По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

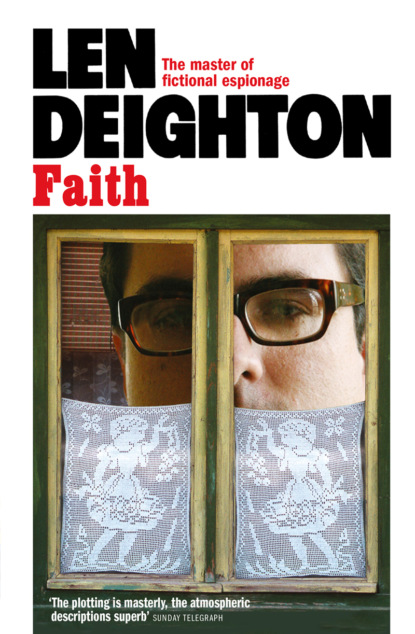

Faith

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I said: ‘A high-velocity missile going through glass, a round from a hand-gun for instance, produces radial fractures and several concentric fractures. In this case there were none. Furthermore the hole made by a bullet produces a powdering of glass around the actual hole. A low-velocity missile, such as a stone, knocks a piece out of the glass leaving a neater smoother edge.’

‘Are you snowing me, Bernard?’ said Dicky, shaking his head to stress his disbelief. Frank looked from one to the other of us, adopting his favourite role of unbiased adjudicator. ‘Is this just your own theory or something out of a home-repairs manual?’

‘Surely, Dicky, every schoolboy knows that glass is a supercooled liquid which, under impact from a fast-moving missile, bends until it fractures in long cracks radiating from the point of impact. It continues bending for a long distance until eventually it makes a second series of cracks concentrically from the point of impact. Also a high-velocity missile makes a quite different type of hole. It fragments or powders the glass as it exits, and this reveals the direction of the missile. The degree of fragmentation usually gives a rough idea of the likely range from which the shot came; the closer the range the heavier the fragmentation.’

Frank smiled.

‘Okay, you clever shit,’ said Dicky. ‘So why didn’t you say the killer definitely was not waiting outside? You didn’t say they weren’t waiting outside did you?’

‘Because the killer might have fired through a hole in the glass that was already there,’ I said.

‘You didn’t say that either,’ he complained.

‘I can’t be sure what I said.’ If proof was needed to tell me I was slipping, my ill-timed lecture about fracturing glass was it. In the old days I would have taken more care when kicking the sand of science into the face of a prima donna like Dicky, especially doing it in the presence of Frank, an old-timer everyone respected, or claimed to. ‘The fact is that I didn’t stick around to find out.’

Dicky had been to Oxford University and come away with an undisputed reputation for cleverness. That reputation had stuck. Cleverness was not measured and quantified in the way that passing exams or rowing strenuously enough to become a blue was on record. Cleverness was a vague characteristic not universally respected by Englishmen of Dicky’s class; it suggested cunning and the sort of hard work and determination that marked the social climber. And so Dicky’s cleverness remained a threat ever present, but a promise still unfulfilled. He looked at me and gave a sour grin. ‘But why cut and run, Bernard? You had a good man with you.’

‘An inexperienced kid.’

‘Fearless,’ said Dicky. This suggested to me that the kid might be one of Dicky’s protégés, some amiable graduate he’d met on one of his frequent bibulous visits to his alma mater. ‘We’ve used him on a couple of previous jobs: utterly fearless.’

‘An utterly fearless man is more to be dreaded as a comrade than as an enemy,’ I said.

Frank laughed before Dicky had absorbed it. In Frank’s hand, along with my brief account of our unsuccessful mission, I could see the report the kid had submitted. In yellow marker I spotted a sentence about me firing the gun. There was some lengthy comment pencilled in the margin. They hadn’t mentioned the gun I collected from Andi. I still had that to come.

Dicky said: ‘This dead colonel – this VERDI – asked for you. What’s this about someone owing someone a favour? What favour did the poor bastard owe you?’

‘They always say that,’ I explained. ‘That’s the standard form when they are seeking a deal with the other side.’

‘When did you last see him?’ said Dicky.

‘I know nothing of him. His asking for me was just a gimmick.’

‘Try and remember,’ said Dicky in a voice that clearly said that he didn’t believe me. ‘He knows you all right.’

‘More to be dreaded as a comrade than as an enemy,’ said Frank, as if committing it to memory, and chuckled. ‘That’s a good one, Bernard. Well, if you can’t remember VERDI maybe we’ll leave it at that. You’ll want to get back to London and see your children. Your wife is joining you there I heard.’

‘That’s right,’ I said.

Dicky shot a glance at me. He didn’t like the way that Frank was letting me off the hook, and I thought for a moment he was going to mention Gloria, the woman I’d been living with during the time I believed my wife was a defector working for the East. ‘Then why is there a seat reserved for Samson on the flight to Zurich?’ Dicky asked.

I got to my feet. ‘Samson’s a common name, Dicky,’ I said, without getting excited.

‘Field agents are all devious.’ Frank smiled and waved a languid hand in the air. ‘It’s the job that does it. How could Bernard be so good at his job without being constantly wary?’

‘Who do you know in Zurich?’ Dicky asked, as if knowing someone in Zurich was in itself a sinister development.

‘My brother-in-law.’ Frank looked at Dicky as if expecting some reaction to this, but Dicky just nodded. ‘He moved there after his wife was killed. I will have to see him eventually … there are domestic affairs that will have to be settled. Tessa assigned property and her share of a trust to Fiona.’

Frank smiled. He knew why I was going to Zurich of course. He knew I would be cross-checking with Werner Volkmann everything the Department had told me. Dicky knew too. Neither of them liked the idea of me talking to Werner, but Frank was rather more subtle and able to hide his feelings.

Dicky had been pacing about and now he turned on his heel and left the room, saying he would be back in a moment.

‘He gave a little party last night at a new restaurant he found in Dahlem. Indian food apparently, and he suspects the bhindi bhaji has upset him,’ Frank confided when Dicky had gone. ‘Do you know what a bhindi bhaji is?’

‘No, I’m not quite sure I do, Frank.’

Frank nodded his approval, as if such knowledge would have alienated us. ‘Did Bret Rensselaer tell you to see Werner in Zurich?’

I hesitated, but the fact that Frank had waited for Dicky to exit encouraged me to confide in him. ‘No, Bret told me to stay away from Werner. But Werner gets to hear things on the grapevine long before we get to know them through our channels. He might say something useful.’

‘Dicky has staked a lot on having VERDI sitting in London spilling his guts to us. VERDI dead means all Dicky’s planning dies with him. He’ll be casting about for someone to blame; make sure it’s not you.’

‘I wasn’t there,’ I explained for what must have been the thousandth time. ‘He was dead when we got there.’

‘VERDI’s father was a famous Red Army veteran: one of the first into Berlin when the city fell.’

‘So everyone keeps telling me.’ I looked at him. ‘Who cares? That was over forty years ago and he was just one of thousands.’

‘No,’ said Frank. ‘VERDI’s father was the lieutenant commanding Red Banner No. 5.’

‘Now you’ve got me,’ I admitted.

‘Well, well! Berlin expert admits defeat,’ said Frank smugly. ‘Let me tell you the story. In mid-April 1945 – as they advanced on Berlin – the 79th Rifle Corps got orders from the Military Council of the Third Shock Army that a red flag was to be planted on top of the Reichstag. And Stalin had personally ordered that it should be in place by May Day. On April 30th, with the deadline ticking, our man and his team of infantry sergeants fought their way up inside the Reichstag building, from room to room, floor to floor, until they climbed up on to the roof and with only four of them still alive, completed their task with just seventy minutes to go before it was May Day.’

‘No, but I saw the movie,’ I said.

‘Make jokes if you like. For war babies like you it may mean nothing, but I guarantee that communists everywhere would have been devastated at the news that the son of such a man – a symbol of the highest peak of Stalinist achievement – would come over to us.’

‘Devastated enough to kill him to prevent it?’

‘That’s what we want to know, isn’t it?’

‘I’ll find out for you,’ I said flippantly.

‘Don’t go rushing off to Switzerland to ask Werner,’ said Frank. ‘You know Dicky; he is sure to have asked the Berne office to assign someone to meet the plane and discreetly find out where you go. Treat Dicky carefully, Bernard. You can’t afford to make more enemies.’

‘Thanks, Frank,’ I said and meant it warmly. But such assurances left Frank unsatisfied, and now he gave me a penetrating stare as if trying to see into my mind. Long ago he had promised my father that he would look after me, and he took that promise seriously, just as Frank took everything seriously, which was what made him so difficult to please. And like a father, Frank was apt to resent any sign that I could have a mind of my own and enjoy private thoughts that I did not share with him. I suppose all parents feel that anything less than unobstructed open-door access to all their offspring’s thoughts and emotions is tantamount to patricide.

Frank said: ‘As soon as Dicky knew that VERDI was dead he said someone must have talked.’

‘Dicky likes to think that people are plotting against him.’

‘Can’t you see the obvious?’ said Frank with an unusual display of exasperation. ‘They haven’t sent Dicky here as a messenger. Dicky is important nowadays. Whatever Dicky thinks will inevitably become the prevailing view in London.’

‘No one talked in London or anywhere else. It’s absurd. They’ll eventually discover their mistake.’

‘Oh no they won’t. The people in London never discover their mistakes. They don’t even admit them when others discover their mistakes. No, Bernard, they’ll make their theories come true whatever it costs in time and trouble and self-delusion.’