Method in the Study of Totemism

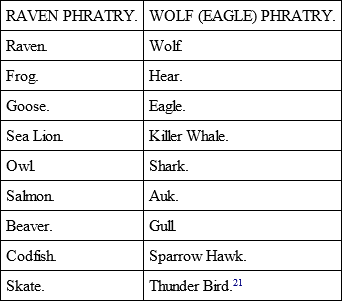

For purposes of comparison with other British Columbia tribes, I give the list of Tlingit totem kins furnished by Mr. Frazer, "on the authority of Mr. F. Boas"20:

Примечание 121

As I found out, and proved, in many Australian tribes the name of each phratry also occurs as the name of a totem kin in the phratry; so also it is among the Tlingit —teste Mr F. Boas.22

Thus on every point – female descent, animal-named phratries, animal-named totem kins, and each phratry containing a totem kin of its own name, the Tlingit totemism is absolutely identical with that of many South-Eastern Australian tribes of the most archaic type.

But the Tlingit, unlike the Australians, live in villages, and "the families or households may occupy one or more houses. The families actually take their names from places." (I italicise the word "families.") Mr. Frazer's authorities here are Holmberg (1856), Pauly (1862), Petroff ("the principal clans are those of the Raven, the Bear, the Wolf, and the Whale"), Krause (both here undated). Dr. Boas (1889). and Mr. Swanton (1908).

Mr Goldenweizer23 does not mention that the "clans" of the Tlingit have animal names. Quite the reverse; he says that "the 'clans' of the Tlingit … bear, with a few exceptions, names derived from localities."24 This is repeated on p. 225.

At this point, really, the evidence becomes unspeakably perplexing. Mr. Frazer, we see, follows Mr. F. Boas and Holmberg (1856) in declaring that the "clans" of the Tlingit bear animal names. Mr. Goldenweizer says that, "with few exceptions," the "clans" of the Tlingit bear "names derived from localities."25 Mr. Goldenweizer's authority is "Swanton, Bur. Eth. Rep., 1904-1905 (1908), p. 398." Mr. Frazer26 also quotes that page of Mr. Swanton, but does not say that Mr. Swanton here gives local, not animal, names to the clans of the Tlingit. Mr. Frazer also cites Mr. Swanton's p. 423 sq. Here we find Mr. Swanton averring that Killer Whale, Grizzly Bear, Wolf, and Halibut are in the Wolf phratry, "on the Wolf side," among the Tlingit; while Raven, Frog, Hawk, and Black Whale are on the Raven side. Here are animal names (not precisely as in Mr. Boas' list) within the phratries. But Mr. Swanton does not reckon these animal names as names of "clans"; to "clans" he gives local names in almost every case. To his mind these animal names in Tlingit society denote "crests" not "clans" and with crests we enter a region of confusion.

I cannot but think that the confusion is caused (apart from loose terminology) by the crests of these peoples. The crests are an excrescence, a heraldic result of wealth and rank; and as such can have nothing to do with early totemism. Scholars sometimes say "totems" when they mean "crests" (and perhaps vice versa), and confusion must ensue.

I quote, on this point, a letter which Mr. Goldenweizer kindly wrote to me (Jan. 21, 1911).

"Since the appearance of Mr. Swanton's studies of the Tlingit and the Haida there remains no doubt whatever that the clans of these two tribes bear (with some few exceptions) names derived from localities. On pp. 398-9-400 of his Tlingit study (26th Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1904-5) he gives a list of the geographical groups, and of the clans with their local names, classified according to the two phratries: Raven and Wolf. It must be remembered that to many of these clans he gives the totems [crests] of the Tlingit phratries: then the gentes [clans] of the Stikin tribe are enumerated. Some of the native names are translated as house or local names; it is pointed out that the raven occurs four times as the crest of four gentes [clans] with different names which, therefore, cannot mean 'raven.'

"The Haida case is quite parallel. Here 'each clan [phratry] was subdivided into a considerable number of families [clans] which generally took their names from some town or camping-place.' And again: 'It would seem that originally each family occupied a certain place or lived in a certain part of a town' (Swanton, The Haida, pp. 66, sq.) Now, of course, many clans are represented in several districts. Opposite p. 76 we find a genealogical table of the Raven families [clans] descended from Foam Woman, with their local names. A similar table of the Eagle families [clans] descended from Greatest Mountain, is given on p. 93. Again Professor Boas' account, although fragmentary, is correct. 'The phratries of the Haida are divided into gentes [clans] in the same way as those of the Tlingit, they also take their names, in the majority of cases, from the houses' (R.B.A.A.S., p. 822). The names of the Skidigate-village-people clans are given as an example.

"As to personal names among the Haida, a curious fact must be noted. Notwithstanding the greater prominence of crests and art among the Haida, their personal names are but seldom derived from animals, as is the rule among the Tlingit, the clans are not now restricted to one village district, but are found in several of the geographical groups. Thus the G ā n A x Á d î (of the Raven phratry) are found in the Tongas, Taku, Chilkat and Yakutat groups, while the Tégoedî (of the Wolf phratry) occur in the Tongas, Sanya, Hutsnuwù and Yakutat groups. The only non-local clan-names in the list are the Kuxînédî (marten people) of Henya; the SAgutēnedî (grass people) and NēsÁdî (salt-water people) of Kake; the LlūklnAxAdî (king-salmon people) of Sitka; and the LugāxAdî (quick people) of Chilkat. Each of these five clans occurs only once in the list, from which we may perhaps infer that they are of relatively late origin (this merely as a suggestion). On the other hand, 'the great majority of Tlingit personal names,' Mr. Swanton tells us, 'referred to some animal, especially that animal whose emblem was particularly valued by the clan to which the bearer belonged' (Bureau, 1904-5, pp. 421-2). In the passage you note, viz. 'the transposition of phratries is indicated also by crests and names, for the killer-whale, grizzly bear, wolf, and halibut, are on the Wolf side among the Tlingit and on the Raven side among the Haida, etc.,' the animals cited are the 'crests' while the 'names' referred to are, of course, the personal names which are derived from animals and as a rule change with the crests; therefore, they are not illustrated in the passage.

"Professor Boas' list is incomplete but similar in substance (Reports of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1889. p. 821). First majority of Haida personal names refer to the potlatch, property, etc. (Swanton, The Haida, pp. 119-120.) This is, no doubt, due to the influence of the potlatch which is among these people the central social and ceremonial feature.

"Holmberg's work I did not see. Probably his list of animals also stands for the crests and not the clan names…

"Of the Tsimshian clans only two bear animal names. K'anhada and GyispotuwE'da do not, as Professor Boas formerly supposed, mean 'raven' and 'bear' (cf. R.B.A.A.S., 1889. p. 823 and Annual Archaeological Report, Toronto, 1906, p. 239)."

If I may ask a question about this very perplexing state of affairs, I would say, Is the animal crest of each "clan" supposed to be later than the local designation of the clan? To me it seems that the crest is in origin a heraldic representation of the clan totem, and that, as in Australia, totemic names of clans are older than names derived from localities or "houses." The house, the fixed building, is part of a society later than the first bearing of totemic names by clans. The crest, as a badge of rank and wealth, is later than the totem; social advance, houses, towns, heraldry, as a mark of rank, appear to me to cause the perplexities, and to place these American tribes outside of the totemism of people without rank, wealth, and houses and heraldry.

As I understand the case, the Tlingit clans did not originally, as Dr. Swanton seems to suppose, "occupy a certain place or live in a certain quarter of a town," whence they derived the place-names or town-names which they at present bear, according to Dr. Swanton. The Tlingit, now living in towns, and with clans of town-names, may naturally fancy that from the first their clans bore local or town-names. But society that begins in people who, like the Tlingit, have female descent, cannot form a local clan of descent, unless the men go to the homes of the women, which is not here the case. Originally I think their crests, as in Holmberg's report, were effigies of their clan totems, and the clans bore their totem names. But with advance to wealth, houses, and settled conditions, the local or town-names (as in other cases is certain) superseded the totem names of the clans, while the totem badge became, as the crest, a factor in a system of heraldry, to us perplexing. Certainly the facts as given by Dr. Swanton, may be envisaged in this way; the processes of change are simple, natural and have parallels elsewhere.

If a totemic clan chooses to wear the image of its totem as a badge, and has no other badge, all is plain sailing. But in British Columbia, as in Central British New Guinea, men, in proportion to their wealth and descent, wear an indefinite number of badges or "crests." "Although referred to by most writers as totems," says Mr. Swanton, speaking of the Haida tribe, "these crests have no proper totemic significance, their use being similar to that of the quarterings in heraldry, to mark the social position of the wearers."27 Of course Australian totemists have no social position to be indicated by crests or badges. Now Dr. Boas speaks of "crests" as "totems," among the Haida,28 and we are perplexed among these mixtures of heraldic with totemic terms.

Next, and this is curious, while Mr. Swanton gives local names to the "clans" of the Tlingit; to many but not all of his "House Groups" he gives animal names, "Raven, Moose, Grizzly Bear, Killer Whale, Eagle, Frog houses" and so on. All these animals are names of Holmberg's and Mr. F. Boas' totems of clans; but, according to Mr. Swanton, they are names borne, not by "clans" but by "house groups."29 Other house groups have local names, or descriptive names, or nicknames, as "gambling house." Thus Mr. Frazer gives animal names to the "clans" of the Tlingit to which Mr. Swanton gives local names, and while many of the houses, or "house groups" of Mr. Swanton's Tlingit bear totemic names, Mr. Frazer says "the families generally take their names from places."30 There appears to be confusion due to imperfect terminology.

Mr. Goldenweizer avers that "the intensive and prolonged researches conducted by a number of well trained observers among these tribes of the North Pacific border have shown with great clearness," – something not at present to the point31 But we regret the absence of clearness. Can we rely on Holmberg who described the state of affairs as it was fifty years ago, and who knew nothing, I presume, of Australian phratries and totem kins? In his time the Tlingit, like a dozen South-Eastern tribes of Australia, had animal-named kins in animal-named exogamous intermarrying phratries with female descent. Or was Holmberg (and was Mr. F. Boas in his list of animal-named Tlingit clans) led astray by the "crests"? Did each of these inquirers mistake "crests" for totems of clans?

One thing is clear, the Tlingit and the other tribes being possessed of wealth, and of gentry, and of heraldry, cause almost inextricable confusion by their use of heraldic badges, named "crests" by some; and "totems" (or both crests and totems at once) by other well trained observers. I am inclined to believe that most of these crests were, originally, representations of the totems of distinct totem kins. My reason is this: Mr. Swanton tells us that "the crests and names which among the Tlingit are on the Wolf side" are "on the Raven side" among the Haida. Among these people, animal names and crests are divided between the two phratries, the same name or crest not occurring in both phratries. This is merely the universal arrangement of totems in phratries.

Even now, among the Tlingit, says Mr. Swanton, "theoretically the emblems" (crests) "used on the Raven side were different from those on the Wolf or Eagle side," (precisely as, in Australia, the totems in Eagle Hawk phratry are different from those in Crow phratry), "and although a man of high caste might borrow an emblem from his brother-in-law temporarily, he was not permitted to retain it" (His brother-in-law, of course, was of the phratry not his own.) All this means no more than that occasionally a man of high caste may now impale the arms of his wife.32 With castes and heraldry, born of wealth and rank, we have stepped out of totemism at this point It has been modified by social conditions. "Some families were too poor to have an emblem," did they also cease to have a totem? Some of the rich "could," it was said, "use anything." Is this because they pile up sixteen quarterings? "The same crest may be, and is, used by different clans, and any one clan may have several crests…"33 Many "clans" now use the same crest, and there are quarrels about rights to this or that "crest." Some members of the Wolf phratry assert a right to the Eagle crest. Mr. Frazer thinks that "such claims are perhaps to be explained by marriages of the members of the clan with members of other clans who had these animals for their crests."34

That is precisely my own opinion. If "crests" were originally mere representations of each person's totem animal they have now become involved, through rank and social degrees, with heraldry, and with badges not totemic, such as a certain mountain. Meanwhile all the Tlingit "clans," if we follow Mr. Swanton's evidence, or almost all the "clans" are now mere local settlements, at least they bear local and other descriptive names. I nearly despair of arriving at Mr. Swanton's theory of what a Tlingit "clan" really is! But he gives a list of "the geographical groups," the "clans," and the phratry to which each of the clans belonged…

Thus we have (1)

PHRATRY RAVEN.

Then (2)

TONGAS (I take Tongas to be "a geographical group").

Then under TONGAS GānAXA'di, People of Gā'NAX.

PHRATRY WOLF.

TONGAS (Geographical group, apparently).

Te'goedî, People of the island Teq°.

GānAXÁdî and Te'goedî seem to be "clans," but then clan Te'goedî, "People of the isle Teq°," looks like "a geographical group"!

There are fourteen "geographical divisions" of this kind, and sixty-eight "clans" of this kind, with descriptive or local names. The clans "were in a way local groups," says Mr. Swanton. They were also "clans or consanguineal bands," each "usually named from some town or camp it had once occupied." They "differed from the geographical groups … being social divisions instead of comprising the accidental occupants of one locality."35

Be it observed that Mr. Swanton speaks of "these geographical divisions or tribes"; which increases the trouble, for, if the Tlingit be a "tribe," and the geographical divisions of the Tlingit be also "tribes," things are perplexing.

Once more, the Tlingit reckon descent in the female line. Now how can "a consanguineal band," which reckons descent in the female line, look like "a geographical group"? A totem kin, with male descent, in Australia and elsewhere, like a Highland clan, say the MacIans, necessarily becomes "a geographical group," say in Glencoe. But how, with female descent (unless the women go to the men's homes), a Tlingit "consanguineal band" can also have a local habitation is to me a difficult question. The names of the phratries descend in the female line. Do the local and descriptive names of "the clans or consanguineal bands," also descend in the female line? I cannot presume to say. Mr. Frazer throws no light on this point believing, as he does, that the "clans" within the Tlingit phratries, are the familiar totem kins, of animal names. If so, the children must inherit the maternal totem "clan" name.

Only one thing is clear to me, a Tlingit of the Wolf phratry can only marry a bride of the Raven phratry; a Tlingit of the Raven phratry can only woo a maiden of the Wolf phratry. If totem kins there be in the phratries, these totem kins are exogamous. If there be no totem kins in the phratry, are Mr. Swanton's clans of local names locally exogamous? May persons marry within the region where they are settled? I know not, but I rather incline to suppose that members of both phratries may be found in Mr. Swanton's clans of local name; indeed it must be so, and therefore a pair of lovers may perhaps wed within their "clan or consanguineal band," and within their local group, which, thus, is not exogamous. If so, the Tlingit clan is not exogamous. But all this is purely conjectural.

While, in Mr. Swanton's version, the Tsimshians, with female descent, have two exogamous "clans" with animal names, and two with other names; while in Mr. Frazer's book they have four animal-named exogamous clans, there is a third story resting on the authority of Mr. William Duncan, a missionary among the Tsimshian from 1857 onwards.36 Mr. Duncan's information Commander Mayne incorporated in his book.37

According to Commander Mayne, using Mr. Duncan's evidence, in 1862, the Tsimshians (as we have seen), carved faces of "Whale, Porpoise, Raven, Eagle, Wolf, Frog, etc.," on roof beams. He calls such effigies "crests." No person may marry another of the same "crest": the children take their mother's crest, and bear the name of the animal which it represents. None may kill the animal of his crest. All this is exogamy with totem kins, under the phratries, as the exogamous units,38 and with the totemic taboo. If Mayne and Duncan are right, either more recent writers are wrong, or Tsimshian totemism has been much modified since 1862.

V

Further south than the Tsimshian dwell the Kwakiutl, of whom the most southerly are called "the Kwakiutl proper." The northern Kwakiutl are divided, says Dr. Boas, into "septs" and "clans." What a "sept" may be I am not certain. The first tribe has "clans" called Beaver, Eagle, Wolf, Salmon, Raven, Killer Whale: the usual totemic names in this region. These totemic clans are exogamous, like those of Mayne's Tsimshians. Descent is in the female line. In the next tribe we find three exogamous animal-named clans: Eagle, Raven, Killer Whale, Beaver, Wolf, and Salmon have vanished, or have never existed. In these two tribes a child is sometimes placed in the father's, not in the mother's clan, as a Dieri father sometimes "gives" his totem to his son, in addition to the inherited maternal totem.39

When we reach the southern Kwakiutl ("the Kwakiutl proper") we are told by Dr. Boas that "patriarchate prevails." This appears to mean that descent is here reckoned not, as in the north, in the female, but in the male line. "We do not find a single clan that has, properly speaking, an animal for its totem; neither do the clans take their name from their crest, nor are there phratries."40 As the northern Kwakiutl have animal-named exogamous "clans" with female descent, Dr. Boas now thinks that the northern Kwakiutl "have to a great extent adopted the maternal descent and the division into animal totems of the northern tribes."41 We do not know, elsewhere, that totemism has ever been borrowed by one tribe from another, especially by a tribe so advanced in culture as the Kwakiutl, and we have no example of a tribe in which the men have given up their social prerogatives, and transmitted them to their nephews in the female line.

Mr. Frazer writes, "The question naturally arises, Are the Kwakiutl passing from maternal institutions to paternal institutions, from mother-kin to father-kin, or in the reverse direction?.. In one passage Dr. Boas seems to incline to the former member of this alternative, that is, to the view that the Kwakiutl are passing, or have passed, from mother-kin, or (as he calls it) matriarchate to father-kin or patriarchate, for he says that "the marriage ceremonies of the Kwakiutl seem to show that originally matriarchate prevailed also among them."42 Yet he afterwards adopted with great decision the "contrary view." On these very intricate problems I take leave to quote the statement with which Mr. Goldenweizer has been good enough to favour me.

First, as to descent among the Kwakiutl proper.

"At first, as Mr. Frazer points out (iii. p. 329 sq.). Dr. Boas believed that the Kwakiutl were passing from maternal to paternal descent. Later investigations conducted by Dr. Farrand (cf. F. Boas, The Mythology of the Bella Coola, Jesup North Pacific Expedition, vol. i. p. 121), led to a reversal of that opinion. The main arguments for original paternal descent among the Kwakiutl are three in number. (1) The village communities, which were the original social unit of the Kwakiutl,43 regarded themselves as direct descendants of a mythical ancestor, and not as descendants of the ancestor's sister, which is the case in the legends of the northern tribes, with maternal descent. (Cf. F. Boas, The Kwakiutl, etc., p. 335, where a genealogy is also given.) (2) A number of offices connected with the ceremonies of the secret societies, such as master of ceremonies, etc., are hereditary in the male line (F. Boas, Kwakiutl, etc., p. 431). The Secret Societies, with their dances, are a very ancient institution among the Kwakiutl, and the male inheritance of the above offices is a strong argument for the former prevalence of paternal descent among these people. (3) The form taken by the maternal inheritance of rank, privileges, etc., among the Kwakiutl points in the same direction. When a man marries he receives crests, privileges, etc., from his father-in-law through his wife, but he himself may not use them but must keep them for his son, who, when of proper age, may sing the songs, perform the dances, use the crest, etc., which he thus receives from his mother through the medium of his father. (Cf. F. Boas, Kwakiutl, etc., p. 334.) When the young man marries he must return his privileges to his father, who then gives them to his daughter when she marries. Thus, son-in-law No. 2 receives the privileges, but again may not use them, but keeps them for his son, etc. It appears, then, that the privileges exercised by the young man before marriage are always derived from his mother, but formally he receives them from his father, who acts as a sort of guardian of these privileges until the son is ready for them. Descent here is clearly maternal, but the form of paternal descent is preserved, a plausible condition for a people who; having become maternal, still stick at least in form to the traditional inheritance from the father. If this inference be rejected, the feature becomes quite unaccountable.

"In the sentence, 'The woman's father, on his part, has acquired his privileges in the same manner through his mother' (Frazer, vol. iii. p. 333. note i), the privileges the woman's father exercised as a young man before marriage are meant. The privileges he later acquired through his wife he, of course, could not use, but had to keep them for his son. The phrase, 'each individual inherits the crest of his maternal grandfather' (Frazer, iii. p. 331, note 2), must be similarly interpreted. The crest the individual uses before marriage is meant.

"In connection with the foregoing it must be remembered that another mode of acquiring privileges, crests, songs, etc., was common among the Kwakiutl, viz. by killing the owner (cf. F. Boas, Kwakiutl, etc., p. 424, and elsewhere).

"I also cite the actual words of Dr. Boas. He believes that the intricate law by which 'a purely female line of descent is secured, although only through the medium of the husband,' can only be explained 'as an adaptation of maternal laws by a tribe which was on a paternal stage. I cannot imagine that it is a transition of a maternal society to a paternal society, because there are no relics of the former' (maternal) 'stage beyond those which we find everywhere, and which do not prove that the transition has been recent at all. There is no trace left of an inheritance from the wife's brothers; the young people do not live with the wife's parents. But the most important argument is that the customs cannot have been prevalent in the village communities from which the present tribal system originated, as in these' (village communities) 'the tribe is always designated as the direct descendants of the mythical ancestor. If the village communities had been on the maternal stage, the tribes would have been designated as the descendants of the ancestor's sisters, as is always the case in the legends of the northern tribes.'"44