По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

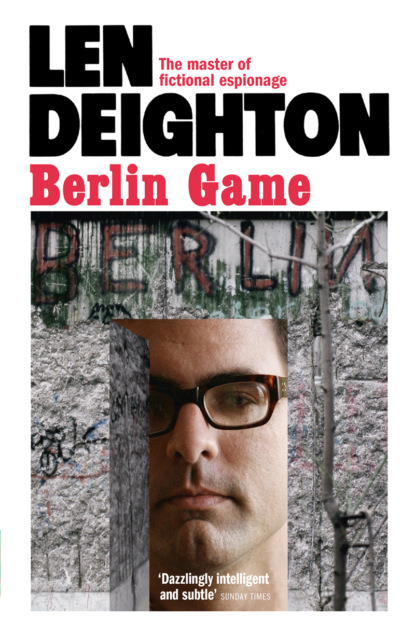

Berlin Game

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Fiona, who hated anything fried in batter, waved a hand as I offered her the plate. I took one, blew on it, and ate it. It wasn’t bad.

‘We’ll manage now, Mrs Dias,’ said Fiona airily. I twisted round to see Mrs Dias standing at the door watching us with a big smile. She disappeared into the kitchen again. There was a cloud of smoke and a loud crash which we all pretended not to hear.

I said to Tessa, ‘How do you know he’s passing stuff to the Russians?’

‘He told me,’ she said.

‘Just like that?’

‘We’d started off in the middle of the afternoon drinking at some funny little club in Soho while Giles was watching the horses on TV. He won some money on one of the races and we went to the Ritz. We’d met a few friends by then, and Giles wanted to impress everyone by giving them dinner. I suggested Annabel’s – George is a member. We stayed there late and Giles turned out to be a super dancer …’

‘Is this all leading up to something he told you in bed?’ I said wearily.

‘Well, yes. We went back to this dear little place he has off the King’s Road. And I’d had a few drinks, and to tell you the truth I thought of George with all those Oriental popsies and I thought, what the hell. And I let Giles talk me into staying there.’

‘What exactly did he say, Tessa? Because it’s nearly half past eight and I’m getting hungry.’

‘He woke me up in the middle of the night. It was absolutely ghastly. He sat up in bed and howled. It was positively orgasmic, darling. You’ve no idea. He howled for help or something. It was a nightmare. I mean, I’ve had nightmares and I’ve seen other people having nightmares – at school half the girls in the dorm had nightmares every night, didn’t they, Fi? – but not like this. He was bathed in sweat and trembling like a leaf.’

‘Giles Trent?’ I said.

‘Yes, I know. It’s hard to imagine, isn’t it? I mean he’s so damned stiff-upper-lip and Grenadier Guards. But there he was shouting and having this nightmare. I had to shake him for ages before he awoke.’

Fiona said, ‘Tell Bernie what he was shouting.’

‘He shouted, “Help me! They made me do it,” and “Please please please.” Then I went and got him a big drink of Perrier water. He said that was what he wanted. He pulled himself together and seemed all right again. And then he suddenly asked me what I’d say if he told me he was a spy for the Russians. I said I’d laugh. And he nodded and said, well, it was true anyway. So I said, for money, do you do it for money? I was joking because I thought he was joking, you see.’

‘So what did he say about money?’ I asked.

‘I knew he wasn’t short of money,’ said Tessa. ‘He was at Eton and he knows anyone who’s anyone. He has the same tailor as Daddy, and he’s not cheap. And Giles is a member of so many clubs and you know how much club subscriptions cost nowadays. George is always on about that, but he has to take business people out, of course. But Giles never complains about money. His father bought him the freehold of this place where he lives and gave him an allowance that is enough to keep body and soul together.’

‘And he has his salary,’ I said.

‘Well, that doesn’t go far, Bernie,’ said Tessa. ‘How do you imagine you and Fiona would manage if all she had was your salary?’

‘Other people manage,’ I said.

‘But not people like us,’ said Tessa in a voice of sweet reasonableness. ‘Poor Fiona has to buy Sainsbury’s champagne because she knows you’ll grumble if she gets the sort of champers Daddy drinks.’

Hurriedly Fiona said, ‘Tell Bernie what Giles said about meeting the Russian.’

‘He told me about meeting this fellow from the Trade Delegation. Giles was in a pub somewhere near the Portobello Road one night. He likes finding new pubs that no one knows about except the locals. It was closing time. He asked the publican for another drink and they wouldn’t serve him. Then a man standing at the counter offered to take him to a chess club in Soho – Kar’s Club in Gerrard Street. There’s a members’ bar there which serves drinks until three in the morning. This Russian was a member and offered to put Giles up for membership and Giles joined. It’s not much of a place, from what I can gather – arty people and writers, and so on. He plays chess rather well, and it began to be a habit that he went there regularly and played the Russian, or just watched someone else playing.’

‘When was the night of this nightmare?’ I said.

‘I don’t remember exactly, but a little while ago.’

‘And he’s told you about the Russians on several occasions. Or just that once in the middle of the night?’

‘I brought it up again,’ said Tessa. ‘I was curious. I wanted to find out if it was a joke or not. Giles Trent remembered your name, and he knows Fiona too, so I guessed that he was on secret work of some kind. Last Friday, we got back to his place very late and he was showing me this electronic chess-playing machine he’d just bought. I said that he wouldn’t have to go to that club anymore. He said he liked going there. I asked him if he wasn’t frightened that someone would see him with this Russian and suspect him of spying. Giles collapsed on the bed and muttered something about they might be right if that’s what they suspected. He had been drinking a lot that night – mostly brandy, and I’d noticed before that it affects him in a way other drinks don’t.’

By now Tessa had become very quiet and serious. It was a new sort of Tessa. I’d only known her in her role of uninhibited adventuress. ‘Go on,’ I prompted her.

Tessa said, ‘Well, I still thought he was joking, and I was just making a gag out of it. But he wasn’t joking. “I wish to God I could get out of it,” he said. “But they’ve got me now and I’ll never be free of them. I will end up at the Old Bailey sentenced to thirty years.” I said, couldn’t he escape? Couldn’t he get on a plane and go somewhere?’

‘What did he say?’

‘“And end up in Moscow? I’d sooner be in an English prison listening to English voices cursing me than spend the rest of my life in Moscow. Can you imagine what it must be like?” he said. And he went on all about the sort of life that Kim Philby and those other two had in Moscow. I realized then that he must have been reading up all about it and worrying himself to death.’

Tessa sipped her champagne.

Fiona said, ‘What will happen now, Bernie?’

‘We can’t leave it like this,’ I said. ‘I’ll have to make it official.’

‘I don’t want Tessa’s name brought into it,’ said Fiona.

Tessa was looking at me. ‘How can I promise that?’ I said.

‘I’d sooner let it drop,’ said Tessa.

‘Let it drop?’ I said. ‘This is not some camper who’s trampled through your dad’s barley field, and you being asked if you want to press charges for trespass. This is espionage. If I don’t report what you’ve told me, I could be in the dock at the Old Bailey with him, and so could you and Fiona.’

‘Is that right?’ said Tessa. It was typical of her that she asked her sister rather than me. There was a simple directness about everything Tessa said and did, and it was difficult to remain angry with her for long. She confirmed all those theories about the second child. Tessa was sincere but shallow; she was loving but mercurial; she was an exhibitionist without enough confidence to be an actor. While Fiona displayed all the characteristics of elder children: stability, confidence, intellect in abundance, and that cold reserve with which to judge all the shortcomings of the world.

‘Yes, Tess. What Bernie says is right.’

‘I’ll see what I can do,’ I said. ‘I can’t promise anything. But I’ll tell you this: if I am able to keep your name out of it and you let me down by breathing a word of this conversation to anyone at all, including that father of yours, I’ll make sure you and he and anyone else covering up are charged under the appropriate sections of the Act.’

‘Thank you, Bernie,’ said Tessa. ‘It would be so rotten for George.’

‘He’s the only one I’m thinking of,’ I said.

‘You’re not so tough,’ she said. ‘You’re a sweetie at heart. Do you know that?’

‘You ever say that again,’ I told Tessa, ‘and I’ll punch you right in the nose.’

She laughed. ‘You’re so funny,’ she said.

Fiona went out of the room to get a progress report on the cooking. Tessa moved along the sofa to be closer to where I was sitting at the other end of it. ‘Is he in bad trouble? Giles – is he in bad trouble?’ There was a note of anxiety in her voice. It was uncharacteristically deferent to me, the sort of voice one uses to a physician about to make a prognosis.

‘If he cooperates with us, he’ll be all right.’ It wasn’t true of course, but I didn’t want to alarm her.

‘I’m sure he’ll cooperate,’ she said, sipping her drink and then looking at me with a smile that said she didn’t believe a word of it.

‘How long since he met this Russian?’ I asked.

‘Quite a time. You could find out from when he joined the chess club, couldn’t you?’ Tessa shook her glass and watched the bubbles rise. She was using some of the skills she’d learned at drama school the year before she’d met George and married him instead of becoming a film star. She leaned her head to one side and looked at me meaningfully. ‘There’s nothing bad in Giles, but sometimes he can be a fool.’