds already, it increased momentarily, and howled as only such a monster can. Scarce eighty yards in front ran its game,—Orteguilla, the page.

The boy was in desperate strait. His bonnet, secured by a braid, danced behind him; his short cloak, of purple velvet, a little faded, fluttered as if struggling to burst the throat-loop; his hands were clenched; his face pale with fear and labor. He ran with all his might, often looking back; and as his course was up the street, the old palace of Axaya’ must have been the goal he sought,—a long, long way off for one unused to such exertion and so fiercely pressed. At every backward glance, he cried, in agony of terror, “Help me, O Mother of Christ! By God’s love, help me!” The enemy was gaining upon him.

The lad, as I think I have before remarked, had been detailed by Cortes to attend Montezuma, with whom, as he was handsome and witty, and had soon acquired the Aztecan tongue and uncommon skill at totoloque, he had become an accepted favorite; so that, while useful to the monarch as a servant, he was no less useful to the Christian as a detective. In the course of his service, he had been frequently intrusted with his royal master’s signet, the very highest mark of confidence. Every day he executed errands in the tianguez, and sometimes in even remoter quarters of the city. As a consequence he had come to be quite well known, and to this day nothing harmful or menacing had befallen him, although, as was not hard to discern, the people would have been better satisfied had Maxtla been charged with such duties.

On this occasion,—the day after the interview between the ’tzin and Mualox,—while executing some trifling commission in the market, he became conscious of a change in the demeanor of those whom he met; of courtesies, there were none; he was not once saluted; even the jewellers with whom he dealt viewed him coldly, and asked not a word about the king; yet, unaware of danger, he went to the portico of the Chalcan, and sat awhile, enjoying the shade and the fountain, and listening to the noisy commerce without.

Presently, he heard a din of conchs and attabals, the martial music of the Aztecs. Somewhat startled, and half hidden by the curtains, he looked out, and beheld, coming from the direction of the king’s palace, a procession bearing ensigns and banners of all shapes, designs, and colors.

At the first sound of the music, the people, of whom, as usual, there were great numbers in the tianguez, quitted their occupations, and ran to meet the spectacle, which, without halting, came swiftly down to the Chalcan’s; so that there passed within a few feet of the adventurous page a procession rarely beautiful,—a procession of warriors marching in deep files, each one helmeted, and with a shield at his back, and a banner in his hand,—an army with banners.

At the head, apart from the others, strode a chief whom all eyes followed. Even Orteguilla was impressed with his appearance. He wore a tunic of very brilliant feather-work, the skirt of which fell almost to his knees; from the skirt to the ankles his lower limbs were bare; around the ankles, over the thongs of the sandals, were rings of furbished silver; on his left arm he carried a shield of shining metal, probably brass, its rim fringed with locks of flowing hair, and in the centre the device of an owl, snow-white, and wrought of the plumage of the bird; over his temples, fixed firmly in the golden head-band, there were wings of a parrot, green as emerald, and half spread. He exceeded his followers in stature, which appeared the greater by reason of the long Chinantlan spear in his right hand, used as a staff. To the whole was added an air severely grand; for, as he marched, he looked neither to the right nor left,—apparently too absorbed to notice the people, many of whom even knelt upon his approach. From the cries that saluted the chief, together with the descriptions he had often heard of him, Orteguilla recognized Guatamozin.

The procession wellnigh passed, and the young Spaniard was studying the devices on the ensigns, when a hand was laid upon his shoulder; turning quickly to the intruder, he saw the prince Io’, whom he was in the habit of meeting daily in the audience-chamber of the king. The prince met his smile and pleasantry with a sombre face, and said, coldly,—

“You have been kind to the king, my father; he loves you; on your hand I see his signet; therefore I will serve you. Arise, and begone; stay not a moment. You were never nearer death than now.”

Orteguilla, scarce comprehending, would have questioned him, but the prince spoke on.

“The chiefs who inhabit here are in the procession. Had they found you, Huitzil’ would have had a victim before sunset. Stay not; begone!”

While speaking, Io’ moved to the curtained doorway from which he had just come. “Beware of the people in the square; trust not to the signet. My father is still the king; but the lords and pabas have given his power to another,—him whom you saw pass just now before the banners. In all Anahuac Guatamozin’s word is the law, and that word is—War.” And with that he passed into the house.

The page was a soldier, not so much in strength as experience, and brave from habit; now, however, his heart stood still, and a deadly coldness came over him; his life was in peril. What was to be done?

The procession passed by, with the multitude in a fever of enthusiasm; then the lad ventured to leave the portico, and start for his quarters, to gain which he had first to traverse the side of the square he was on; that done, he would be in the beautiful street, going directly to the desired place. He strove to carry his ordinary air of confidence; but the quick step, pale face, and furtive glance would have been tell-tales to the shopkeepers and slaves whom he passed, if they had been the least observant. As it was, he had almost reached the street, and was felicitating himself, when he heard a yell behind him. He looked back, and beheld a party of warriors coming at full speed. Their cries and gestures left no room to doubt that he was their object. He started at once for life.

The noise drew everybody to the doors, and forthwith everybody joined the chase. After passing several bridges, the leading pursuers were about seventy yards behind him, followed by a stream of supporters extending to the tianguez and beyond. So we have the scene with which the chapter opens.

The page’s situation was indeed desperate. He had not yet reached the king’s palace, on the other side of which, as he knew, lay a stretch of street frightful to think of in such a strait. The mob was coming rapidly. To add to his horror, in front appeared a body of men armed and marching toward him; at the sight, they halted; then they formed a line of interception. His steps flagged; fainter, but more agonizing, arose his prayer to Christ and the Mother. Into the recesses on either hand, and into the doors and windows, and up to the roofs, and down into the canals, he cast despairing glances; but chance there was not; capture was certain, and then the—SACRIFICE!

That moment he reached a temple of the ancient construction,—properly speaking, a Cû,—low, broad, massive, in architecture not unlike the Egyptian, and with steps along the whole front. He took no thought of its appearance, nor of what it might contain; he saw no place of refuge within; his terror had become a blind, unreasoning madness. To escape the sacrifice was his sole impulse; and I am not sure but that he would have regarded death in any form other than at the hands of the pabas as an escape. So he turned, and darted up the steps; before his foremost pursuer was at the bottom, he was at the top.

With a glance he swept the azoteas. Through the wide, doorless entrance of a turret, he saw an altar of stainless white marble, decorated profusely with flowers; imagining there might be pabas present, and possibly devotees, he ran around the holy place, and came to a flight of steps, down which he passed to a court-yard bounded on every side by a colonnade. A narrow doorway at his right hand, full of darkness, offered him a hiding-place.

In calmer mood, I doubt if the young Spaniard could have been induced alone to try the interior of the Cû. He would at least have studied the building with reference to the cardinal points of direction; now, however, driven by the terrible fear, without thought or question, without precaution of any kind, taking no more note of distance than course, into the doorway, into the unknown, headlong he plunged. The darkness swallowed him instantly; yet he did not abate his speed, for behind him he heard—at least he fancied so—the swift feet of pursuers. Either the dear Mother of his prayers, or some ministering angel, had him in keeping during the blind flight; but at last he struck obliquely against a wall; in the effort to recover himself, he reeled against another; then he measured his length upon the floor, and remained exhausted and fainting.

CHAPTER VI

LOST IN THE OLD CÛ

The page at last awoke from his stupor. With difficulty he recalled his wandering senses. He sat up, and was confronted everywhere by a darkness like that in sealed tombs. Could he be blind? He rubbed his eyes, and strained their vision; he saw nothing. Baffled in the appeal to that sense, he resorted to another; he felt of his head, arms, limbs, and was reassured: he not only lived, but, save a few bruises, was sound of body. Then he extended the examination; he felt of the floor, and, stretching his arms right and left, discovered a wall, which, like the floor, was of masonry. The cold stone, responding to the touch, sent its chill along his sluggish veins; the close air made breathing hard; the silence, absolutely lifeless,—and in that respect so unlike what we call silence in the outer world, which, after all, is but the time chosen by small things, the entities of the dust and grass and winds, for their hymnal service, heard full-toned in heaven, if not by us,—the dead, stagnant, unresonant silence, such as haunts the depths of old mines and lingers in the sunken crypts of abandoned castles, awed and overwhelmed his soul.

Where was he? How came he there? With head drooping, and hands and arms resting limp upon the floor, weak in body and spirit, he sat a long time motionless, struggling to recall the past, which came slowly, enabling him to set the race again with all its incidents: the enemy in rear, the enemy in front; the temple stairs, with their offer of escape; the azoteas, the court, the dash into the doorway under the colonnade,—all came back slowly, I say, bringing a dread that he was lost, and that, in a frantic effort to avoid death in one form, he had run open-eyed to embrace it in another even more horrible.

The dread gave him strength. He arose to his feet, and stood awhile, straining his memory to recall the direction of the door which had admitted him to the passage. Could he find that door, he would wait a fitting time to slip from the temple; for which he would trust the Mother and watch. But now, what was done must needs be done quickly; for, though but an ill-timed fancy, he thought he felt a sensation of hunger, indicating that he had been a long time lying there; how long, of course, he knew not.

Memory served him illy, or rather not at all; so that nothing would do now but to feel his way out. O for a light, if only a spark from a gunner’s match, or the moony gleam of a Cuban glow-worm!

As every faculty was now alert, he was conscious of the importance of the start; if that were in the wrong direction, every inch would be from the door, and, possibly, toward his grave. First, then, was he in a hall or a chamber? He hoped the former, for then there would be but two directions from which to choose; and if he took the wrong one, no matter; he had only to keep on until the fact was made clear by the trial, and then retrace his steps. “Thanks, O Holy Mother! In the darkness thou art with thy children no less than in the day!” And with the pious words, he crossed himself, forehead and breast, and set about the work.