Method in the Study of Totemism

Consequently Mr. Goldenweizer can make no argumentative use of the alleged local names of the Tlingit clans. If the totemic names of exogamous units – showing connections with totemism in crests and totemic phratry names – be absent, that is because, under known conditions, they have been superseded by local names or nicknames. This process is a vera causa in totemic society.

IX

I now give an American case, in which a tribe, the Mandans, exhibit female descent, exogamous clans, and a mixture of totemic clan names with local names or sobriquets. The people were settled, lived in villages or towns, "with houses very commodious, neat, and comfortable." The tribe was agricultural, growing maize, beans, pumpkins, and tobacco. Out of seven clan names four were totemic – Wolf, Bear, Prairie Chicken, Eagle; two – Flathead and Good Knife – look like nicknames; High Village is local.63 Here we find other sorts of clan names encroaching on totem names.

Among the Crows, with exogamous clans and female descent, out of twelve clan names four are totemic – Prairie Dog, Skunk, Raven, Antelope; three are very unkind nicknames.64

The American tribes have been much disturbed by the whites, and many changes have occurred in their institutions. As Mr. Frazer points out, in a book of 1781 Captain Carver describes Siouan "bands" or "tribes" (really totem kins), each with a badge representing an animal, and named after the animals: Eagles, Panthers, Tigers, Buffaloes, Snakes, Tortoises, Squirrels, Wolves, etc. These people were Sioux or Dacotas; whether they were exogamous or not Carver does not say. But, in place of now bearing totemic names, the "gentes" of these people are at present distinguished by obvious and even odious nicknames, such as "Breakers of the Law," because members of this gens disregarded the marriage law by taking wives within the gens.

So says Mr. Dorsey. Mr. Frazer says the bands of this tribe are not exogamous. But they must have been exogamous when a gens received a nickname for breaking the law of exogamy. One "band" or gens "Eats no Geese"; it may have been a Goose clan. Other bands or gentes bear nicknames or local names.65

I need not give more examples. In America, as in Australia, various conditions, already mentioned, cause changes from totemic names of exogamous clans to local names and nicknames.

It has now been proved that though, in very rare cases, such as those of the Arunta and Narran-ga, sets of people may have totemic names, yet marry within the name; and that, though "clans" may be exogamous and yet bear names which are not totemic, nevertheless the co-existence of totemic names with exogamy prevails in the overwhelming majority of instances, while the exceptions, as they have been accounted for by their causes, prove the rule. Consequently I see no error of method in holding that the totemic name and exogamy are normal features of totemism, while totemism is "an integral phenomenon."

This is my answer to Mr. Goldenweizer's criticisms. Of course I do not say that totemism was the cause of exogamy; I hold that exogamy was prior to totemism, and think it perfectly possible that some exogamous peoples may never have been totemic.

In this discussion I have, not illogically I hope, taken into account relative conditions of advancement among the peoples studied. I have not here shown that reckoning descent in the male line is a social advance on reckoning in the female line, but I am able to prove that it is, at least in Australia. I have shown that wealth, rank, and settled habitations tend to modify totemism, for example, by introducing heraldry, and enabling non-totemic to supersede, now more now less, the totemic names of exogamous units.

Mr. Goldenweizer, as we saw, writes "that these conditions are due to the fact that the tribes of British Columbia are 'advanced' cannot be admitted."66 I am sorry that he cannot admit what is true and obvious. The wealth, the art, the degrees of rank, the settled houses and towns of the British Columbian tribes have introduced the perplexities of their heraldry; as in other parts of America and in Australia other causes have brought in local names for exogamous kins.

1

Journal of American Folk-Lore, April-June, 1910.

2

J. A. F. p. 280

3

Secret of the Totem, p. 28.

4

J. A. F. p. 281.

5

J. A. F. p. 287.

6

J. A. F. p. 183.

7

But I exclude from my treatment of the subject, the "Matrimonial Classes," or "sub-classes" of many Australian tribes, for these are peculiar to Australia, appear to be results of deliberate conscious enactment, and, though they bear animal names (when their names can be translated), have no traceable connection with totemism.

8

J. A. F. p. 182.

9

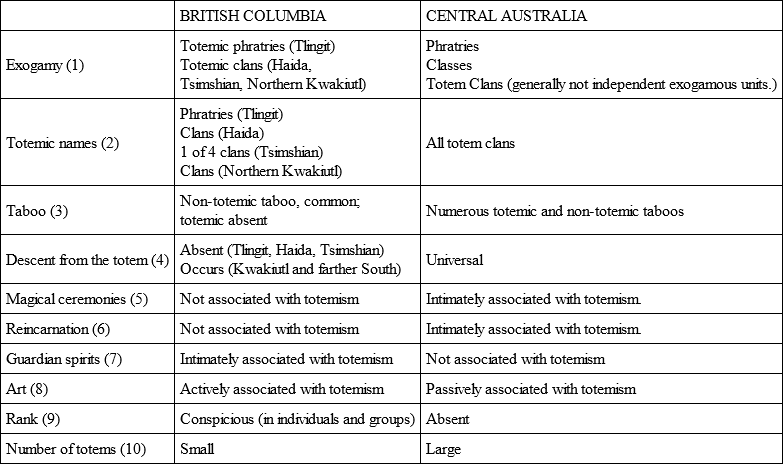

J. A. F. p. 229. I give the tabular form in this note:

TOTEMISM IN BRITISH COLUMBIA AND CENTRAL AUSTRALIA

10

Franz Boas, Fifth Report of the Committee on the North-Western Tribes of Canada, p. 32, cited in Totemism and Exogamy, vol. iii. p. 319, note 2; cf. p. 321.

11

Totemism and Exogamy, vol. iii. pp. 309-311.

12

F. G. Speck, Ethnology of the Yuchi Indians, Philadelphia, 1909, pp. 70 sq. Totemism and Exogamy, vol. iv. p. 312, cf. vol. iii. p. 181.

13

That is, the matrimonial classes, eight in all, are divided into two sets of four each, but these sets are nameless.

14

L. A. Morgan, League of the Iroquois, pp. 79-83.

15

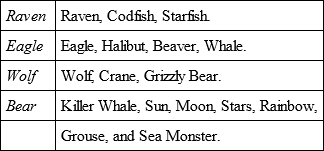

I may be permitted to note that these four Tsimshian clans look, to me, as if they had originally been two pairs of phratries. We find a parallel Australian case in the Narran-ga tribe of York's peninsula in South Victoria. Here Mr. Howitt gives us the "classes" (his term for phratries):

Each of these four main divisions had totem kins within it, and, as usual, the same totem (all are animals) never occurred in more than one main division. (Howitt, N.T.S.E.A. p. 130.) In precisely the same way "crests" of animal name occur in each of the four Tsimshian "clans":

These "crests," thus arranged, no crest in more than one clan (or phratry?) look like old totems in the two pairs of clans, or, as I suspect, of phratries. The Australian parallel corroborates the view that the Tsimshian "clans" have been phratries.

16

J. A. F. p. 187. quoting "Swanton 26th B. E. R., 1904-1905, p. 423."

17

Ibid. p. 229.

18

The truth seems to be that Mr. Goldenweizer (p. 189) misquotes Mr. Swanton, who (26th B. E. R. p. 423) is speaking, not of the Tsimshian but of the Haida. In his p. 190 Mr. Goldenweizer is quoting Dr. Boas, Annual Archaeological Report, Toronto, 1905, pp. 235-249.

19

Thomas, Kinship and Marriage in Australia.

20

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 266, note 1.

21

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 266, note I.

22

Secret of the Totem, pp. 164-170

23

J. A. F. p. 186.

24

J. A. F. p. 190.

25

J. A. F. pp. 190-225.

26

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 266, note 1.

27

Quoted, T. and E., vol. iii. p. 281.

28

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 283.

29

Ber. Eth. Report, 1904-1905, pp. 400-407.

30

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 266.

31

J. A. F., p. 287.

32

R. B. E., ut supra, p. 415.

33

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 268.

34

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 269.

35

R. B. E. ut supra, p. 398.

36

Mayne, Four Years in British Columbia, p. 257 sq. 1862.

37

See T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 309-311.

38

T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 309-311.

39

T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 318, 319.

40

Fifth Report on N. W. Tribes of Canada, 1890. T. and E., vol. iii. p. 320, note 1.

41

Twelfth Report on N. W. Tribes of Canada, 1898, p. 676. T. and E., vol. iii. p. 320, note 1.

42

T. and E., vol. iii. p. 332, citing Dr. Boas in Fifth Report on N. W. Tribes of Canada, p. 33, 1889.

43

It seems to me impossible to suppose that the village community was ever anywhere "the original social unit." – A. L.

44

Rep. U.S. Nat. Museum, 1897. pp. 334-335.

45

J. A. F. pp. 269, 270.

46

Secret of the Totem, p. 125.

47

Secret of the Totem, p. 23.

48

Native Tribes of South-East Australia, p. 153.

49

T. and E., vol. iv. pp. 3, 4.

50

What, follows I have already said in Anthropos, 1910.

51

Northern Tribes, p. 175.

52

Vol. i. pp. 189-190. Central Tribes, p. 123.

53

Central Tribes, p. 123.

54

The myth is self-contradictory in the case of the Achilpa. They were in both phratries; the other totems were confined to one or the other phratry. In the latter case the myth exaggerates the present state of things, and puts all, not the great majority, of each totem in one phratry or the other. In the former case the myth throws the actual state of things back into the past.

55

By "moiety" the authors mean one of the two main exogamous divisions or phratries.

56

Central Tribes, p. 120. In fact out of three Achilpa or Wild Cat sets of wanderers, two, in the legend, are exclusively of one phratry – Purula-Kumara – and one is exclusively of the other, Bulthara-Panunga, op. cit. p. 120.

57

Central Tribes, p. 120.

58

T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 9, 287.

59

T. and E., vol. iii, p. 243.

60

T. and E. vol. iii. p. 245. note 5, citing Washington Matthews. J. A. F. iii., 1890, p. 105, and Navaho Legends, p. 31, 1897.

61

Secret of the Totem, pp. 114, 115.

62

Howitt, N.T.S.E.A., pp. 124, 130, 258, 259.

63

T. and E., vol. ill. pp. 135, 136. Morgan, Ancient Society, p. 158.

64

T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 153, 154.

65

T. and E., vol. iii. pp. 86, 87. Dorsey, R.B.F., xv. (1897) et seq.

66

J. A. F. p. 287.