По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

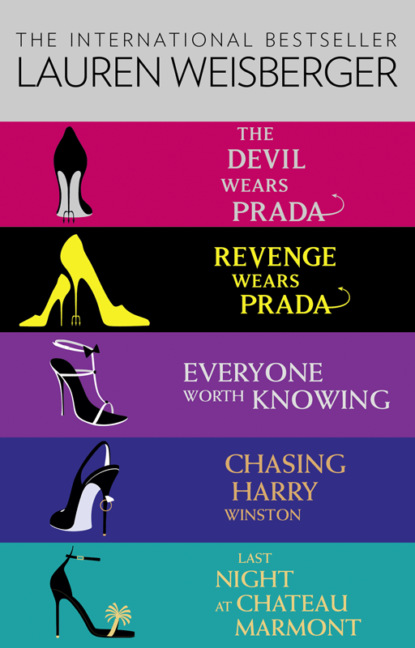

Lauren Weisberger 5-Book Collection: The Devil Wears Prada, Revenge Wears Prada, Everyone Worth Knowing, Chasing Harry Winston, Last Night at Chateau Marmont

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘So, little Andy, did I show you a good time tonight?’ he slurred just a little bit, and it seemed nothing short of adorable at that moment.

‘It was all right, I suppose.’

‘Just all right? Sounds to me like you wish I would’ve taken you upstairs tonight, huh, Andy? All in good time, my friend, all in good time.’

I smacked him playfully on the forearm. ‘Don’t flatter yourself, Christian. Thank your parents for me.’ And, for once, I leaned over first and kissed him on the cheek before he could do anything else. ‘G’night.’

‘A tease!’ he called, slurring just a little bit more. ‘You’re quite the little tease. Bet your boyfriend loves that about you, doesn’t he?’ He was smiling now, and not cruelly. It was all part of the flirty game for him, but the reference to Alex sobered me for a minute. Just long enough to realize that I’d had a better time tonight than I could remember having had in many years. The drinking and the close dancing and his hands on my back as he pulled me against him had made me feel more alive than in all the months since I’d been working at Runway, months that had been filled with nothing but frustration and humiliation and a body-numbing exhaustion. Maybe this was why Lily did it, I thought. The guys, the partying, the sheer joy of realizing you’re young and breathing. I couldn’t wait to call and tell her all about it.

Miranda joined me in the backseat of the limo after another five minutes, and she even appeared to be somewhat happy. I wondered if she’d gotten drunk but ruled that out immediately: the most I’d ever seen her drink was a sip of this or that, and then only because a social situation demanded it. She preferred Perrier to champagne and certainly a milkshake or a latte to a cosmo, so the chances she was actually drunk right now were slim.

After grilling me about the following day’s itinerary for the first five minutes (luckily I’d thought to tuck a copy in my bag), she turned and looked at me for the first time all evening.

‘Emily – er, Ahn-dre-ah, how long have you been working for me?’

It came out of left field, and my mind couldn’t work fast enough to figure out the ulterior motive for this sudden question. It felt strange to be the object of any question of hers that wasn’t explicitly asking why I was such a fucking idiot for not finding, fetching, or faxing something fast enough. She’d never actually asked about my life before. Unless she remembered the details of our hiring interview – and it seemed unlikely, considering she’d stared at me with utterly blank eyes my very first day of work – then she had no idea where, if anywhere, I’d attended college, where, if anywhere, I lived in Manhattan, or what, if anything, I did in the city in the few precious hours a day I wasn’t racing around for her. And although this question most certainly did have a Miranda element to it, my intuition said that this might, just maybe, be a conversation about me.

‘Next month it will be a year, Miranda.’

‘And do you feel you’ve learned a few things that may help you in your future?’ She peered at me, and I instantly suppressed the urge to start rattling off the myriad things I’d ‘learned’: how to find a single store or restaurant review in a whole city or out of a dozen newspapers with few to no clues about its genuine origin; how to pander to preteenage girls who’d already had more life experiences than both my parents combined; how to plead with, scream at, persuade, cry to, pressure, cajole, or charm anyone, from the immigrant food delivery guy to the editor in chief of a major publishing house to get exactly what I needed, when I needed it; and, of course, how to complete just about any challenge in under an hour because the phrase ‘I’m not sure how’ or ‘that’s not possible’ was simply not an option. It had been nothing if not a learning-rich year.

‘Oh, of course,’ I gushed. ‘I’ve learned more in one year working for you than I could’ve hoped to have learned in any other job. It’s been fascinating, really, seeing how a major – the major – magazine runs, the production cycle, what all the different jobs are. And, of course, being able to observe the way you manage everything, all the decisions you make – it’s been an amazing year. I’m so thankful, Miranda!’ So thankful that two of my molars had been aching for weeks, too, but I wasn’t ever able to get in to see a dentist during working hours, but whatever. My newfound, intimate knowledge of Jimmy Choo’s handicraft had been well worth the pain.

Could this possibly sound believable? I stole a glance, and she seemed to be buying it, nodding her head gravely. ‘Well, you know, Ahn-dre-ah, that if ah-fter a year my girls have performed well, I consider them ready for a promotion.’

My heart surged. Was it finally happening? Was this where she told me that she’d already gone ahead and secured a job for me at The New Yorker? Never mind that she had no idea I would kill to work there. Maybe she had just figured it out because she cares.

‘I have my doubts about you, of course. Don’t think I haven’t noticed your lack of enthusiasm, or those sighs or faces you make when I ask you to do something that you quite obviously don’t feel like doing. I’m hoping that’s just a sign of your immaturity, since you do seem reasonably competent in other areas. What exactly are you interested in doing?’

Reasonably competent! She may as well have announced I was the most intelligent, sophisticated, gorgeous, and capable young woman she’d ever had the pleasure of meeting. Miranda Priestly had just told me I was reasonably competent!

‘Well, actually, it’s not that I don’t love fashion, because of course I do. Who wouldn’t?’ I rushed on to say, keeping a careful appraisal of her expression, which, as usual, remained mostly unchanged. ‘It’s just that I’ve always dreamt of becoming a writer, so I was hoping that might, uh, be an area I could explore.’

She folded her hands in her lap and glanced out the window. It was clear that this forty-five-second conversation was already beginning to bore her, so I had to move quickly. ‘Well, I certainly have no idea if you can write a word or not, but I’m not opposed to having you write a few short pieces for the magazine to find out. Perhaps a theater review or a small writeup for the Happenings section. As long as it doesn’t interfere with any of your responsibilities for me, and is done only during your own time, of course.’

‘Of course, of course. That would be wonderful!’ We were talking, really communicating, and we hadn’t so much as mentioned the words ‘breakfast’ or ‘dry cleaning’ yet. Things were going too well not to just go for it, and so I said, ‘It’s my dream to work at The New Yorker one day.’

This seemed to catch her now drifting attention, and once again she peered at me. ‘Why ever would you want to do that? No glamour there, just nuts and bolts.’ I couldn’t decide if the question was rhetorical, so I played it safe and kept my mouth shut.

My time was about twenty seconds from expiring, both because we were nearing the hotel and her fleeting interest in me was fading fast. She was scrolling through the incoming calls on her cell phone, but still managed to say in the most offhanded, casual way, ‘Hmm, The New Yorker. Condé Nast.’ I was nodding wildly, encouragingly, but she wasn’t looking at me. ‘Of course I know a great many people there. We’ll see how the rest of the trip goes, and perhaps I’ll make a call over there when we return.’

The car pulled up to the entrance, and an exhausted-looking Monsieur Renaud eclipsed the bellman who was leaning forward to open Miranda’s door and opened it himself.

‘Ladies! I hope you had a lovely evening,’ he crooned, doing his best to smile through the exhaustion.

‘We’ll be needing the car at nine tomorrow morning to go to the Christian Dior show. I have a breakfast meeting in the lobby at eight-thirty. See that I’m not disturbed before then,’ she barked, all traces of her previous humanness evaporating like spilled water on a hot sidewalk. And before I could think how to end our conversation or, at the very least, kiss up a little more for having had it at all, she walked toward the elevators and vanished inside one. I shot a weary, understanding look to Monsieur Renaud and boarded an elevator myself.

The small, tastefully arranged chocolates on a silver tray on my bedside table only highlighted the perfection of the evening. In one random, unexpected night, I’d felt like a model, hung out with one of the hottest guys I’d seen in the flesh, and had been told by Miranda Priestly that I was reasonably competent. It felt like everything was finally coming together, that the past year of sacrifice was showing the first early signs of potentially paying off. I collapsed on top of the covers, still fully dressed, and gazed at the ceiling, still unable to believe that I’d told Miranda straight up that I wanted to work at The New Yorker, and she hadn’t laughed. Or screamed. Or in any way, shape, or form freaked out. She hadn’t even scoffed and told me that I was ridiculous for not wanting to get promoted somewhere within Runway. It was almost as though – and I might be projecting here, but I don’t think so – she had listened to me and understood. Understood and agreed. It was almost too much to comprehend.

I undressed slowly, making sure to savor every minute of tonight, going over and over in my mind the way Christian had led me from room to room and then all over the dance floor, the way he looked at me through those hooded lids with the persistent curl, the way Miranda had almost, imperceptibly, nodded when I’d said what I really wanted was to write. A truly glorious night, I had to say, one of the best in recent history. It was already three-thirty in the morning Paris time, making it nine-thirty New York time – a perfect time to catch Lily before she went out for the night. Although I should’ve just dialed with no regard for the insistent, blinking light that announced – surprise, surprise – that I had messages, I cheerfully pulled out a pad of the Ritz stationery and got ready to transcribe. There were bound to be long lists of irritating requests from irritating people, but nothing could take away my Cinderella-esque evening.

The first three were from Monsieur Renaud and his assistants, confirming various drivers and appointment for the next day, always remembering to wish me a good night as though I were actually a person instead of just a slave, which I appreciated. Between the third and the fourth message I found myself both wishing and not wishing that one of the messages to come was from Alex, and as a result, was both delighted and anxious when the fourth was from him.

‘Hi, Andy, it’s me. Alex. Listen, I’m sorry to bother you over there, I’m sure you’re incredibly busy, but I need to talk to you, so please call me on my cell phone as soon as you get this. Doesn’t matter how late it is, just be sure to call, OK? Uh, OK. ’Bye.’

It was so strange that he hadn’t said he loved me or missed me or was waiting for me to get back, but I guess all those things fall squarely into the ‘inappropriate’ category when people decide to ‘take a break.’ I hit delete and decided, rather arbitrarily, that the lack of urgency in his voice meant I could wait until tomorrow – I just couldn’t handle a long ‘state of our relationship’ conversation at three o’clock in the morning after as wonderful a night as I’d just had.

The last and final message was from my mom, and it, too, sounded strange and ambiguous.

‘Hi, honey, it’s Mom. It’s about eight our time, not sure what that makes it for you. Listen, no emergency – everything’s fine – but it’d be great if you could call me back when you hear this. We’ll be up for a while, so anytime is fine, but tonight is definitely better than tomorrow. We both hope you’re having a wonderful time, and we’ll talk to you later. Love you!’

This was definitely strange. Both Alex and my mother had called me in Paris before I’d gotten a chance to call either of them, and both had requested that I call them back regardless of what time I got the message. Considering my parents defined a late night by whether or not they managed to stay awake for Letterman’s opening monologue, I knew something had to be up. But at the same time, no one sounded particularly panicked or even a little frantic. Perhaps I’d take a long bubble bath with some of the Ritz products provided and slowly work up the energy to call everyone back; the night had just been too good to wreck by talking to my mother about some petty concern or to Alex about ‘where we stand.’

The bath was just as hot and luxurious as you’d expect it to be in a junior suite adjacent to the Coco Chanel suite at the Ritz Paris, and I took a few extra minutes to apply some of the lightly scented moisturizer from the vanity to my entire body. Then, finally wrapped in the plushest terry-cloth robe I’d ever pulled around me, I sat down to dial. Without thinking, I dialed my mother first, which was probably a mistake: even her ‘hello’ sounded seriously stressed out.

‘Hey, it’s me. Is everything OK? I was going to call you guys tomorrow, it’s just that things have been so hectic. But, wait until I tell you about the night I just had!’ I knew already that I’d be omitting any romantic references to Christian, since I hadn’t felt like explaining the entire Alex scenario to my parents, but I knew they’d both be thrilled to hear that Miranda seemed to respond well when I’d brought up the idea of The New Yorker.

‘Honey, I don’t mean to interrupt you, but something’s happened. We got a call today from Lenox Hill Hospital, which is on Seventy-seventh Street, I think, and it seems that Lily’s been in an accident.’

And although it’s quite conceivably the most clichéd expression in the English language, my heart stopped for just a moment. ‘What? What are you talking about? What kind of an accident?’

She had already switched into worried-mom mode and was clearly trying to keep her voice steady and her words rational, following what was sure to have been my dad’s suggestion of passing along to me a feeling of calm and control. ‘A car accident, honey. A rather serious one, I’m afraid. Lily was driving – there was also a guy in the car, someone from school, I think they said – and she turned the wrong way down a one-way street. It seems she hit a taxicab head-on, going nearly forty miles an hour on a city street. The police officer I spoke with said it was a miracle she’s alive.’

‘I don’t understand. When did it happen? Is she going to be OK?’ I had started choke-crying at some point, because as calm as my mother was trying to remain, I could hear the severity of the situation in her carefully chosen words. ‘Mom, where is Lily now, and is she going to be OK?’

It wasn’t until this point that I noticed my mom was crying also, just quietly. ‘Andy, I’m putting Dad on. He spoke to the doctors most recently. I love you, honey.’ The last part came out like a squeak.

‘Hi, honey. How are you? Sorry we have to call with news like this.’ My dad’s voice sounded deep and reassuring, and I had a fleeting feeling that everything was going to work out. He was going to tell me that she’d broken her leg, maybe a rib or two, and someone had called in a good plastic surgeon to stitch up a few scrapes on her face. But she was going to be just fine.

‘Dad, will you please tell me what happened? Mom said Lily was driving and hit a cab going really fast? I don’t understand. None of this makes any sense. Lily doesn’t have a car, and she hates to drive. She’d never be cruising around Manhattan. How did you hear about this? Who called you? And what’s wrong with her?’ Again, I’d worked myself up to nearly hysterical, but again his voice was commanding and soothing all in one.

‘Take a deep breath – I’ll tell you everything I know. The accident happened yesterday, but we just found out about it today.’

‘Yesterday! How could this have happened yesterday and no one called me? Yesterday?’

‘Sweetie, they did call you. The doctor said that Lily had filled out the front information page in her daily planner and had listed you as her emergency contact, since her grandmother’s really not doing all that well. Anyway, I guess the hospital called you at home and on your cell, but of course you weren’t checking either one. When no one called them back or showed up in twenty-four hours, they went through her planner and noticed that we have the same last name as you, and so the hospital called here to see if we knew how to reach you. Mom and I couldn’t remember where you were staying, so we called Alex for the name of the hotel.’

‘Oh my god, it was a day ago. Has she been alone this whole time? Is she still in the hospital?’ I couldn’t ask the questions fast enough, but I still felt like I wasn’t getting any answers. All I knew for sure was that Lily had decided on me as the primary person in her life, the emergency contact you always had to list but never, ever took seriously. And here she’d really needed me – didn’t have anyone else, in fact – and I’d been nowhere to be found. My choking had subsided, but the tears continued to pour down my cheeks in hot, angry streaks, and my throat felt as though it had been scraped raw with a pumice stone.

‘Yes, she’s still in the hospital. I’m going to be very honest with you, Andy. We’re not sure if she’s going to be all right.’

‘What? What are you saying? Will someone just tell me something concrete already?’

‘Honey, I’ve spoken to her doctor a half-dozen times already, and I have complete confidence that she’s getting the best attention. But Lily’s in a coma, sweetie. Now, the doctor did reassure me that—’

‘A coma? Lily is in a coma?’ Nothing was making sense anymore; the words were refusing to take on meaning.

‘Honey, try to calm down. I know this is shocking for you and I hate to do this over the phone. We considered not telling you until you got back, but since that’s still half a week away, we figured you had a right to know. But also know that Mom and I are doing everything we can to make sure that Lily gets the best help. She’s always been like a daughter to us, you know that, so she’s not going to be alone.’