По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

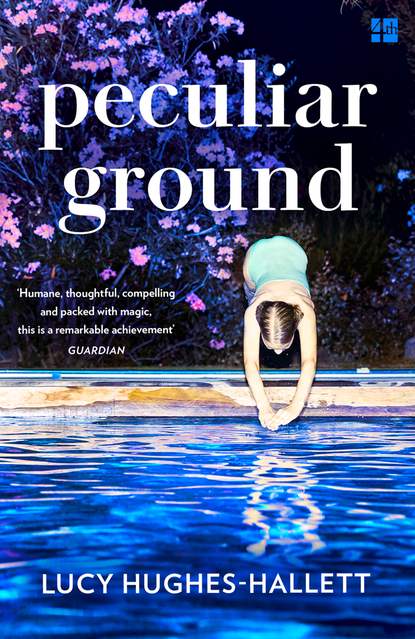

Peculiar Ground

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When Christopher sloped off, Nicholas put in an appearance in the drawing room, drank coffee and bustled about flirting so no one could say he wasn’t doing his bit socially. Then he slipped away too and set up camp in what passed in that house for a cosy study. Linen-fold panelling, a ceiling dripping plaster stalactites. The room had been deprived of one of its walls around the time of the Glorious Revolution, and now formed an L with the pilastered drawing room where Christopher and Lil hung the paintings of which they were properly proud.

He accepted a whisky and soda when Underhill appeared like a well-disciplined genie, drew the curtain across the joint of the L, and settled down in a tapestried chair beneath an upside-down pendent obelisk to try to make sense of the reports that had come in that day. Ted had rung about the Konev story. He’d heard Reuters’ man in Berlin had a hunch that the East Germans were going to do something very soon, but what it was he couldn’t guess. Not exactly what you’d call hard news.

Nicholas began to scribble out a think-piece on the limits of totalitarianism. Khrushchev being as much at the mercy of his party as Kennedy was at the mercy of the American electorate, both of them having to act tough for their respective constituencies, both of them probably clever enough to know it was a charade, the perils into which that play-acting might drag all Europe, de da de da de da de da.

Voices. Antony was showing young Flossie the pictures. The obstreperous Benjie had tagged along.

Flossie – ‘Gosh! Is it a Cimabue?’

‘Yes it is.’

Privately, as Nicholas knew, Antony had his doubts, but he was a loyal friend and a discreet dealer. So yes it unequivocally was.

‘Looks lonely. Is that a bit of his friend on the right?’ Benjie getting in on the conversation.

‘Yes, it appears to be a fragment from the right wing of an altarpiece. See how it is hinged here. There would have been another two or three angels, a heavenly chamber group.’

‘The hands are so . . .’

The hands, indeed, were ineffable.

‘Girly? Or perhaps he is a girl. Or a fag. Look how he’s leaning into the other’s shoulder.’

Was Benjie an ass, thought Nicholas, or was he just pretending to be one? Nicholas had met Helen when she came into the office with her copy – she reviewed for the arts pages occasionally. And they’d talked, and one day they’d had lunch together, and another day they’d walked along the river east from Fleet Street past the Tower and he’d shown her one of his favourite places in London, Wapping Pierhead, where the tall Georgian houses run down to the river’s edge and even the pavements still seem to reek of the cloves and nutmegs that made their first owners rich, and he thought she was beautiful in a steely-cool Celtic kind of way. Her eyes were as pale as gooseberries. There followed some very, very private afternoons in his flat. This was the first opportunity he’d had to observe her husband.

He stepped out from behind his arras. He wasn’t going to get any more work done with them prattling on the other side.

Antony was saying, ‘Either or neither. Angels, being insubstantial, are spared the indignities of sex.’

Benjie poured himself whisky and drifted about the room. He was looking at Flossie as much as at the paintings. Polite girl that she was, she kept making little nods and mmms. There’s nothing harder to sustain than an appearance of interest, even when it’s genuine. She was beginning to look a bit strained when Benjie called her over to see Christopher’s chess-set. Booty of the Raj. Ivory and ebony, laid out on a great scagliola table.

‘Do you play? I’ll give you a game.’

A murmur that was like a verbal blush. Was this rude to Antony? How to reconcile the demands of all these different grown-ups? She had put on a dramatic dress for dinner, low cut, and made of bands of stiff papery silk in clashing bright colours, but for all that, and despite her lacquered hair, she was still a child. ‘All right. You’ll easily beat me.’

‘So I hope.’

Simple words, but uttered as though they had a salacious double meaning. If Benjie wasn’t an ass, he was certainly a bit of a lecher.

The others left them to it, and went out onto the terrace where Lil and Helen were sitting. Nicholas and Lil dropped into the banter that had become their normal mode of conversation. Silly stuff, he thought, but as bracing, she’s so quick, as tennis is for those who are good at it. Christopher loomed up on the rim of the ha-ha, his rod on his shoulder like the Good Shepherd’s crook, and crossed the lawn and joined them and for a while Nicholas felt easier than he had for weeks. The distant events that would occupy him through the night gave way to the immediate. The scents of stocks and jasmine. Pale roses glimmering. The dog collapsing heavily onto the flagstones and sighing like the grampus for whom he was named. He and Helen tended to ignore each other in company, but her being there, near him in the darkness, was a plus.

There was a scraping and a clatter indoors. Flossie came out. She didn’t say anything, just sat herself down in the corner between the great magnolia and Lil, who had to shuffle along the stone bench to make room for her. She looked like a cat mutely complaining about a rainstorm. Murmuring from indoors: Underhill saying, ‘I’ll clear it up, sir.’ Helen made no move. It was pretty clear to everyone what had happened – what sort of thing anyway. Nicholas and Lil kept up their tennis game, giving the girl time to collect herself. Why? wondered Nicholas. Surely it was Helen who needed their solicitude. Ignobly, he was pleased.

Pretty soon they all went up. At midnight Nicholas called the copy-desk, and got handed on to Ted, who wanted a background piece for the Sunday paper on Soviet military capacity. At five in the morning he finally got to bed, while in East Berlin the Stasi prepared to demonstrate that the myth of German efficiency had a basis in fact.

Saturday (#udec14449-5df4-591d-8085-fde11b8d3813)

Nell walked across the cattle grid by Underhill’s lodge, her feet in her sandshoes only just making enough of a bridge from one bar to another to stop her slipping through. Hedgehogs got trapped down there sometimes. She’d been frightened once to hear a rustling, and then so amazed she could still conjure up the prickle of it, to see the dished face. Wild animals, even little funny ones, were like glimpses of another world carrying on with its business in secret, not caring at all about people. Perhaps even being enemies. Hedgehogs had fleas.

She was pushing her bicycle, and once safely over she got back on it, using the brick edge of Mrs Underhill’s delphinium-bed to help herself up. Wood Manor was separated from the park by paddocks and a belt of trees. It had its own feeling, the feeling of home. The feeling inside the park wall was different; quieter somehow, a bit gloomy, old.

Swoop down the hairpin bend, faster than you’d really want to so that you could get most of the way up the slope beyond. The Land Rover passed her, hooting, the canvas roof off and Dickie in the back, waving wildly with both arms. By the time she reached the estate office her father was already walking up the beech avenue with Mr Green the head gardener, and she had to bump and rattle over the pebbly path down the centre of it, with Dickie, because he was annoying, and Wully, because he was so pleased to see her after their half-hour separation, barging into her and making her wobble.

‘We’ll start emptying the pool Sunday, then, once they’ve all gone indoors to dinner. We’ve got all the beans to pick next week so Mrs Duggary can get them in the freezer while Mr and Mrs R are away. And the lettuces’ll be bolting.’

Nell wanted to protest about the pool, because she’d have liked a last swim on Monday morning, but she could tell her father wasn’t really listening. Mr Green liked to keep up a continuous report on his own doings but he didn’t seem to mind talking on and on without anyone saying even ‘mmm’ or ‘really?’ He was just filling the time with his warm buzz until Daddy was ready to tell him whatever needed to be told, and sure enough, after a bit Daddy came back from wherever his thoughts had been and shouted at Wully and started to tell Mr Green about how they would make a new rose garden with a sundial. Nell went ahead, freewheeling down the sloping path that slanted away from the avenue towards the narrow gate that led into the garden, and passed on through the rhododendrons and on down to the pool.

Flossie was floating on her back with her long hair mermaidy around her. Nell was so pleased to see her there she ran into the changing hut and took off her stiff canvas shorts and left them sitting on the floor as though there was a person still in them, and kicked off her sandals and took off her blouse with its Peter Pan collar (surely Peter Pan didn’t look like that) so roughly that a button came off, and ran back out in her best rose-trellised bathing dress with her inner tube and plopped straight in even before Daddy was there.

‘Hello little fish,’ said Flossie.

‘You’re the fish. I’m in my boat.’

‘So you are. Silly old me with my goggley eyes. I thought for a moment you were a totally round flatfish of a previously unknown species.’

Flossie was not a grown-up not a child but something anomalous and exciting like a centaur or a psammead. She ducked her head under the water and when she came up her mouth was an o and she was blowing a bubble like the goldfish. Daddy came through the arched gap in the hedge, hesitated, and then said hello in an odd voice.

‘I can’t speak,’ said Flossie. ‘I’m a fish.’

He laughed then. Mummy would have told Nell off for not waiting but he seemed to think it was all right.

‘Watch out that fishing boat doesn’t spot you. And Nell, if you feel seasick, ask the fish to help you – I think it’s a kind one.’

He went with Dickie into the changing room, the one for boys across the little hallway. On the doors hung girly and boyish things . . . antlers for the boys, a necklace made of nutshells for the girls. Mrs Rossiter had laughed when Green hung them there – ‘Does he suppose we can’t find our way around a hut?’ – but they had stayed, adding to the hut’s oddity. It looked, Nell thought, like a house where savages lived, all made of sticks and straw and things you pick up.

Her father dived in while Dickie lay tummy down on his coracle and flapped his hands. For a while they were all fish. Then they were all water boatmen. And then more grown-ups arrived and Flossie said she was cold, and got out and put on sunglasses, which is something no child ever did so it was as though she had swapped sides. She couldn’t have been that cold because she didn’t go and change but sat down on the low wall between Antony and Nicholas. Daddy got out too and stood in front of them, and Nell had that lonely feeling again because they were all laughing, and Nicholas was teasing Flossie and making Daddy tease her too and it was lovely for them but horrid for her because they had all completely forgotten her and she was left with just Dickie, and the fact that you happened to be in the same family with someone and both of you children absolutely did not mean that that someone was the person you wanted to be left with. Dickie splashed her on purpose, and she was angry and grabbed his coracle and tipped him into the water, which was rather awful because she knew he couldn’t really swim.

‘For goodness sake, is no one watching that child?’

Mrs Rossiter arriving with two people Nell didn’t know. The man kicked off his shoes and jumped in the water with all his clothes on and got hold of Dickie, who was all right really because he was clinging onto the inner tube, just not inside it any more, and dragged him quite roughly to the side of the pool. Dickie was crying and swimming-pool water was coming out of his mouth and nose so he was much more blubbery than the crying by itself would have made him. Nell stayed still, and everything was happening very slowly in bright light. Quiet like her nightmare. Mrs R and Daddy were staring at each other across the pool. They both looked older than usual and as though they had to cling on tight to something or they might fall.

‘So. Lane.’

She never called him Lane. She called him Hugo. Calling people by their surnames meant they were less important. In a way Daddy was less important because he worked for the Rossiters, but usually you couldn’t tell that.

‘If you can’t do your job, you could at least take care of your son. And what on earth are you all doing here in the first place? Get rid of your bloody dog.’

The strange man had climbed out of the pool and Wully was licking his wet ankles. Daddy growled at Wully, and then shouted at Nell, ‘Come on out.’ Then he walked slowly round the pool and said something very quiet to Mrs R, and took Dickie by the hand and walked with him into the changing hut. Nell got out, and ran behind them, but she could hear Nicholas talking in his joking voice again, and saying, ‘Benjie to the rescue! There you were pretending to be a lounge-lizard and all the time we had a hero in our midst.’

She could see the man called Benjie taking off his wet trousers and she could hardly believe it. Underneath he wasn’t wearing bum-bags like the ones Daddy wore but tiny knicker-shaped swimming trunks like Dickie’s, but they weren’t all woolly, they were shiny and slithery like snakeskin, and the most amazing thing was that they were patterned with green and purple scales just like a snake.

*

So what about Nell’s mother? Why was she so seldom in evidence? Because she didn’t want to be, is why.

Chloe Lane had realised that to be inconspicuous was a precious pass to freedom. Chloe’s so sweet, said Lil. Chloe, could you be an angel and . . . Chloe, I cannot think what to do about . . . Why not ask Chloe? She’d do it (open the fête, chair the WVS, judge the school’s dressing-up competition) so much better than me . . . Chloe fits in so perfectly! I don’t know why I always look like a cockatoo . . . Chloe’s so clever with flowers . . . Chloe’s so clever . . .

Every single one of Lil’s compliments was an order, or a demand, or a subtle derogation. At Wood Manor Chloe was her own and her servants’ and children’s mistress. At Wychwood she was the agent’s wife. She stayed away. Dancing attendance was Hugo’s job.