The Comic Latin Grammar: A new and facetious introduction to the Latin tongue

Note also. That all nouns of the vocative case are of the second person. So that if we should say, O asine, O thou donkey; or O asini, O ye donkeys, we should have grammar at least on our side.

Be it your care to prevent us from having justice also.

Of the Verb Esse, to beBefore other verbs are declined, it is necessary to learn the verb Esse, to be. And before we teach the verb Esse, to be, it is necessary to make a few remarks on verbs in general.

In the first place we have to observe, that they are rather difficult; and in the next, that if any one expects that we are going to consider them in detail, he is very much mistaken.

But our skipping a very considerable portion of the verbs, is no reason why boys should do the same. Were we all to follow the examples of our teachers, instead of attending to their precepts, where would be the world by this time?

Whirling away, no doubt, far from the respectable society of the neighbouring planets, and blundering about right and left, pell-mell, helter-skelter among the fixed stars – itself, “and all which it inherit” in that glorious state of confusion so admirably described by the poet Ovid —

“Quem dixere Chaos,”

which men have called Shaos. It would indeed be little better than a broken down Shay-horse.

But “revenons à nos moutons,” that is, let us get back to our verbs. We recommend the most attentive and diligent study of all of them as set forth in the Eton Grammar, assisted by that kind of association of ideas, of which we shall now proceed to give a few specimens.

Sum, es, fui, esse, futurus, to be, – or not to be – that is the question.

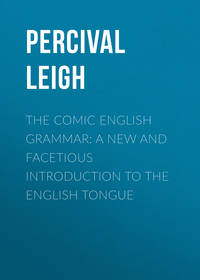

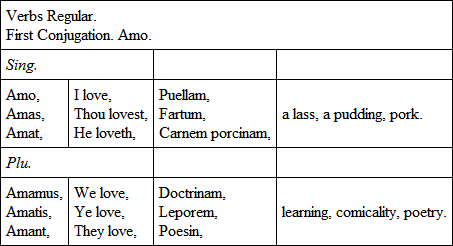

Rule 1. To each person of a verb, singular and plural, join a noun, according to your taste or comic talent. Should you be deficient in the inventive faculty, apply for assistance to one of the senior boys, which, in consideration of your fagging for him, he will readily give you. If yourself a senior boy, apply to the master.

We would proceed in this way with Sum, but that we are afraid of being tire-sum.

The consideration of which three things leads us to

Rule 2. In repeating the different tenses of verbs, be careful to be provided with a short English verse, contrived so as to rhyme with the third person singular, and another to rhyme with the third person plural. In this way your powers of composition as well as of memory will be profitably exercised.

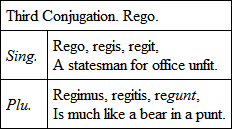

Rule 3. Should you be desired to give the English of each person in the tense which you are repeating, you may (we mean a class of you), follow a plan adopted with great success and striking effect in that kind of dramatic representation entitled “A Grand Opera,” that of singing what you have to say. Hold up your head, turn out your toes, clear your voices, and begin. A-hem!

Are regular bores. The above Rules are equally applicable to them, and also to the

Defective Verbs;Concerning which it may be asserted, that though almost all of them have tenses more or less imperfect, there are some which have not a single Imperfect Tense.

Impersonal VerbsSuch as delectat, it delighteth; decet, it becometh, &c., answer to such English verbs as take the word it before them. When we consider that it is a term of endearment used in speaking to babies, as “it’s a pretty dear,” we cannot help thinking that Verbs Impersonal ought to be pet verbs. Such however, is not, as far as we know, the fact.

OF A PARTICIPLE

A participle is a hybrid part of speech; a kind of mongrel-cross, between a noun and a verb. It is two parts verbs, and four parts noun; wherefore its composition may be likened unto the milk sold in and about London, which is usually watered in the proportion of four to two. The properties of the noun belonging to it, are, number, gender, case, and declension; those of the verb, tense, and signification.

As a horse hath four legs, so hath a verb four participles.

Air. – Bonnets of BlueThere ’s one of the present, – and then,There ’s one of the future in rus;Of the tense preterperfect a third, – and again,A fourth of the future in dus.Participles are declined like nouns adjective, as – but no! how can we ask our fair (blue) readers to decline a-man’s (amans) loving.

Now here we feel called upon to say a few words on the difference between a man’s loving and a woman’s loving. It has often been a question, whether do men or women love most dearly? To us the matter does not appear to admit of a doubt. We defy any of our male readers to be in love (when they are old and silly enough) for six months without finding themselves most grievously out of pocket. We have a friend who was in that unfortunate condition for about a month, and it cost him at least seven and sixpence a week in fees to the maid servant, and that without once being enabled to exchange a word with the object of his affections. At last he began to think that he was paying rather too dear for his whistle; so he gave it up. What girl would have held on so long, and laid out so much money without a return – not of soft affection, but of hard cash? Women, indeed, instead of loving dearly, love, according to our own experience, particularly cheaply. Think of what they save, by taking their admirers “shopping” with them, in ribands, bracelets, and the like, to say nothing of coach-hire, pastry-cooks, and the price of admission, when they go with them to the play. And we should like to hear of the young lady who in these days would dispose of her hand at any thing less than a good round sum if she could help it – no, no. To love dearly is the precious prerogative of the lords of the creation alone.

But we are forgetting our participles.

The participle of the present tense ends in ans, or ens; as Flagellans, whipping; Lædens, hurting.

That of the future in rus, signifies a likelihood, or design of doing something, as Flagellaturus, about to whip; Læsurus, about to hurt.

That of the preterperfect tense has generally a passive signification, and ends in us, as Flagellatus, whipped; Læsus, hurt.

That of the future in dus has also a passive signification, as Flagellandus, to be whipped; Lædendus, to be hurt.

Note 1. All participles are declined like nouns adjective. We recommend the above participles to be declined like winking.

2. There are three things that are not hurt by whipping – a top, a syllabub, and a cream.

OF AN ADVERB

Convex and concave spectacles are contrivances used to increase or diminish the magnitude of objects.

Adverbs are parts of speech used to increase or diminish the signification of words.

Spectacles are joined to the bridge of the nose.

Adverbs are joined to nouns adjective, and verbs. Benè, well; multùm, much; malè, ill, &c. are adverbs.

Cæsar multûm conturbavit indigenas:

Cæsar much astonished the natives.

OF A CONJUNCTION

A conjunction is a part of speech that joineth together; wherefore it may be likened unto many things; for instance —

To glue, to paste, to gum arabic, to mortar, (for it joins words and sentences together like bricks), to Roman cement, (Latin conjunctions more especially), to white of egg, to isinglass, to putty, to adhesive plaster, to matrimony.

Conjunctions are thus used.

Ova et lardum, eggs and bacon. Dimidium dimidiumque, half-and-half. Amor et dementia, love and madness.

OF A PREPOSITION

A Preposition is a part of speech commonly set before another word. Words, however, do not eat each other, though men have been known to eat words. Ab, ad, ante, &c. prepositions.

Sometimes a preposition is joined in composition with another word, as prostratus, knocked down – floored.

Tullius ab aquario prostratus est:

Tully was knocked down by a waterman.

OF AN INTERJECTION

An interjection is a word expressing a sudden emotion or feeling, as Hei! Oh dear! – Heu! Lack-a-day! – Hem! Brute, Hollo! Brutus. – Euge! Tite, Bravo! Titus.

We here find ourselves approaching the delightful subject of the three Concords, with which we shall make short work, first, for fear of further Accidence, and, secondly, because we are no fonder than boys are of repetitions, which, were we to follow the Eton Grammar in the Concords, we should be obliged to make in the Syntax.

However, there are just one or two points to be mentioned.

Rule. (Text-hand copy-books.) “Ask no questions.”

Exception. When you want to find where the concord should be, ask the following —

Who? or what? – to find the nominative case to the verb.

Whom? or what? with the verb, for the accusative after it.

Who? or what? with the adjective, for the substantive to the adjective.

Who? or what? with the verb, for the antecedent to the relative.

But remember, that the use of the interrogatives who? and what? however justifiable in grammar, is very impertinent in conversation. What, for example, can be more ill-bred than to say, Who are you? Indeed, most questions are ill mannered. We do not speak of such expressions as, Has your mother sold her mangle? and the like, used only by persons who have never asked themselves where they expect to go to? but of all unnecessary demands whatever. “Sir,” said the great Dr. Johnson, “it is uncivil to be continually asking, Why is a dog’s tail short, or why is a cow’s tail long.”

OF THE GENDERS OF NOUNS,

Commonly known by the name of“Propria Quæ Maribus.”As the “Propria Quæ Maribus” is no joke, and the “As in Præsenti” is too much of a joke, we must do with them as we did with the verbs. Singing a song is always esteemed a valid substitute for telling a story; and the indulgence which we would have extended to us in this respect, is that universally granted to civilized society.

Let the “Propria Quæ Maribus” be turned into a series of exercises, thus, or in like manner —

Air. – “Here ’s to the maiden of bashful fifteen.”All names of the male kind you masculine call,Ut sunt (for example), Divorum,Mars, Bacchus, Apollo, the deities all,And Cato, Virgilius, virorum.Latin ’s a bore, and bothers me sore,Oh how I wish that my lesson was o’er.Fluviorum, ut Tibris, Orontes likewise,Fine rivers in ocean that lost are,And Mensium – October an instance supplies;Ventorum, ut Libs, Notus, Auster.Latin ’s a bore, &c.We do not pretend that the mode of study here recommended, is perfectly original. The genuine Propria Quæ Maribus, and As in Præsenti, like the writings of the most remote antiquity, consist of certain useful truths recorded in harmonious numbers. It has been a question among commentators, whether these interesting compositions were originally intended to be said or sung. Analogy (we mean that derived from the works of Homer and Virgil) would incline us to the latter opinion, which however does not appear to have been generally entertained in the schools. We shall give one more specimen in the above style; and we beg it may be remembered, that in so doing, we have no wish to detract in any way from the merit of the illustrious poet in the Eton Grammar; all we think is, that he might have introduced a little more comicality into his work, while he was about it.

OF THE PRETERPERFECT TENSE, &c. OF VERBS

Otherwise the “As in Præsenti.”As in Præsenti – Preterperfect – avi,Oh! send me well done, lean, and lots of gravy,Save lavo, lavi, nexo, nexui.Ah! me – how sweet is cream with apple-pie,Juvi from juvo, secui from seco,Could n’t I lie and tipple, more Græco!From neco, necui, and mico, wordWhich micui makes, Oh! roast goose, lovely bird!Plico which plicui gives. Delightful grub!And frico, fricas, fricui, to rub —So domo, tono, domui, tonui make.And sono, sonui. – Lead me to the stake,I mean the beef-stake– crepo, crepui too,Which means to crack (as roasted chestnuts do,)Then veto, vetui makes —forbidding sound,Cubo, to lie along (these verbs confoundYe gods) makes cubui, do gives rightly dedi;What viler object than a coat that ’s seedy? —Sto to form steti has a predilection;Well – let it if it likes, I’ve no objection.&c. &c. &c.SYNTAXIS,

or the Construction of GrammarQ. What part of the grammar resembles the indulgences sold in the middle ages?

A. Sin-tax.

The first Concord;The Nominative case and the VerbWhere there is much personality, there is generally little concord.

However, a verb personal agrees with its nominative case in number and person, as Sera nunquam est ad bonos mores via, The way to good manners is never too late. Mind that, brother Jonathan.

Note– The above maxim is especially worthy of the attention of neophytes in law and medicine; of the gods in the gallery, and of Members of the House.

The nominative case of pronouns is rarely expressed, except for the sake of distinction or emphasis, as —

Tu es exquisitus, tu es,

You ’re a nice man, you are.

Sometimes a sentence is the nominative case to the verb, as

Ingenuas pugni didicisse fideliter artes,

Mollitos mores non sinit esse viri.

The faithful study of the fistic art

From mawkish softness guards a Briton’s heart.

Who can doubt it? But, besides, we have much to say in praise of boxing. In the first place, it is a classical accomplishment. To say nothing of the Olympic and Isthmian Games, which are of themselves sufficient proof of the elegant and fanciful tastes of the ancients; we need only allude to the fact, that the Corinthians are universally celebrated for their proficiency in this science. Then, of its eminently social tendency, there can be no doubt. What can be more conducive to good fellowship, and conviviality than the frequent tapping of claret, attendant both on its study and practice? Nor can its beneficial influence on the fine arts be called in question, seeing that its immediate object is to teach us the use of our hands. And (which perhaps is the most pursuasive argument of all), it is particularly pleasing to the fair sex, who besides their well known admiration of bravery, are, to a woman, devotedly attached to the ring.

Sometimes an adverb with a genitive case stands in the place of the nominative, as —

Partim astutorum mordebantur,

Part of the knowing ones were bit.

We must contend that the above is a racy observation.

Exceptions to the RuleVerbs of the infinitive mood – but hold. Remember that there is scarcely any rule without an exception; and this axiom particularly applies to the Syntax. We used to wish it did not; because then we should not have had so much to learn – to resume however —

Verbs of the infinitive mood often have set before them an accusative case instead of a nominative; the conjunction quod, or ut, being left out, as

Annam reginam aiunt occubuisse:

They say that Queen Anne’s dead.

A verb placed between two nominative cases of different numbers, is not like a donkey between two stacks of hay, it makes choice of one or the other, and agrees with it, as

Amygdalæ amaræ venenum est,

Bitter almonds is poison.

We have written the English beneath the Latin. Perhaps it may be imagined that we think good English beneath us.

A singular noun of multitude is sometimes joined to a plural verb; as

Pars puerorum philosophum secuti sunt,

Part of the boys followed the philosopher.

And so they would now, particularly if they saw one in costume.

Verbs impersonal have no nominative case before them, as

Tædet me Grammatices, I am weary of Grammar.Pertæsum est Syntaxeos, I am quite sick of Syntax.Mirificum visum est Socratem in gyrum saltantem videre,It seemed wonderful to behold Socrates jumping Jim Crow.Adjectives, participles, and pronouns agree with the substantive in gender, number, and case, as

Vir exiguo conventui, sobrioque idoneus:

A nice man for a small tea-party.

The Spartans, probably, were men of this kind; their aversion to drunkenness being well known.

Observe how close the concord is between substantive and adjective. The ties of wedlock are nothing to it; for, besides that in that happy state there is very often not a little discord, it is quite impossible that man and wife should ever agree in gender.

Sometimes a sentence supplies the place of a substantive; the adjective being placed in the neuter gender, as

Audito reginam leones cœnantes visisse:

It being heard that Her Majesty had gone to see the lions at supper.

Third ConcordThe relative and the antecedentThe relative and antecedent hit it off very well together; they agree one with the other in gender, number, and person, as

Qui plenos haurit cyathos, madidusque quiescit,

Ille bonam degit vitam, moriturque facetus.

“He who drinks plenty, and goes to bed mellow,

Lives as he ought to do, and dies a jolly fellow.”

Horace was the fellow for this kind of thing. Cato must have been a regular wet blanket.

Sometimes a sentence is placed for an antecedent, as

Heliogabalus, spiritu contento, viginti quatuor ostrearum demersit in alvum, quod Dandoni etiam longé antecellit.

Heliogabalus, at one breath, swallowed two dozen of oysters, which beats even Dando out and out.

Many of the ancients could swallow a good deal.

A relative placed between two substantives of different genders and numbers, sometimes agrees with the latter, as

Pueri tuentur illum librum quæ Latina Grammatices et Comica dicitur.

Boys regard that book which is called the Comic Latin Grammar.

Sometimes a relative agrees with the primitive, which is understood in the possessive, as

Mirabantur impudentiam suam qui ad reginam literas misit.

They wondered at his impudence, who wrote a letter to the queen.

If a nominative case be interposed between the relative and the verb, the relative is governed by the verb, or by some other word which is placed in the sentence with the verb, as

Luciferi quos Prometheus surripuit, ad Jovem cujus numen contempsit, pertinebant.

The Lucifers which Prometheus shirked, belonged to Jupiter, whose authority he despised.

In fact, Prometheus made light of Jupiter’s lightning.

We now take leave of the Concords, observing only how pleasant it is to see relatives agree.

Our next subject is the

Construction of Nouns SubstantiveWhich is not quite so amusing as the construction of small boats, paper kites, pinwheels, crackers, or any other mode of displaying the faculty of “constructiveness” – though in one sense the construction of nouns substantive, is not unlike the construction of puzzles.

When two substantives of a different signification meet together, the latter is put in the genitive case, as

Ulysses lumen Cyclopis extinxit:

Ulysses doused the glim of the Cyclops.

This genitive case is sometimes changed into a dative, as

Urbi pater est, urbique maritus. – Gram. Eton.

He is the father of the city, and the husband of the city.

He must have been a pretty fellow, whoever he was.

An adjective of the neuter gender, put without a substantive, sometimes requires a genitive case, as

Paululùm honestatis sartori sufficit:

A very little honesty is enough for a tailor.

A genitive case is sometimes placed alone; the preceding substantive being understood by the figure ellipsis, as

Ubi ad magistri veneris, cave verbum de porco:

When you are come to the master’s (house), not a word about the pig.

The word pig is a very general term, and is used to signify not only the animal so called, and such of the human race as resemble him in habits, appearance, or feelings; but also to denote a variety of little things, which it is sometimes necessary to keep secret. A pedagogue now and then discovers a pig-tail appended to his coat collar – this, or rather the way in which it got there, is one of the little pigs in question. Robbing the larder or the garden is another; so is insinuating horse-hairs into the cane, or putting cobbler’s wax on the seat of learning – we mean the master’s stool. A sort of pig (or rather a rat) is sometimes smelt by the master on taking his nightly walk though the dormitories, when roast fowl, mince pies, bread and cheese, shrub, punch, &c. have been slyly smuggled into those places of repose. Shirking down town is always a pig, and the consequences thereof, in case of discovery, a great bore.

Considering that a secret is a pig, it is singular that betraying one should be called letting the cat out of the bag.

Two substantives respecting the same thing are put in the same case, as

Telemachum, juvenem bonæ indolis, Calypso existimavit.

Calypso thought Telemachus a nice young man.

By the way, what a nice young man Virgil makes out Marcellus to have been!

Praise, dispraise, or the quality of a thing is placed in the ablative, and also in the genitive case – as

Vir paucorum verborum et magni appetitûs:

A man of few words and large appetite.

Paterfamilias. Vir multis miseriis:

A father of a family. A man of many woes.

The man of most woes, however, is a hackney-coachman.

Opus, need, and usus, need, require an ablative case, as

Didoni marito opus erat;

Dido had need of a husband.

Æneæ cœnâ usus erat;

Æneas had need of a dinner.

But opus appears to be sometimes placed like an adjective for necessarius, necessary, as

Regi Anthropophagorum coquus opus est:

The King of the Cannibal Islands wants a cook.

Which would serve his purpose best – a valet-de-chambre who dresses men, or a wit, who roasts them?

The Construction of Nouns AdjectiveThe genitive case after the adjectiveAdjectives which signify desire, knowledge, memory, fear, and the contrary to these, require a genitive case, as

Est natura vetularum obtrectationis avida:

The nature of old women is fond of scandal.

This particularly applies to old maids. As those delightful creatures now-a-days, not content with being grey aspire to be actually blue; we cannot help recommending to them a kind of study, for which their propensity to cutting up renders them peculiarly adapted; we mean Anatomy. And since it is on the foulest and most odious points of character that they chiefly delight to dwell, we more especially suggest to them the pursuit of Morbid Anatomy, as one which is likely to be attended both with gratification and success.

Mens tempestatum præscia:

A mind foreknowing the weather.

A piece of sea-weed has often, heretofore, been used as a barometer; but it is only of late that this purpose has been answered by a murphy.

Immemor beneficii:

Unmindful of a kindness.

The sort of kindness one is least likely to forget is that which our master used to say he conferred upon us, when he was inculcating learning by means of the rod. We cannot help thinking, however, that he began at the wrong end.