По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

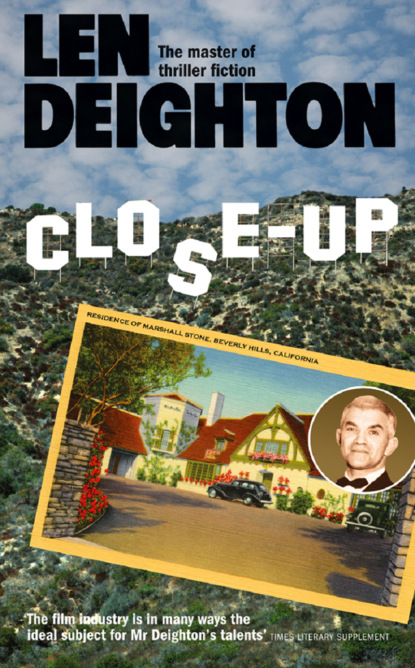

Close-Up

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Epitome Screen Classics – that’s Koolman’s new subsidiary – want TV rights for resale.’

Stone released the agent’s hand. ‘Do you realize that we only see each other to talk business, Viney? Couldn’t we get together regularly – just for laughs, just for old time’s sake?’

‘I don’t know why they let us have that approval clause in the contract. I’d put it in to sacrifice it for something else.’ Viney shook his head sadly. ‘They left it in.’

‘Business! That’s all you think about. Have a drink.’ Stone cocked his head and nodded, as if the affirmative gesture would change his guest’s mind. Back in the days when ventriloquism was a popular form of entertainment, such physical mannerisms had encouraged wisecracks about the cocky little star being seated upon the knee of the doleful giant who was his agent. But these jokes had only been made by people who hadn’t encountered Marshall Stone.

‘No thanks, Marshall.’ He looked at his notes: ‘“Three years after completion of principal photography or by agreement.” It’s only got six months to go anyway.’

‘A small bourbon: Jack Daniels. Remember how we used to drink Jack Daniels in the Polo Lounge at The Beverly Hills?’

Weinberger looked around the huge room to find a suitable space for his papers. Arranged upon an inlaid satinwood table there were ivory boxes, photos in silver frames, instruments to measure pressure, temperature and humidity, a letter-opener and a skeleton clock. Weinberger moved some of the objets d’art and used a small gold pencil to make a cross on both letters. ‘It needs your signature: here and here.’ He put the pencil away and produced a fountain-pen which he uncapped and then tested before presenting to his client.

Stone signed the letters carefully, ensuring that his signature was the same precise work that it always was.

‘Read it, Marshall, read it!’

‘You don’t want me interfering with your end of it.’ He capped the pen and handed it back. ‘What movie are we talking about, anyway?’

‘Sorry, Marshall. I’m talking about Last Executioner. So many shows are losing sponsors that they want to network it in the States to kick off the fall season. It looks like the Vietnam War is going to be the only TV show that will last out till Christmas.’ Stone nodded solemnly.

‘Except for the scene on the boat, I was terrible.’

‘They’ll want the sequels too. Leo said you gave a great performance. “Marshall gave a sustained performance – conflict, colour and confrontation.” You got all three of Leo’s ultimates.’

‘What does that schmuck know about acting.’

‘I agree with him, Marshall. Think of that first script – you built that character out of nothing.’

‘Five writers they used. Six, if you include that kid that they brought in at the end for additional dialogue.’

‘On TV they’ll be a sensation. Leo would like you to do a couple of appearances.’ Weinberger watched the actor’s face, wondering how he would react. He did not react.

‘And it was the kid that got the screenplay credit. For a week’s work!’

Weinberger said, ‘Serious stuff: the Film Institute lecture for the BBC and David Frost for the States – taped here if you prefer – and Koolman would put his whole publicity machine to work. We could get it all in writing.’

‘They’ll sink without a ripple, Viney.’

‘No, Marshall. If the TV companies slot them right they could be very big. And Leo is high on the spy bit at the moment.’

‘I don’t need TV, Viney, I’m not quite that far over the hill: not quite.’ Stone chuckled. ‘Anyway, they’ll die, a successful US TV show must appeal to a mental age of seven.’

‘A lot of TV viewers don’t have a mental age of seven. I like TV.’

‘No, but the men who buy the shows do have a mental age of seven, Viney.’ Stone poured himself a glass of Perrier water and sipped it carefully. He knew that the contract was just an excuse. His agent’s real purpose was to talk about TV work.

‘Now come on, Marshall.’

‘Screw TV, Viney. Let’s not start that again. All you have to do is nod and then take your ten per cent. I’ve got just one career but you’ve got plenty of Marshall Stones in the fire.’ He smiled and held the smile in a way that only actors can.

Weinberger was still holding his fountain-pen and now he looked closely at it. The very tips of his knuckles were white. Stone went on, ‘Like that blond dwarf Marshall Stone, named Val Somerset! You made sure he got his pic in the paper having dinner with the Leo Koolmans at Cannes. Good publicity, that: national papers, not just the trades. Is that why you didn’t want me to go along when Snap, Crackle, Pop was shown there?’ Stone said the words in a low pleasant voice, but he allowed a trace of his anger to show. He had been bottling up that particular grievance for several months.

‘Of course not.’

‘Of course not! Have you seen what he does in Imperial Verdict? The whole performance is what I did in Perhaps When I Come Back. Three people have mentioned it – a straight steal.’

Weinberger went across to the sofa, opened his black leather document-case and put the papers into it.

Stone said, ‘Will you please answer me.’

Weinberger turned and spoke very quietly. ‘That kid isn’t going to take any business from you, Marshall. You are an international star, Val’s name’s not dry in Spotlight. He’s getting a tenth of your price.’

Stone walked across to his agent, paused for a moment, shook his head regretfully and then gripped Weinberger’s arm. It was a gesture he used to pledge affection. ‘Sometimes I wonder how you put up with me, Viney.’

Weinberger didn’t answer. He had been close to Stone for a quarter of a century. He’d learned to endure the criticisms and insults that were a part of the job. He knew the sort of doubts and fears that racked any actor and he knew that an agent must be a scapegoat as well as confessor, friend and father.

In human terms Stone might have benefited from a few home truths. He might have become more of a human being, but such tactics could cripple him as an actor.

And for Weinberger, Stone was by no means ‘any actor’, he was a giant. His Hamlet had been compared with Gielgud’s, and his Othello bettered only by Olivier. On the screen he’d tackled everything from Westerns to light comedy. Not even his agent could claim that they all had been successful but some of his performances remained definitive ones. Few young actors would attempt a cowboy role without having Last Vaquero screened for them, and yet that was Stone’s first major role in films. Weinberger smiled at his client. ‘Forget it, Marshall.’

Stone patted his arm again and walked to the fireplace. ‘Thanks for sending that Man From the Palace script, Viney. You have a fantastic talent for choosing scripts. You should have become a producer. Perhaps I did you no favour in asking you to be an agent.’ Again Stone smiled.

‘I’m glad you like it.’ Weinberger knew that he was being subjected to Stone’s calculated charm but that did not protect him from its effects. Just as confidence tricksters and scheming women do nothing to conceal their artifice, so Stone used his charm with the abrupt, ruthless and complacent skill with which a mercenary might wield a flame-thrower.

‘Do you know something, Viney: it might be great. There’s one scene where I come in from the balcony after the fleet have mutinied. The girl is waiting. I talk to her about the great things I’ve wanted to do for the country… It’s got a lot of social awareness. I’m the man in the middle. I can see the logic of the computer party and the trap awaiting the protestors. It’s got a lot to say to the kids, that film, Viney. Who’s going to play the girl?’

‘Nellie Jones can’t do it, they won’t give her a stop-date on Wild Men, Wild Women and they are four weeks over. Now I hear they’re testing some American girl.’

‘American! Haven’t we got any untalented inexperienced stupid actresses here in England, that they have to go to America to find one.’ Stone laughed grimly; he had to play opposite these girls.

Weinberger smiled as if he’d not heard Stone say the same thing before. ‘I told them how you would feel. You’ll only consider it if the rest of the package is right. But I didn’t say that a new kid wouldn’t be OK. If the billing was right.’

‘Only me above title?’

‘That’s what I had in mind,’ admitted Weinberger.

‘Perhaps it would be better like that.’

‘No rush, Marshall. Let’s see what they come up with: we have the final say.’

‘It’s a good story, Viney.’

‘It was a lousy book,’ warned Weinberger.

‘Eighteen weeks on the best-seller list.’

Weinberger pulled a face.