Method in the Study of Totemism

From all this it appears that Dr. Boas believes the Kwakiutl proper to have been once, "on the maternal stage," of which the usual "relics" survive, but why should all such traces survive? Some must disappear, otherwise there could be no transition!

Apparently, in the village communities, the existence of a mythical ancestor, not ancestress, is postulated; while in the northern tribes, with female descent, mythical ancestresses are postulated. But if, among the Kwakiutl proper, male ancestry is now the recognised rule (and it dimly seems to be so), then, as usual, Kwakiutl myth will throw back into the unknown past the institutions of their present state, will say "ancestor," not "ancestress." No argument can be based on traditions which are really explanatory conjectures. There is advanced no valid reason for supposing that the Kwakiutl proper began with descent in the female line, then advanced to the male line, and then doubled back on the female line, and so evolved transmission of crests in the female line, through husbands.

The waverings of the Kwakiutl between the two lines of descent are, in fact, such as we expect to occur when a people has retained, like the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshians, the system of female descent after reaching a fair pitch of physical culture, and arriving at wealth, rank, and the attribution of children to the paternal stock.

VI

I now come to give my own opinion as to the ways in which Kwakiutl totemism may have attained its existing peculiarities. It is necessary first to defend my view that the essential thing in totemism – surveying the whole totemic field – is the existence of exogamous kins bearing animal and other such names. Here Mr. Goldenweizer opposes me, saying that "no particular set of features can be taken as characteristic of totemism, for the composition of the totemic complex is variable, nor can any particular feature be regarded as fundamental, for not one of the features does invariably occur in conjunction with others; nor is there any evidence to regard any other feature as primary in order of development, or as of necessity original psychologically."45

I have already remarked that this is true; we find human associations, which are not kins or clans, bearing animal and other totemic names, while these associations are not exogamous (the Arunta nation); and we find exogamous sets, kins, or associations which do not bear animal names.

But the co-existence of the exogamous kin with the totemic name of that kin is found in such an immense and overwhelming majority over every other arrangement; the exogamous "totem clan" is so hugely out of proportion in numbers and width of diffusion over the Arunta animal-named non-exogamous associations and other rare exceptions, that we have a right to ask – Are not the exceptions aberrant variations? Have not the Arunta, with non-exogamous sets bearing totemic names, and other peoples with exogamous sets not of totemic names, passed through and out of the usual stage of animal-named exogamous kins? A mere guess that this is so, that the now non-exogamous human sets with totem names have once been exogamous, would be of no value. I must prove, and fortunately I can prove, that it was so.

It is certain, historically, that some exogamous units which now bear non-totemic names, in the past were ordinary totem kins with totemic names. As we can also demonstrate to a certainty that the Arunta have been in, and, for definite reasons, have passed out of, the ordinary stage of exogamous totem kins, we have a right, I think, to say that, normally, the feature of the totemic name is associated with the feature of exogamy, and that the exceptions really prove the rule, for we can show how the exceptions came to vary from the rule.

Mr. Goldenweizer, in a very brief criticism of my own theory of Totemism, given by me in Social Origins (1903), and in The Secret of the Totem (1905), writes "Why is the question, How did the early groups come to be named after the plants and animals? – the real problem? Would not Lang admit that other features may also have been the starting point?" (I not only admit but insist that "other features" were among the starting-points of exogamous totemism.) Among "the other features" Mr. Goldenweizer gives "animal taboos, or a belief in descent from an animal, or primitive hunting regulations, or what not? I am sure that Lang, who is such an adept in following the logos, could without much effort construct a theory of totemism with any one of these elements to start with – a theory as consistent with fact, logic, and the mind of primitive man, as is the theory of names accepted from without."

Now as to the last point, I have written "unessential to my system is the question how the groups got animal names, as long as they got them and did not remember how they got them" (et seq.)46 I did show how European and other village groups obtained animal names, namely as sobriquets given from without; and I proved the same origin of the modern names of Siouan "gentes," of two Highland clans; of political parties, religious sects; and so forth.

This mode of obtaining names is a vera causa: that is all: and nobody had remarked on it, in connection with totemism.

Next I cannot "without much effort" (or with any effort) construct a theory of totemism out of (1) "animal taboos." They are imposed for many known and some unknown reasons, and not all totem kins taboo the totem object. Next (2) as I must repeat that "belief in descent from an animal," is only one out of many post-totemic myths explanatory of totemism; I cannot possibly use it as the starting-point of totemism. If Mr. Goldenweizer has read the book which he is criticising, he forgets that I wrote47 "it is an error to look for origins in myths about origins," and that I refused to accept as corroboration of my theory an African myth which agrees with my own view.

As to (3) "primitive hunting regulations," Mr. Goldenweizer does not tell us what they were. It is a very common "regulation" that no totem kin may hunt its own totem animal, but to suggest that the totem kin was created by the regulation is to mistake effect for cause.

Finally (4), who can take "or what not" for the starting-point of an investigation? But every totem kin has a totemic name: if there is no totemic name how can we know that we have before us a totem kin? If the Tlingit "clans" be exogamous but not named by totemic names (as Mr. Swanton tells us), then the Tlingit clans are not totemic, now, whatever they may have been in the past: and we are not concerned with them.

Of every totem "clan" the totem name is a universal feature; and therefore I must begin my study from what is universal – the names. Here (though we must not appeal to authority), I have the private satisfaction of being in agreement with Mr. Howitt. The assumption by men of the names of objects "in fact must have been the commencement of totemism," says Mr. Howitt.48

I start then, from the totemic names because, – no totemic name, no totemic "clan"! With the totemic name of a social unit in the tribe, I couple exogamy, (though exogamy may exist apart from totemism), because exogamy is always associated with a "clan" of totemic name, except in a very few cases of which the Arunta "nation" is much the most prominent. But it is not to the point, for the Arunta have no totemic clans. Mr. Frazer's latest definition of totemism is "an intimate relation which is supposed to exist between a group of kindred people on the one side and a species of natural or artificial objects on the other…"49 Now the Arunta associations of animal names are not (I must keep repeating) kindreds, are not "clans," are not composed of persons who are, "humanly speaking," akin. The totem is not inherited from either parent or through any kinsman or kinswoman. The Arunta bearers of the same totem name, in each case, do not constitute a "clan." This puts the so-called Arunta "totem clans," non-exogamous, out of action as proofs that "totem clans" may be non-exogamous.

Moreover, the non-exogamous Arunta associations bearing totemic names have once been exogamous totem clans. The usages of the Arunta, and their traditions, and the actual facts of their society, prove that their totems were originally hereditary and exogamous.50

I use the word "prove" deliberately; the demonstration is of historical and mathematical certainty. These facts compel me to believe that the Arunta have been in and passed out of normal hereditary totemism, in which the totems are arranged so that no totem occurs in both main exogamous divisions, and all totems are exogamous. In that normal totemic stage the Arunta have at one time been. But they have passed out of it into their present "conceptional" totemism, with the same totems appearing in both main exogamous divisions, the totems being non-hereditary, and non-exogamous.

Spencer and Gillen say, "in the Arunta, as a general rule, the great majority of the members of any one totemic group belong to one moiety of the tribe, but this is by no means universal, and in different totemic groups certain of the ancestors are supposed to have belonged to one moiety and others to the other, with the result that of course their living descendants also follow their example."51 (This statement I later compare with others by the same authors.) Now in normal totemism, not "the great majority," but all the members of any one totemic group belong to one or other moiety of the tribe. The totems being hereditary, they cannot wander out of their own into the other phratry, and, as all persons must marry out of their own phratry, they cannot marry into their own totem, for no person of their own totem is in the phratry into which they must marry.

At present "the great majority" of members of each totem, among the Arunta, are in one phratry or the other. Thus their society is either, (1) in some unknown way, rapidly approximating itself to normal totemism, or (2) has comparatively recently emerged from normal totemism. The former alternative is impossible. Each Arunta obtains his or her totem by sheer chance, by the accident of the supposed locality of his or her conception, and of the totemic erathipa or ratapa which alone haunt that spot.52 Manifestly this present Arunta mode of determining totems cannot introduce the great majority of each totem into one or the other phratry or main exogamous division (Panunga-Bulthara and Purula-Kumara), for these divisions have now no local habitation or limits. Consequently the arrangement by which the great majority of each totem is in one or the other moiety can be due to nothing but the fact that the Arunta have comparatively recently emerged from normal exogamous and hereditary, into conceptional, casual, non-hereditary and non-exogamous totemism. Had they emerged long ago, and adopted their present fortuitous method of acquiring the totem, manifestly the totems, by the operation of chance, would now be present in almost equal numbers in both phratries. This would also be the case had Arunta totemism always been conceptional and fortuitous.

According to Spencer and Gillen, "it is the idea of spirit individuals associated with churinga and resident in certain definite spots, that lies at the root of the present totemic system of the Arunta tribe."53

This is certainly true; and the facts prove, we shall see, to demonstration, that this actual "conceptional" state of Arunta totemism is later than, and has caused the disappearance of the normal hereditary exogamous totemism, among the Arunta.

It is plain and manifest that if the Arunta nation, from the first, were in their present stage of "conceptional totemism" – the totem of each individual being always determined by sheer chance – when the exogamous division of the tribe was instituted, individuals of each totem would be almost equally distributed between the two main divisions, Purula-Kumara and Bulthara-Panunga. Chance could not put the great majority of the members of every totem name either into one exogamous division or the other. If any one doubts this, let him take four packs of cards (208 cards), and deal them alternately five or six times to two friends, Jones representing the phratry Bulthara-Panunga, and Brown standing for the phratry Purula-Kumara. It will not be found that Brown always holds the great majority of Court cards – Ace, King, Queen and Knave – and the great majority of tens, nines and eights: while Jones holds the great majority of sevens, sixes, and fives, fours, threes, and twos.

Chance distribution does not keep on working in that way; and the chance conceptional distribution of totems could not put the great majority of, say, Kangaroos, Hachea Flowers, Wild Cats, and Little Hawks in the Bulthara-Panunga phratry, and the great majority of Emus, Lizards, Wichetty Grubs, and Dogs in the Purula-Kumara division. That is quite impossible. Yet all (or almost all) Arunta totems are thus distributed between the two main exogamous divisions.

When once the reader understands this fact – insisted on by Spencer and Gillen – he becomes convinced, becomes mathematically certain that the chance distribution of conceptional totemism did not and could not thus array the totems of the Arunta. This present arrangement, and this alone, makes the Arunta associations with totemic names non-exogamous. I proceed to give further evidence of Spencer and Gillen. "Whilst every now and then we come across traditions, according to which, as in the case of the Achilpa," (Cats) "the totem is common to all classes54 we always find that in each totem one moiety of the tribe predominates,55 and that, according to tradition, many of the groups" (totem groups) "of ancestral individuals consisted originally of men or women or of both men and women, who all belonged to one moiety. Thus in the case of certain Okira or Kangaroo groups we find only Kumara and Purula; in certain Udnirringita or Wichetty Grub groups we find only Hulthara and Panunga, in certain Achilpa or 'Wild Cat' (groups) 'a predominance of Kumara and Purula, with a smaller number of Bulthara and Panunga.'56 At the present day no totem is confined to either moiety of the tribe, but in each local centre we always find a great predominance of one moiety, as for example at Alice Springs, the most important centre of the Wichetty Grubs, amongst forty individuals, thirty-five belong to the Bulthara and Panunga and only five to the other moiety of the tribe."57

Here the great majority – thirty-five to five – of the members of the totem belong to one of the two main exogamous divisions. Outside of the Arunta nation and Kaitish all the Grubs would belong to one main exogamous division. It is mathematically certain that chance could not bring thirty-five to five members of a given totem – or, "a great majority" in each case – into one or other phratry.

Consequently the chance distribution of totems on the present conceptional Arunta system has not caused this uniform phenomenon. It follows that the totems of the Arunta were at one time hereditary, and were arranged, some exclusively in one, some exclusively in the other moiety, so that no person could marry into his or her own totem. The fortuitous system of conceptional distribution then arose out of the Arunta philosophy of spirits and emanations, and out of the churinga nanja usage, and has now detached a small minority of members of each totem from their original phratry and lodged them in the other. Members of every totem can therefore find legal spouses of their own totem in the phratry not their own, and may marry them. And thus these Arunta associations with totemic names are now non-exogamous. But they have been exogamous totem kins. Mr. Frazer finds what he calls totemism without exogamy in parts of Melanesia.58 I need not here repeat my arguments, given in Anthropos, vol. v. (1910) pp. 1092-1108, to prove that the so-called "totems" in this case are only animal or vegetable "familiars" of individuals. Thus the great example of "totem clans" so-called, without exogamy, is put out of action. The Arunta "clans" are not clans, and the Arunta have had exogamous totem clans like other people.

VII

We now turn to cases in which exogamous "clans" bear, not totemic names, but local or descriptive names, like the Tlingit according to Dr. Swanton. In several instances it is easy to prove that exogamous "clans," now bearing local or other descriptive names, have previously borne totemic names. This result has often been attained by the circumstance that with male descent of the totem name, a regular local clan is formed. Such a clan then comes to be known by a territorial description (just as lairds were in Scotland) and the totemic name may drop out of use. If so, the clan becomes exogamous under a territorial or other name, and is no longer a totem clan.

But this explanation cannot apply to the Tlingit, with female descent, for with female descent, unless the men go to the women's homes, no local clan of descent is possible. I have shown that I do not pretend to know precisely what are the facts of the Tlingit system, as accounts contradict each other. But in other American cases, as in those of the Apaches and Navahos, the tribes "are divided into a large number of exogamous clans with descent in the female line, but the names of the clans appear to be local, not totemic…"59 Such names are Lone Tree, Red Flat, House of the Cliffs, Bend in a Canyon, and so forth. Are such names inherited? Is every child of a woman of Red Flat called "Red Flat"? Persons of the same clan or phratry (from eight to twelve phratries) may not intermarry. The phratries "have no formal names"; speaking of his phratry a man will often refer to it by the title of its oldest or most numerous clan – and that, it seems, is always a local name, "Dr. Washington Matthews," says Mr. Frazer, "who spoke with authority on the subject, was of opinion that the Navahos clans were originally and indeed till quite recently local exogamous groups and not true clans." What else can they be? But Dr. Washington Matthews found a legend which suggests that the Navahos were once totemic. If this be an explanatory myth its point is to explain why the clans have now local names, and why do the clans think that the fact needs explanation? " It is said that when they set out on their journey each clan was provided with a different pet, such as a bear, a puma, a deer, a snake, and a porcupine, and that when the clans received their local names these pets were set free."60 That is, place-names ousted totem names.

It appears to me that when a tribe acquires settled habits and lives in villages, territorial names may oust totem names, and exogamy may become, as among the Navaho, local, just as it becomes local in several Australian tribes with male descent. But nothing in my theory compels me to suppose that every people has passed through totemic exogamy. Exogamy, in my view, was prior to totemism; totem names were a later way of designating local groups which were already exogamous.61 "The rule would be, No marriage within the local group." The totemic names were a later addition, and I can think of no reason why all peoples should necessarily accept totemic names; only, as it chances, the enormous majority among the lower races have done so.

Perhaps the Navaho and Apaches never had totemic names for their exogamous local groups. They are not known to exhibit any sign or vestige of totemism beyond the legend or myth of the wild animal pets.

All such cases of exogamous units bearing non-totemic names, in tribes of female descent, where no vestige of totemism is found, are outside of the field of totemism. Why should we treat people as totemic who have no totems? If we held the opinion that totemism was the cause of exogamy, the position would be different. At one time I thought that the totem and the totem blood taboo, clinched, as it were, and sanctified a pre-existing exogamy. But as I never found that marriage within the totem was automatically punished by sickness or death; (as, in many tribes, the offence of eating the totem is supposed to be); I saw that marriage within the totem was a breach of secular law, punished capitally by "the State." There is no taboo in the case. But as we repudiate the opinion that totemism was the cause of exogamy, in studying totemism we have no concern with peoples who are exogamous but show no trace of having ever been totemic.

VIII

The case of the Tlingit is quite different. Here the phratries have totemic names; the "clans" in the phratries are said, by early authorities, to have totemic names; the "crests" (mainly the same animals as those said to give names to the Tlingit "clans") are readily to be explained by totemism evolving into heraldry.

But, if the Tlingit clans have not totemic names, then it would appear that, among a people of dwellers in towns, local names of local groups have succeeded to totemic names of totemic kins. This can only occur where people have settled habitations, towns or villages, or where totem kins have been localised by male descent.

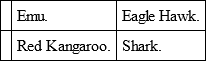

We know that, even among some of the Australian tribes with male descent, totem kins become local groups, and thus the predominant totem of each such group becomes attached to a locality, as among the Narran-ga of Yorke Peninsula. They had two pairs of phratries of animal names:

In each such phratry was a number of totem kins, the same totem never appearing in more than one phratry (or "class" in Mr. Howitt's term). Each class or phratry was limited to a certain territory: Emu to the north, Red Kangaroo to the east, Eagle Hawk to the west, and Shark to the extreme point of the peninsula (south). The totems, passing from father to son, were thus localised. They ceased to be exogamous – obviously because each man, to find a wife eligible on exogamous principles, had to travel to a place inconveniently remote. Thus the only restriction on marriage was "forbidden degrees" of consanguinity.62

All this is easily intelligible. Male descent fixed phratries and totems to localities. By the old rule, if Emu phratry had to marry into Shark phratry, the localities were at the extreme ends of the peninsula, north and south; the other two phratries were as far asunder as the cast of the peninsula is from the west. Consequently, though the old machinery of exogamy existed, the practice of exogamy was dropped: persons might marry within their own totem kins. But we are not told whether all four "classes" inter-married, or each "class" only with one other, because the old rule had fallen into disuse before the coming of Europeans.

Mr. Howitt gives a case of "the transfer of the prohibition of marriage within the totem, to the totem clan – that is, to the locality." In this case, that of the Narrinyeri, with male descent, most "clans" have a local name, or a nickname, and have totems. But three such units or "clans" out of twenty retain their totem names – Whale, Coot, Mullet – thus indicating that totemic preceded local names. A local "clan" may have as many as three totems, but in thirteen cases out of twenty each local clan had but one totem. Among nicknames are "Gone over there," and "Where shall we go?" These clans (thirteen out of twenty) having local names, were strictly exogamous. So also, of course, were the totems of the local clans; though, save in three cases, the name of the place of residence, or a nickname, had superseded the totem name as the title of the clan. It is as if, in place of speaking of the MacIans, we said "the Glencoe men"; instead of speaking of the Stewarts, said "the Appin men"; in place of speaking of the Camerons, said "the men of Lochaber."

Thus it by no means follows that if the exogamous "clans" of any tribe of the North-West Pacific have local names, therefore they never had totemic names, as many of them have to this day. The rise of settled towns or village communities yields a new set of conditions, and a new set of non-totemic names for the clans, in some cases; precisely as the localisation of a totem clan through the operation of male descent causes a local name to take the place, usually but not universally, of a totem clan name in Southern Victoria.