He

I can't find walrus in the Latin dictionary nor anything else beginning with W somehow, but it seems all right. – Ed.

Yes, the fog was playing a dark game, but Nora could see it and go one lighter (there were several on the stream we had quitted). She produced a patent electric light.19 Aided by this, we looked about us and saw the strange denizens of the Zû.

It was now that the presence of mind of Leonora saved us. Foreseeing the probability of an encounter with wild beasts, she had filled her practicable pocket (she belonged to the Rational Dress Association) with buns and ginger-bread nuts.

The elephant now walked round, the wolves also circulated, the bear climbed his pole, the great gorilla beat his breast and roared.

Leonora was their match.

For the elephant she had a rusk, a bun for the bear, and the gorilla was pacified by an offering of nuts from his native Brazil.

THIS WAY TO THE CROCODILE HOUSEwe now read, on an inscription in black letters, and, following the path indicated, we reached the dank tank where the monsters dwell. We had arrived at a place which I find it difficult to describe. The floor was smooth and hard.

'What do you make of this?' asked Leonora, tapping her dainty foot on the floor.

'Flags,' I replied phlagmatically, and she was silent.

In the centre of the space was a dark pool, circled by crystalline palaces inhabited by the sacred snakes, from huge pythons to the terrapin proud of his tureen. Again, there was a whipsnake, and a toad, bloated as the aristocracy of old time, and puffed up as the plutocracy of to-day. For such is the lot of toads!

Now a strange thing happened.

'Hark!' said Ustâni; 'hark! hark! hark! a den is opening!'

He was right; it was the den of a catawampuss, an animal whose habits are so well known that I need not delay to describe them.

In the centre of the dark pool in the middle of the vague space lay one crocodile. The rest were sleeping on the banks. The catawampuss secretly emerged from its den – horror, I am not ashamed to say, prevented me from interfering – stealthily crept across the cold floor, and, true to the instincts of all the feline tribe,20 made straight for the water.

'Ah!' cried Ustâni, 'he's going for him!'

The expression was ambiguous, but we understood it.

The catawampuss, cunning as the dread jerboa, crept to the edge of the pool, took a header into it, and then, still true to the feline instincts, swimming on its back, made its way to the crocodile. In this manner it caught the crocodile by the tail and waked it. When the tail of a crocodile awakes the head awakes also. The crocodile's head, then, waking as the catawampuss seized its tail, caught the tail of the catawampuss. The interview was hurried and tumultuous.

The crocodile had one of his ears chawed off (first blood for the catawampuss), but this was a mere temporary advantage. When next we saw clearly through the tempest of flying fur and scales, the head of the catawampuss had entirely disappeared, and the animal was clearly much distressed.

Then, all of a sudden, the end came.

They had swallowed each other!

Not a vestige of either was left!

This duel was a wonderful and shocking sight, and was therefore withdrawn, by request, as the patrons of the Gardens are directly interested in the morality of the establishment.

CHAPTER VII.

AMONG THE LO-GROLLAS

How to escape from our perilous position on the banks of a pestilential stream, haunted by catawampodes and other fell birds of prey, now became a subject for consideration. Our object, of course, was to reach the people of the Lo-grollas, through whose region, according to the prophecy, we must pass before finding the Magician that should guide us to the mummy. Our perplexity was only increased by the discovery that we were surrounded on every side by the walls and houses of a gigantic city. Stealing out by the canal as we had entered, we found to our comfort that this must be the very city mentioned by Theodolitê. As the seeress had declared, a deep and noisome night always prevailed, only broken here and there as a wanderer scratched one of Bryant & May's matches and painfully endeavoured to decipher the number on the door of his house. The streets, moreover, were strewn and interwoven with long strings of iron fallen from the sky.

'The people who wire themselves with wires,' whispered Leonora; 'what do you think of my interpretation now?'

'I shall inquire,' I answered, and I did inquire for the land of the Lo-grollas, but in vain.

Happily we chanced to meet an old man, clothed in a whitish robe of some unknown substance, not unlike paper. This fluttering vesture was marked with strange characters, in black and red, which Leonora was able to interpret. She read them thus. They were but fragmentary.

On the fragments the words, 'Tragedy,' 'Awful Revelations,' 'Purity,' and other apparently inconsistent hieroglyphics might be deciphered.

He had a large and ragged staff; on his back he carried a vast Budget, and he was always asking everybody, 'Won't you put something in the Budget?'

'Father,' said Leonora, in a respectful tone, 'canst thou tell us the way to the land of the people called Lo-grolla, and the place of the Rolling of Logs.'

He stroked his beautiful white beard, and smiled faintly.

'Indeed, child, we not only know it, but ourselves discovered it and wrote it up – we mean, sent our representative,' he answered.

It was a peculiarity of this man that he always spoke, like royalty, in the first person plural.

'And if a daughter may ask,' said Leonora, 'what is the name of my father?'

Stedfastly regarding her, he answered, 'Our name is Pellmelli.'

'And whither go we, my father?'

'That you shall see – as soon, that is, as the fog lifts, or as our representative has made interest with a gas company.'

With these words he furnished an unequalled supply of litter, which came, he said, 'from the office,' where there was plenty, and we were borne rapidly in a westward direction.

As we journeyed, old Pellmelli gave us a good deal of information about the Lo-grollas, whom he did not seem to like.

They were, he said, a savage and treacherous tribe, inhabiting for the most part the ruined abodes of some kingly race of old.

The names of their chief dwellings, he told us, were still called, in some ancient and long-lost speech,

'The Academy,' and 'The Athenæum.'

Leonora, whose knowledge of languages was extensive and peculiar, told Pellmelli that these names were derived from the old Greek.

'Ah,' said he, 'you have clearly drunk of the wisdom of the past, and thy hands have held the water of the world's knowledge. Know you Latin also?'

'Yes, O Pellmelli,' replied Leonora, and Pellmelli said he preferred modern tongues, though it would often be useful to him if he did in his dealings with the Lo-grollas.

'However, if our Greek is a little to seek, our Russian is O.K.,' he said proudly.

He was very bitter against the Lo-grollas.

The Lo-grollas' favourite weapon, he told us, was the club, and he even proposed to show us this instrument.

Our litter presently stopped outside a stately palace.

The street was dark, as always in this strange city, but old Pellmelli paused, sniffed, and, bending his ear to the ground, listened intently.

'I smell the incense,' he said, 'and hear the melodious Rolling of the Logs. But they shall know their master!'

Thus speaking, he led us into a vast hall, where the Lo-grollas were sitting or standing, 'offering each other incense,' as Pellmelli remarked, from thin tubes of paper, which smoked at one end.

'Now listen,' said Pellmelli, and he cried aloud the name of a poet known to the Lo-grollas.

Instantly we heard, from I know not what recess, a rolling fire of applause and admiration, which swept past us with stately and solemn music, like a hymn of praise.

'There,' said Pellmelli, 'I told you so. This is the place of the Rolling of Logs, and yourselves have heard it.'

Leonora said she did not mind how often she heard it, as she quite agreed with the sentiments.

'Not so!' said Pellmelli; and he cried aloud another name – the name of a poetaster – which was almost strange to us.

Then followed through that vasty hall a sharp and rattling crash, as of the descent of innumerable slates.

'Great heavens!' whispered Leonora, 'remember the writing; the place where they slate strangers!'

As we were strangers, and wholly unknown to the Lo-grollas, we thought they might slate us, and, beating a hasty retreat, soon found ourselves with Pellmelli in the dark outer air.

'They are a desperate lot,' said he; 'they won't ever put anything in the Budget.'

He was quivering with indignation; and Leonora, to soothe him, told him the story of our quest for the mummy, and asked him if he could help us.

'We are your man,' said he. 'We propose to-morrow to send our representative to interview a magician who has just arrived in this country. He is a mysterious character; his name is Asher,21 and it is said that he is the Wandering Jew, or, at all events, has lived for many centuries. He, if any one, can direct you in your search.'

He then appointed a place where his representative should meet us next day, and we separated, Pellmelli taking his staff, and going off to lead an excursion against the Ama-Tory, a brutal and licentious tribe.

CHAPTER VIII.

HE

Next day Leonora was suffering from a slight feverish cold, and I don't wonder at it considering what we suffered in the Zû. I therefore went alone to the rendezvous where I was to meet 'our representative.'

To my surprise, nobody was there but old Pellmelli himself.

'Why, you said you would send your representative!' I exclaimed.

'We are our usual representative,' he answered rather sulkily. 'Come on, for we have to call on Messrs. Apples, the famous advertisers.'

'Why?' said I.

'Can you ask?' he replied. 'Can aught be more interesting than an advertiser?'

'I call it log rolling,' I answered; but he was silent.

He went at a great pace, and presently, in a somewhat sordid street, pointed his finger silently to an object over a door.

It was the carven head of an Ethiopian!

This new confirmation of the prophecy gave me quite a turn, especially when I read the characters inscribed beneath —

Try our Fine Negro's Head!'Here dwells the sorcerer, even Asher,' said Pellmelli, and began to crawl upstairs on his hands and knees.

'Why do you do that?' I asked, determined, if I must follow Pellmelli, at all events not to follow his example.

'It is the manner of the tribe of Interviewers, my daughter. Ours is a blessed task, yet must we feign humility, or the savage people kick us and drive us forth with our garments rent.'

He now humbly tapped at a door, and a strange voice cried,

'Entrez!'

Pellmelli (whose Russian is his strong point) paused in doubt, but I explained that the word was French for 'come in.'

He crawled in on his stomach, while I followed him erect, and we found ourselves before a strange kind of tent. It had four posts, and a broidered veil was drawn all round it.

Within the veil the sorcerer was concealed, and he asked in a gruff tone,

'Wadyerwant?'

Pellmelli explained that he had come to receive a brief personal statement for the Budget.

The Voice replied, without hesitation, 'The Centuries and the Æons pass, and I too make the pass. Je saute la coupe,' he added, in a foreign tongue. 'While thy race wore naught but a little blue paint, I dwelt among the forgotten peoples. The Red Sea knows me, and the Nile has turned scarlet at my words. I am Khoot Hoomi, I am also the Chela of the Mountain!'

'Now it is my turn to ask you a few easy questions.

'Who sitteth on the throne of Hokey, Pokey, Winky Wum, the Monarch of the Anthropophagi?

'Have the Jews yet come to their land, or have the owners of the land gone to the Jews?

'Doth Darius the Mede yet rule, or hath his kingdom passed to the Bassarids?'

As Pellmelli was utterly floored by these inquiries (which indicated that the sorcerer had been for a considerable time out of the range of the daily papers), I answered them as well as I could.

When his very natural curiosity had been satisfied by a course of Mangnall's Questions, I ventured to broach my own business.

He said he did not deal in mummies himself, though he had a stuffed crocodile very much at my service; but would I call to-morrow, and bring Leonora? He added that he had known of our coming by virtue of his secret art of divination. 'And thyself,' he added, 'shalt gaze without extra charge in the Fountain of Knowledge.'

Thrusting a withered yellow hand out of the mystic tent, he pointed to a table where stood a small circular dish or cup of white earthenware, containing some brown milky liquid.

'Gaze therein!' said the sorcerer.

I gazed —There was a Stranger in the tea!

Deeply impressed with the belief (laugh at it if you will) that I was in the presence of a being of more than mortal endowments, I was withdrawing, when my glance fell on his weird familiars, – two tailless cats. This prodigy made me shudder, and I said, in tones of the deepest awe and sympathy, 'Poor puss!'

'Yes,' came the strange voice from within the tent, 'they are born without tails. I bred them so; it hath taken many centuries and much trouble, but at last I have triumphed. Once, too, I reared a breed of dogs with two tails, but after a while they became a proverb for pride; Nature loathed them, and they perished. Χαιρε! Vale!'22

This, though not understood, of course, by Pellmelli, was as good as an invitation to withdraw, so I induced the old man to come away, promising the magician I would return on the morrow.

Who was this awful man, to whom centuries were as moments, whose very correspondence, as I had noticed, came through the Dead Letter Office, and who spoke in the tongues of the dead past?

CHAPTER IX.

THE POWER OF HE

Next day Leonora, the Boshman, and I returned to the home of the mage. He stood before us, a tall thin figure enwrapped in yellowish, strange garments, of a singular and perfumed character – spicy in fact – which produced upon me a feeling which I cannot attempt to describe, and which I can only vaguely hint at by saying that the whole form conveyed to me the notion of something wrapped up.23

With a curious swaying motion which I have never seen anything like – for he seemed less to be walking than to be impelled from behind like a perambulator, or dragged from in front like a canal-boat – he advanced to the table, where lay some pieces of a white substance like papyrus, all of the same size and oblong shape, which showed on their surfaces, some of them antique-looking figures and faces curiously stained, and others red and black dots, arranged, as it seemed to me, in some sort of design, although at first sight they looked jumbled enough. Near to these lay a book bound in brown, but with heavy black and gold lettering, amid which I thought I could make out the words Modern Magic, and the name Hoffmann. The swathed figure poised itself a moment, resting one thin hand on the table, and then spoke.

'There is naught that is wonderful about this matter,' it said, 'could you but understand it. Prestigiation itself is wonderful, but that its phases and phrases should be changed is not wonderful. Not now, I ween, is the gibecière of the Ancient Wizard seen; not now the "Presto, pass!" of the less ancient conjurer heard. Nay, all things change, yet I change not; that which is not yet cannot yet have taken place – at least not its proper place; that which shall not be may yet come to a bad pass, and the blind race of man watches helpless the trammels it could shake off did it but greatly dare. My business, ladies and gentlemen, now is, as I have just explained to you, to attempt to puzzle your eyes by the quickness of my fingers. Yours, on the other hand, will be to detect the way – or modus operandi, as old Simon Magus used to say – in which I perform my little wonders – if you can. Will any gentleman lend me a helmet – I mean a hat?'

As the only male person present was the Boshman, this appeared to me a futile question, and even the stately Magician seemed to be struck by some dim idea of the kind, for I could discern a pair of mysterious eyes peering anxiously through his swathings, and I heard him mutter to himself in several languages, 'Ought to have thought of that. No hat present. Don't know any trick to produce one. Nothing about it in the book.'

But he recovered himself quickly, and went on in clear cheerful tones, 'Ladies and gentlemen, as no person present has a hat, I will proceed to another of the tricks on my little programme. Will any lady oblige me by drawing a card? Will you, madam?' he said, bowing with infinite grace to Leonora.

Her hand touched Asher's as she drew a card, and I saw a shiver pass over the veiled figure.

'Will the lady on your left now oblige me?' he continued, turning to me, who was indeed standing on Leonora's left hand, though how he knew it is a thing I have never been able fully to understand.

'Now, please,' he continued, 'look well at your cards, but do not show them to me or to each other. Basta. Assez. Κογξ Ομπαξ. Now, please, still hiding the cards from me and from each other, exchange them. Now,' he continued, his form dilating with conscious power, 'see how true is it that change is perennial, even so far as magic and Nature herself can be perennial. For she who held the King of Hearts now holds the Queen of Spades, and she who held the Queen of Spades now holds the King of Hearts. Thus much among the shifting shadows of life can I, the wizard, see as a sure and accomplished fact. Is it not so, my children?'

We bowed in silence, overawed by the wonder of his presence, although Leonora whispered to me, 'He has got the cards wrong, but we had better say nothing about it.'

'And now,' he continued, 'look upon this glass (it was an ordinary wineglass) and on this silver coin,' producing a stater of the Eretrian Republic. 'See! I place the coin in the glass, and now can I tell you by its means what you will of the future. There is no magic in it, only a little knowledge of the secrets, mutable yet immutable, of Nature. And this is an old secret. I did not find it. It was known of yore in Atlantis and in Chichimec, in Ur and in Lycosura. Even now the rude Boshmen keep up the tradition among their medicine-men. Vill any lady ask the coin a qvestion?' he continued, in a hoarse Semitic whisper, for all currencies and all languages were alike to him. 'Sure it's the coin 'll be afther tellun' ye what ye like. Voulez-vous demander, Mademoiselle? Wollen Sie, gnädige Signora?'

'Then,' said Leonora, in trembling accents, 'I demand to know if I shall find that which I seek.'

The figure, drawing itself up to its full height, passed its hand with a proud, impatient, and mystic gesture across the glass, and then stood in the attitude of one who awaited a response. 'Should the coin, my daughter, jump three times,' he said, 'the answer is yea. Should it jump but once, nay.'

We waited anxiously. The coin did not jump at all! The wizard took up the glass, shook it impatiently, and put it down again. Still the coin showed no sign of animation. Then the wizard uttered some private ejaculations in Hittite, but still the coin did not move. Then he affected an air of jauntiness, and said, 'I remember a circumstance of a similar kind when I was playing odd man out (τριος ανθρωπος dear old Sokrates used to call it) with Darius the night before Marathon. Darius was the Mede. I was the Medium.' Then he seemed about to work another wonder, when he was interrupted by the harsh cackling laughter of the Boshman, who advanced with careless defiance and observed in his own tongue, which we all knew perfectly, that he 'could see all the tricks the wizard could do and go several better.' I waited, horror-struck, to see what would follow this insolence.

Asher made a movement so swift that I could scarcely follow it; but it seemed to me that he lightly laid his hand upon the poor Boshman's head. I looked at Ustâni, and then staggered back in wonder, for there upon his snowy hair, right across the wool-white tresses, were five finger-marks black as coal.

'Now go and stand in the corner,' said the magician, in a cold inhuman voice. The unhappy Boshman tremblingly did his bidding, putting his hands to his head in a dazed way as he went, and, incredible as it may seem, thus transferring – as if the curse carried double force – some of the black mark to his own fingers.

'I will now,' continued the wizard, who had regained his ordinary polished, if somewhat swaying and overbalanced, manner – 'I will now, with your kind permission, show you a little trick which was a great favourite with the late Tubal Cain when we were boys together. Observe, I take this paper-knife – it is an ordinary paper-knife – look at it for yourselves. I will place it on my down-turned hand. It is an ordinary hand – look at it for yourselves, but don't touch it; the consequences might be disastrous.'

I, for my part, having seen the consequences in the case of Ustâni's hair, had no desire to do so.

'You see,' continued the sorcerer, 'I place the paper-knife there! It falls. Why? Because of gravity. What is gravity? Newton, as you know well, invented the art; but what of that? Did he find that which did not exist? No, for the non-existent is as though it had never been. But now, availing myself of the resources of science, which is ever old and ever young, I clasp my wrist – the wrist of the hand on which the paper-knife rests – with the other hand, and – you see.'

As the sorcerer spoke, he deftly turned his hand palm downwards, and the paper-knife fell with a crash and a clatter on the floor. It was terrible to see the dumb wrath of the swathed figure at this new defeat.

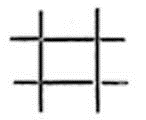

Even in this moment the Boshman glided like a serpent among us, picked up the paper-knife, and triumphantly performed the very miracle in which the wizard had failed. A harsh cackle of laughter announced his success. But the mage was even with him, or rather he was 'odds and evens.' Rapidly he drew his forefinger across the Boshman's face, perpendicularly and horizontally —

On the skin of Ustâni, azure with terror, appeared the above diagram in lines of white! The mage then made the sign of a +, thus —

and challenged Leonora to a contest of skill in 'oughts and crosses.' But the Boshman, catching a view of his own altered aspect in a mirror, exclaimed, 'You 'standy Ustâni? Him no standy He! Him show hisself for tin! Adults one shilling, kids tizzy. Me Umslopoguey!' And he sloped; nor did we ever again see this victim of an overwhelming Power (limited).

We presently took our leave of the mage, promising to call next day, and bring a policeman.

CHAPTER X.

A BODY IN PAWN

'Gin a body meet a body!' – BurnsThough Leonora's faith in the magician had been a good deal shaken by his failures in his black art, she admitted that, as a clairvoyant, he might be more inspired. We therefore went, as he had directed us, to the neighbourhood of Clare Market, where he had prophesied that we should find a Temple adorned with the Three Balls of Gold, which the Lombards bore with them from their far Aryan home in Frangipani. Nor did this part of the prophecy fail to coincide with the document on the mummy case. Through the thick and choking darkness which has made 'The Lights of London' a proverb, we beheld the glittering of three aureate orbs. And now, how to win our way, without pass-word or, indeed, pass-book, into this home of mystery?

Here, in these immemorial recesses, the natives had long been wont to bury, as we learned, their oldest objects of interest and value. There, when we pushed our way within the swinging portal, lay around us, in vast and solemn pyramids of portable property, the silent and touching monuments of human existence. The busy life of a nation lay sleeping here! Here, for example, stood that ancestral instrument for the reckoning of winged Time, which in the native language is styled a 'Grandfather's Clock.' Hard by lay the pipe, fashioned of the 'foam of perilous seas in fairy lands forlorn,' the pipe on which, perchance, some swain had discoursed sweet music near the shady heights of High Holborn. The cradle of infancy, the gamp of decrepitude, the tricycle of fleeting youth, the paraffin lamp which had lighted bridal gaiety, the flask which had held the foaming malt, – all were gathered here, and the dust lay deep on all of them!