По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

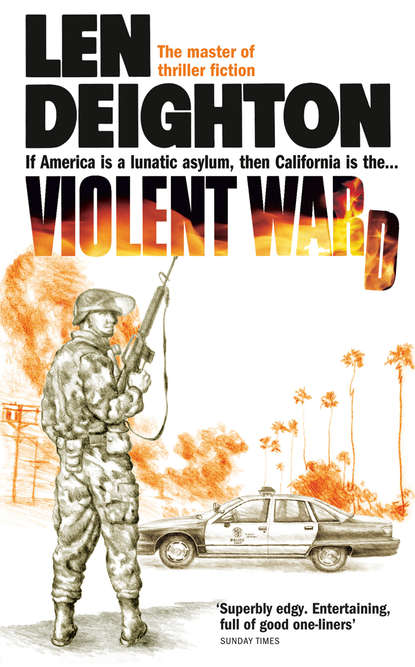

Violent Ward

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Coffee? A drink?’

‘Perrier water,’ said Budd. To complete the costume, he was wearing a beautiful gray fedora, which he took off and carefully placed on a shelf.

I went to the refrigerator hidden in the bookcase and brought him a club soda. ‘Cigarette?’ I picked up the silver box on my desk and waved it at him.

He shook his head. I can’t remember the last time someone said yes. One day someone was going to puff at one of those ancient sticks and spew their guts out all over my white carpet.

‘I read the other day the UCLA School of Medicine calculated that one joint has the carbon monoxide content of five regular cigarettes and the tar of three,’ Budd said.

‘These are not joints,’ I said, shaking the silver box some more.

Budd laughed. ‘I know. I just wanted to impress you with my learning.’

‘You did.’

Budd didn’t have to work hard at being a charmer: it just came natural to him. We’d stayed in touch since he abandoned Social Sciences in favor of Actors’ Equity. He’d made a modest rep and his face was known to those who spent a lot of time in the dark, but he expended every last cent he earned keeping up a standard of living way beyond his means because he had to pretend to himself and everyone else that he was a big big star. I suppose only someone permanently out of touch with reality tried for the movie big time in Hollywood. The soup kitchens and retirement homes echo with the chatter of people still talking about the big chance that’s coming any day. But Budd was not permanently out of touch with reality, just now and again. As the smart-ass student editor of our college yearbook wrote of him, his head was in the clouds but his feet were planted firmly on the ground. He really enjoyed what he did for a living, whether it was first class acting or not. Back in the forties, when movie stars were youthful and wholesome and gentlemanly, Budd might have made it big – or even in that brief period in the sixties when the collegiate look was in style – but nowadays it was stubble-chinned mumbling degenerates who got their names above the title. Budd was out of style.

‘You are coming to my little champagne-and-burger birthday bash?’ said Budd.

‘You couldn’t keep me away,’ I said. I’d received an elaborate printed invitation to a luncheon party at Manderley, his old house perched up in the Hollywood Hills, near the Laurel Canyon intersection. Budd was one of those people who keeps in touch. He always knew what all his old classmates were doing, and when reunion time came round he was there addressing the envelopes.

‘Lunch, a week from Sunday. We’ll keep going until the champagne runs out.’

‘Sounds like a challenge.’

He shifted in his chair, ran a fingernail down his cheek, and spoke in a different sort of voice. ‘Mickey, I need advice. You’re my attorney, right?’

‘You don’t need an attorney,’ I told him. ‘You’re too smart. If all my clients kept their noses clean the way you do, I’d be out of business.’ It was true. I sent hurry-up letters and sorted out the occasional misunderstanding, but most of what I did for Budd could have been done by a part-time secretary. Maybe I didn’t charge him enough.

He nodded and smiled some more and looked out of the window. ‘This is a lousy neighborhood, Mickey.’

‘I know, all my visitors tell me. But we got cops on every corner and great ethnic food. What can I do for you, Budd?’

A pause, a tightening of the jaw. ‘Would you get me a gun?’

‘A gun? What do you want a gun for?’ I said, keeping my voice very steady and matter-of-fact.

‘No special reason,’ he said, in that nervous way people say such things when they do have a special reason. Then came the prepared answer: ‘The way I see it, the law will be putting all kinds of new restrictions on gun sales before long. I want to get a gun while it’s still legal to purchase them over the counter.’

‘I guess you saw that TV documentary on the Discovery channel. But you don’t need a gun, Budd.’

‘I do. My place is very vulnerable up there. There have been two stickups in the doughnut shop since Christmas. My neighbors have all had break-ins.’

‘And having a gun will keep you from being burglarized? Listen, the chances of someone breaking in while you’re there are nearly zero. When you’re not there, a gun won’t be any good to you, right?’

‘It would make me feel better.’

‘Okay. So you made up your mind. Don’t listen to me; buy a gun.’

‘I’d like you to purchase it.’

‘Come on, Budd. What’s the problem?’

‘I’ll be recognized. My face is known. Maybe it will get into the papers. That’s not the kind of publicity I want.’

‘Buying a gun? If that was the secret of getting newspaper publicity, there’d be lines forming outside the gun shops and all the way to the Mexican border.’

‘The paperwork and license and all that stuff. You know about that, Mickey. You do it for me, will you?’

‘You mean within the implied confidentiality of the client-attorney relationship?’

He nodded.

I sat back in my swivel chair and looked at him. Just as I thought I’d heard everything, along comes a client who wants me to buy a heater without his name on it. Next he’s going to be asking me to file off the identity marks and make dum-dum cuts in the bullets. ‘I’m not sure I can do that, Budd,’ I said, very slowly. ‘I’m not sure it’s within the law.’

He caught at the equivocation. ‘Will you find out? It’s the way I’d like it done. Couldn’t you say it was for a well-known movie actor who wanted to avoid the fuss?’

‘Sure. And I’ll promise them signed photos and tickets for your next preview.’ As he started to protest, I held up a hand to deflect it. ‘I’ll ask around, Budd.’

‘A Saturday-night special or a small handgun would do. I just want it as a frightener.’

‘Sure, I understand: no hand grenades or heavy mortars. Can you use a gun? You were never in the military, were you?’

‘I was in ROTC,’ said Budd, the hurt feelings clearly audible in his voice. ‘You know I was, Mickey.’

‘Sure, I forgot.’

‘I can shoot. I’ve had a lot of movie parts using guns. I like to get these things exactly right for my roles. I do an hour in the gym every day. I jog in the hills, and sometimes I go to the Beverly Hills Gun Club.’ He slapped his gut. ‘I keep myself in shape.’

‘Right,’ I said. Well, wind in the target; he sure scored a bull’s-eye with that one. The only thing I could sincerely say I devoted at least one hour every day to was eating.

‘Am I keeping you too long?’ he said, consulting the Rolex with solid gold band that came with every Actors’ Equity card.

‘No rush. I’m going to see Danny: my son, Danny.’

‘Sure, Danny. You brought him and his girlfriend along to watch me on the set of that Western I did for Disney last year.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Give Danny my very best wishes. Tell him if he wants to visit a studio again I can always fix it up for him.’

‘Thanks, Budd. That’s really nice of you. I’ll tell him.’

Budd didn’t get up and leave. He reached out for his glass and took a sip, taking his time doing it, as I had seen so many witnesses on the stand do, buying time to think. ‘I haven’t told you the whole truth. There’s something else. And I want to keep it just between the two of us, okay?’

‘The client-attorney privileged relationship,’ I said.

He got to his feet and nodded. All my clients like hearing about the confidential relationship the attorney offers; I always remind them about it just before I give them my bill. Prayer, sermon, confession, and atonement: in that order. I figure the whole process of consulting an attorney should be a secular version of the mass.