An Introduction to Management Studies

1.5.1 System View of Organizations

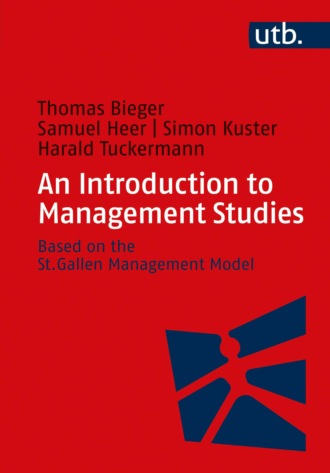

[36] Ulrich (1968, p. 105) defined systems as an “ordered totality of elements between which relationships of some sort exist or can be established.” These elements can be represented by graphs in which arrows show the relationships between elements (Figure 1-8).

Figure 1-8: Tourism as an Illustrative Example of an Open System

Source: Bieger (2010, p. 64); based on Kaspar (1996, p. 12)

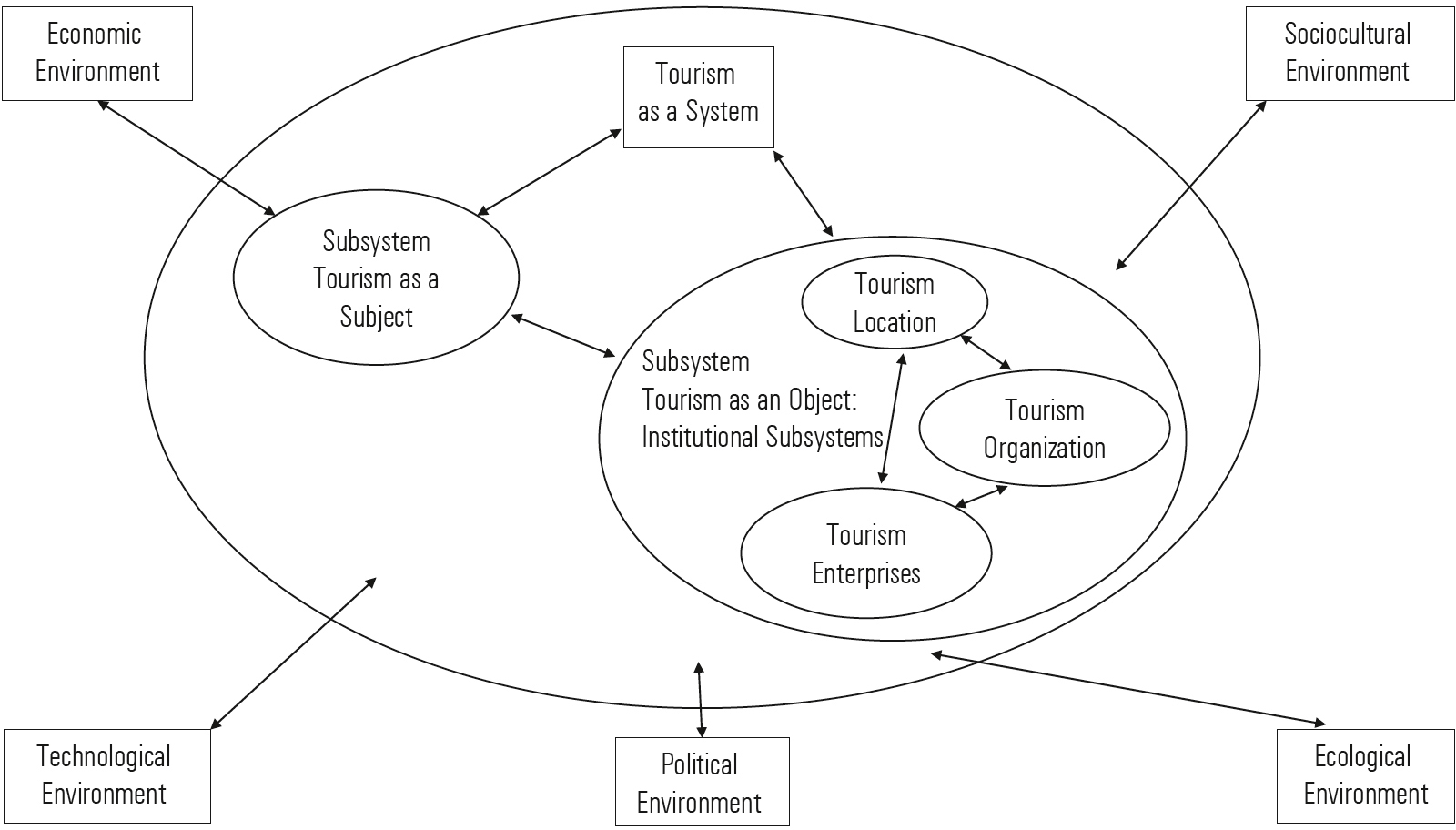

Different types, each describing the structure of systems and often represented as networks, are evident (see also Bieger, Pechlaner, Liebrich, & Beritelli, 2004). Thus, star networks, on the one hand, and mesh networks, on the other, are extreme cases (Figure 1-9). Pure star networks are centered on one element that “controls” the network, so to speak. Network development, however, also depends on the capacities of this central element. Consider logistics networks: For example, the hub-and-spoke networks of airlines handle traffic via a central hub (i.e., an airport offering transfer connections). Other examples include management consulting teams or the classical structures of academic chairs at universities, where all communication and working relationships are steered and thus also monitored by the managing partner or the chairholder (full professor).

[37] In mesh networks, relationships exist between different elements. In extreme cases, every element is connected with all others. The advantage of such systems is their redundancy. If one element fails, its functions can be performed by other elements. This basic idea also underpinned the development of the World Wide Web. In previous IT structures, remote terminals were connected to a central computer. If this failed (e.g., due to a terrorist attack or a technical fault), the entire IT system was paralyzed. Initiated by the military, the development of the World Wide Web sought to create an IT system that would continue functioning even in adverse cases because all computers were interconnected (see Deitel, 2012). On the downside, these systems are difficult to control because the central node through which everything could be controlled is missing.

A special case of the mesh network is the grid network. This consists of a rectangular network whose elements are connected to their neighboring elements on all four sides. If one of the nodes in a grid network fails, it is possible to switch to parallel connections. This explains why grid networks are often used in road and traffic planning.

Figure 1-9: Exemplary Types of Networks to Represent Systems.

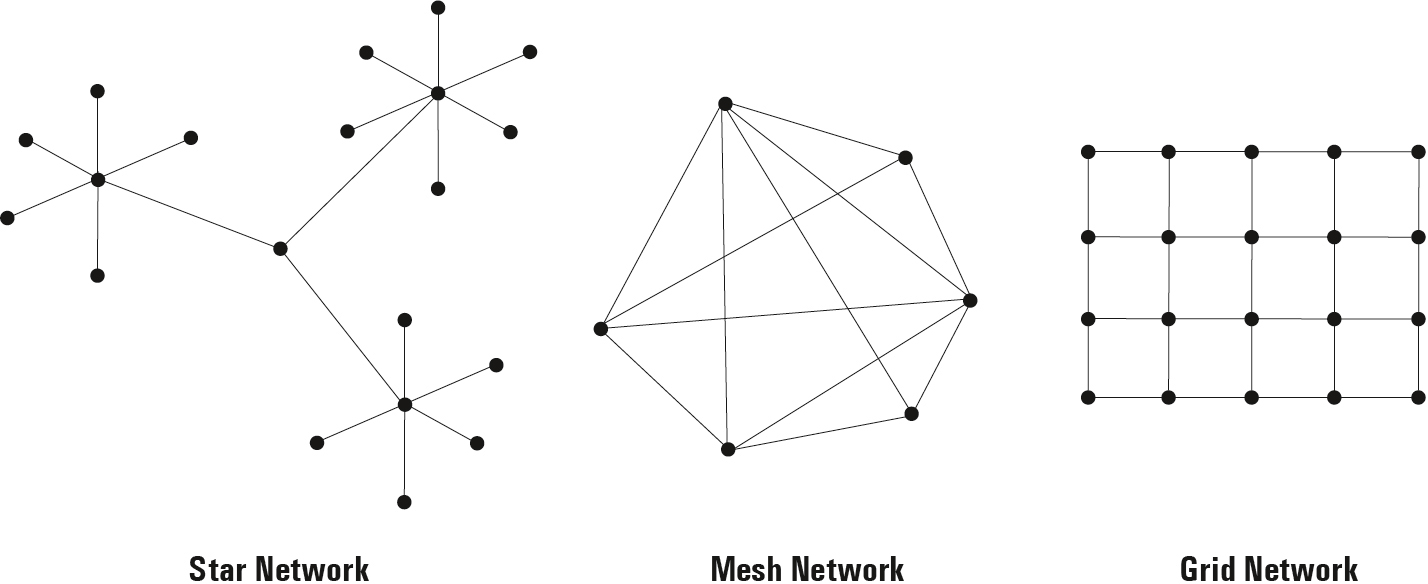

[38] Every organization consists of different system levels (see, e.g., Schräder, 2000, p. 153). For example, a socio-technical organization such as a hospital has the following levels:

– a logistical level on which patient flows occur and on which different service elements (e.g., radiology department, laboratory, operating rooms) are combined to form a specific service chain for patients;

– an information level on which patient data are collected and made available in close conjunction with the logistical level;

– a financial level on which the financial flows between the different elements take place (e.g., the billing of services from the X-ray department to the treating ward and the individual patient);

– a hierarchical level consisting of reporting relationships and cooperation structures (e.g., in projects);

– a social level comprising personal and business acquaintances and informal communication relations.

Figure 1-10: Schematic Representation of System Levels Using the Example of a Hospital

Source: Bieger (2010, p. 75)

[39] These different levels influence each other (Figure 1-10). Thus, good interpersonal relations between two department heads positively impacts the logistical level by facilitating cooperation.

Systems can also be distinguished according to whether they are trivial or complex (von Foerster, 1993). Trivial systems are characterized by their stability (i.e., the same relations always exist between the same elements). Thus, one element has a stable effect on another: For example, if one element grows, the other element also grows. Many logistics systems are trivial systems — for instance, a firmly coupled value chain supplying glasses and involving a stable relationship between the suppliers of semi-finished products, manufacturing, and delivery to retailers. Such systems can be easily analyzed and controlled. In terms of Ashby’s Law (Ashby, 1985), their variety is low, meaning the entire system can be controlled with individual interventions (e.g., changing production capacity).

Matters are different with complex systems. These are characterized by:

– Openness. Complex systems constantly receive external impulses. As a socio-technical system, a company is affected, for example, by cultural values changing in its social environment, which in turn change employee behavior.

– Structural instability. The system restructures itself continuously, as individual elements or relationships emerge or disintegrate. For example, when communication relationships between individual organizational members stall in a hierarchical system due to conflicts, or even when leading figures are dismissed as a result of these conflicts and thus cease to be system elements.

– Tilting effects. The relationship between the elements is nonlinear, allowing tilting effects to occur. This happens, for example, when a management relationship is too strongly focused on performance and control, and intrinsic motivation suddenly vanishes as a result.

– Multilayeredness. The elements change their mode of action and behavior, especially if they are affected by changes on another impact level or by another system. If a manufacturing department [40] reduces maintenance due to cost-cutting measures (impact of the financial level), and malfunctions become more frequent as a result, this in turn impacts the system’s logistical level.

– Historicity. Complex or nontrival systems are historical. Their current state and way of operating depends — among other aspects — on their past. Basically, any event or decision can alter the current state and way of operating. Vice versa, historicity also means that prior decisions inform current and future ones. So-called path dependencies can occur. For example, an organization keeps using a certain software package, even though more potent alternatives have become available in the meantime.

Consequently, the behavior and development of complex systems are very difficult to predict. This is also evident, for example, in the case of a pandemic. Whereas virus propagation can be definitively modelled under stable (i.e., “biological,” laboratory-based) conditions, this is more complex for the living world where many system levels interact. Even at the biological level, nature is open-ended. Viruses can be carried into a country or jump between living beings. Human behavior results not only from events on the biological level, but also very much from those on the economic, political, and societal level (strength of the economy, trust in authorities, local culture of dealing with each other).

Similar interactions apply to companies if, for example, a business model that is consistent at the logistical and financial levels cannot be implemented because external influences (e.g., political conflicts) cause resistance at the social and emotional levels. Systemic analyses help to describe, model, and thus explain how companies and organizations behave in their environment.

1.5.2 Process View of Organizations

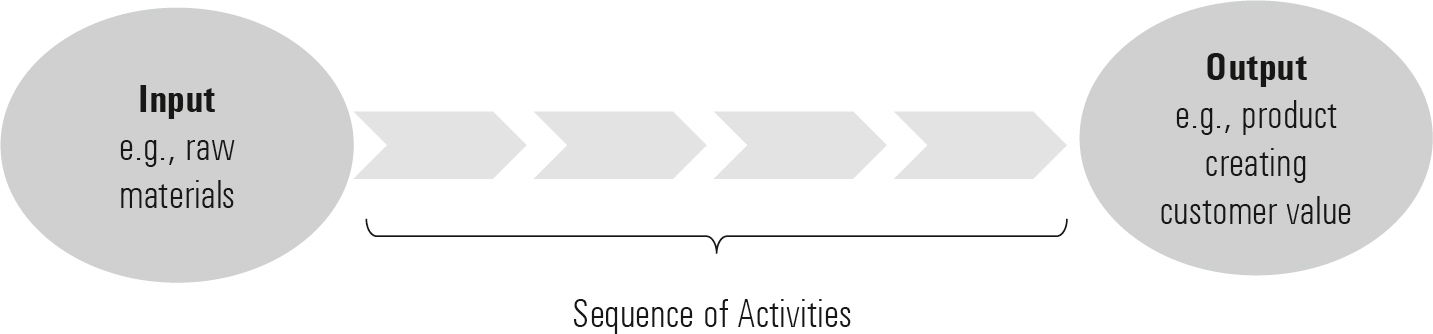

[41] Processes can be defined as a sequence of activities leading from one or more types of input to an output (see Porter, 1985) (Figure 1-4). The foundation and primary process of every organization is value creation. An organization defines itself in terms of its services. This orientation toward the customer value of a service is represented by the business processes at the heart of the St. Gallen Management Model (SGMM).

A value creation process must increase value between input and output (Figure 1-11). This value can be material (i.e., monetarily calculable) because input and output are traded on markets and thus have a price. This value creation can be distributed to stakeholders or used to further develop the company (Bieger, 2019). Value, however, can also be intangible, for example, when volunteer work enables care services or cultural creation unavailable in this quality on the market. Value is then designated, for example, via the required input (i.e., the amount of work) (for a critical exploration of value concepts, see Mazzucato, 2018).

Figure 1-11: Illustrative Process Chain

Besides the necessary steering of process activities (coordinating capacity and quality, etc.), the following aspects of value creation processes are of interest from a management perspective:

– Value chains tend to be restructured on an ongoing basis. Environmental changes (e.g., new technology or changed prices for input factors) mean that activities need to be carried out differently or that value chains may even need to be reconfigured. For example, “print on demand” makes stocking spare parts unnecessary.

– [42] Value chains tend to become increasingly differentiated and specialized as a result of the underlying “economies” (e.g. economies of scale).

– Additional value (e.g., boosting the attractiveness of a region by creating jobs and paying taxes) is created beyond primary value creation (Figure 1-12).

Figure 1-12: Differentiation of an Organization’s Primary and Additional Value Creation.

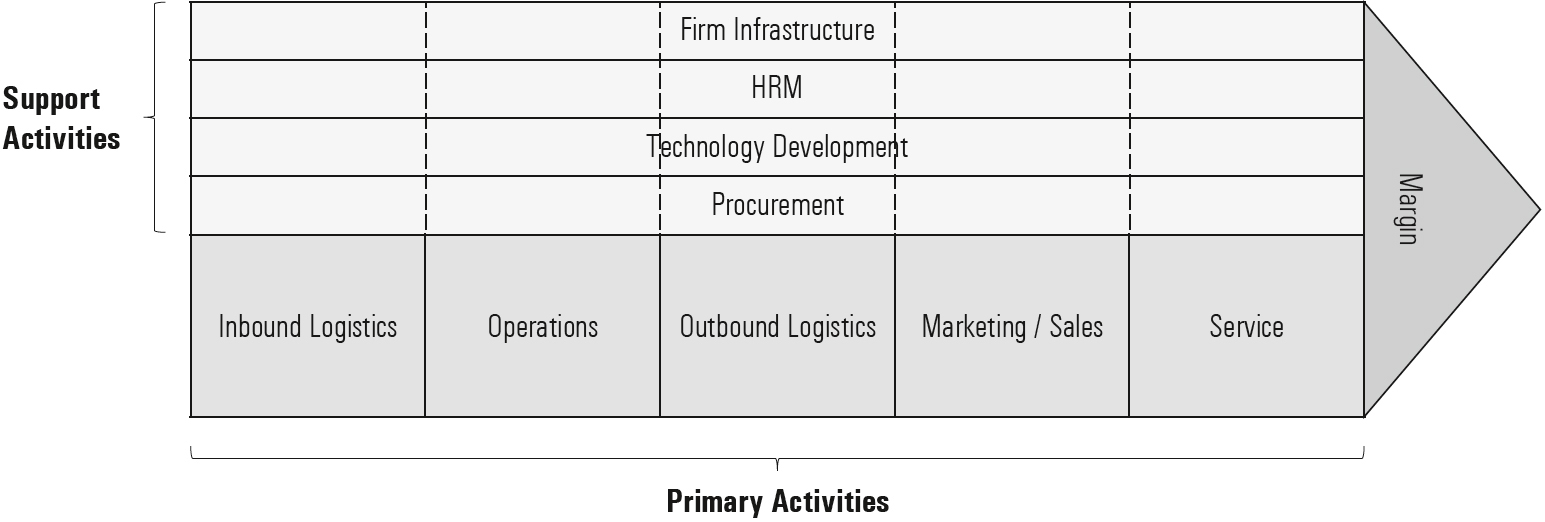

A process view of a company helps to optimize interactions between individual processes across functions. Porter’s (1985) basic process model of a company distinguishes primary and supporting activities. The former focus on the value creation process, while the latter establish the prerequisites (Figure 1-13).

Figure 1-13: The Value Chain

Source: Porter (1985, p. 37)

[43] For complex projects (e.g., purchasing a subsidiary) but also for complex service processes (e.g., recruiting a new executive, installing manufacturing machinery), process planning models are developed with the help of different techniques.

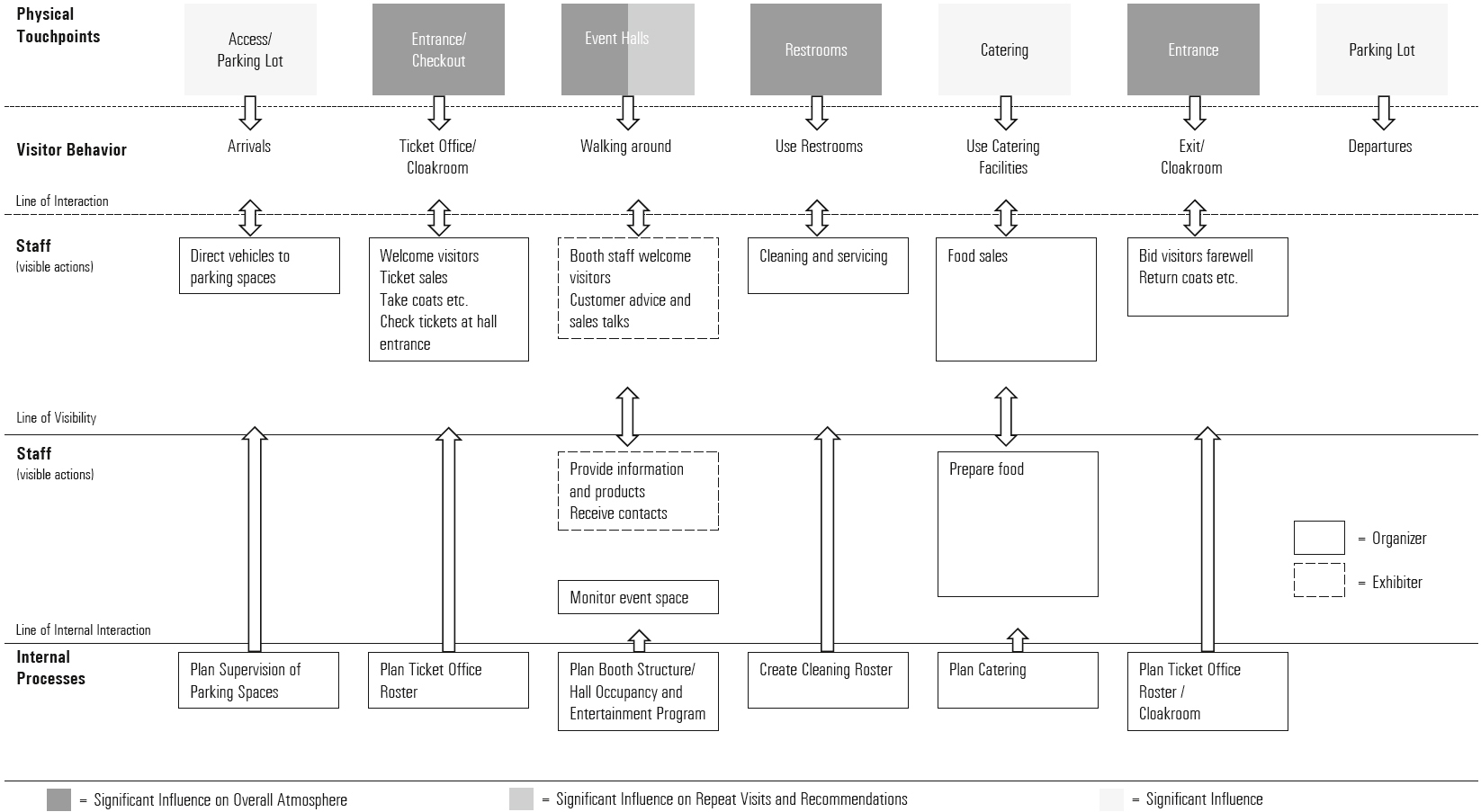

So-called “service blueprints” are often used to represent to-be processes (ideal situation). This normative design instrument is used to show various levels as well as a so-called visibility line. At the top are the customers or the physical points of contact with them (Figure 1-14).

Figure 1-14: Illustrative Service Blueprint: The Example of a Public Trade Fair

Source: Wiedmann and Kirchgeorg (2018, p. 56)

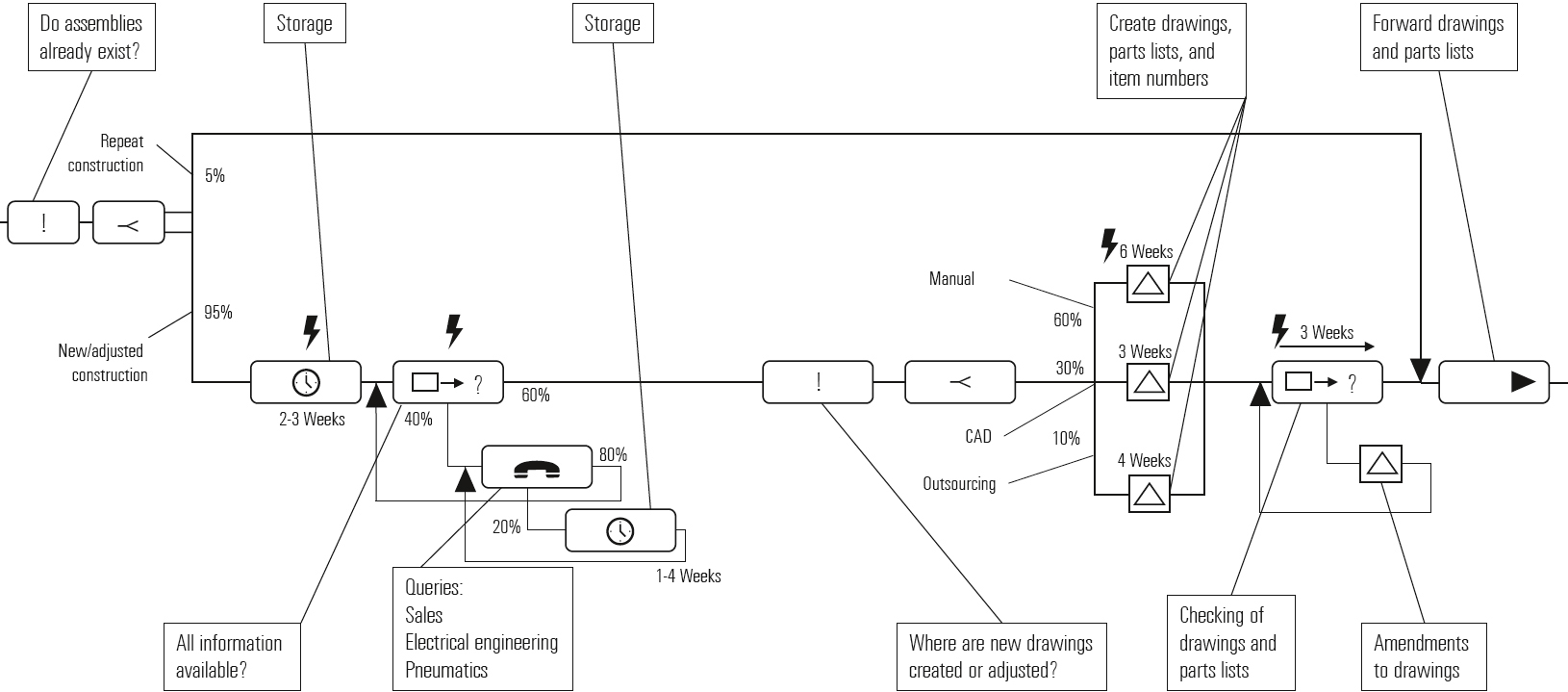

[44] Process maps, for example, can be used to show as-is (i.e., real) processes. These descriptive recording instruments enable empirically recording processes (i.e., as existing in reality) and displaying them as a process diagram (Figure 1-15). These process maps provide the basis for continuously improving such sequences of activities, because they illustrate the interdependencies of these activities.

Figure 1-15: Illustrative Example of a Process Map (ITEM-HSG Project Documentation)

Source: Rüegg-Stürm and Grand (2020, p. 83)

1.6 Types of Companies and Organizations

[45] How the management tasks described above are prioritized and performed, and how the corresponding questions are answered, depends not only on the environmental context but foremost on the type of organization. Various criteria (Figure 1-16) can be used to typify organizations (based on Rüegg-Stürm & Grand, 2020, p. 36; Thommen, Achleitner, Gilbert, Hachmeister, & Kaiser, 2017, p. 25).

Figure 1-16: Various Criteria and Their Categories Used to Typify Organizations

Source: based on Rüegg-Stürm and Grand (2020, p. 36); Thommen et al. (2017, p. 25)

[46] The type of organization and, above all, its economic (i.e. profit) orientation, significantly impacts the performing of management tasks and the force fields arising in the process. This is exemplified by the weighting of individual stakeholder interests.

Besides the differentiation according to the dominant environmental sphere, distinguishing organizations by profit orientation — “for profit” versus “not for profit” — is very important. Private companies seek profit, mostly directly or indirectly. They use their profit to compensate the risk capital needed, for example, to pursue risky innovation activities (e.g., when listed pharmaceutical companies research, test, and launch new drugs). Nonprofit enterprises mostly pursue social goals (e.g., NGOs operating in the field of development strive to combat poverty, while private foundations promote cultural projects). Not-for-profit companies are often financed by return on capital and donations, but also by their service fees (e.g., project services) or subsidies. In order to raise funds, they must document their success in attaining their goals in order to attract potential funders. For example, in 2019, the Bergwaldprojekt foundation had a total of CHF 1,726,754 in donated funds, which it invested in mountain forest conservation projects for 12,275 working days (Varinska, 2019).

Cooperations between public and private organizations are called “public-private partnerships.” Typically, such organizations often involve profit-seeking and nonprofit-seeking companies coming together. For example, the cooperative members of the Swiss Society for Hotel Credit include the hotel industry, the banking sector, the federal government (the most important member), and individual cantons. The Society grants subordinated loans to promote the hotel industry in regions with seasonal tourism. Such loans are granted in the interests of the public sector (i.e., the regions benefiting from funding), or of the hotel industry and the lenders.

Another important typification structures companies according to size. Large companies are usually more differentiated and have various management levels, whereas microenterprises (e.g., startups) are often managed directly and personally by a team. Thus, the management structure, management culture, and degree of formalization of management vary greatly — and also result in differences between the flexibility and agility of companies.

[47] The different legal forms of organizations provide different conditions for financing and growth, but also imply different requirements for management structure. While a simple partnership is usually managed by the owners, corporations are characterized by the separation of ownership and management, thus placing special demands on corporate governance. In most countries and cases, stock corporations have a two-tier system, in which a board of directors/supervisory board represents the owners/stakeholders while executive directors/management/board of directors run the company.

Figure 1-17: Typical Phases of Company Formation as an Example of a Possible Corporate Cycle

Source: Grichnik, Brettel, Koropp, and Mauer (2017, p. 239)

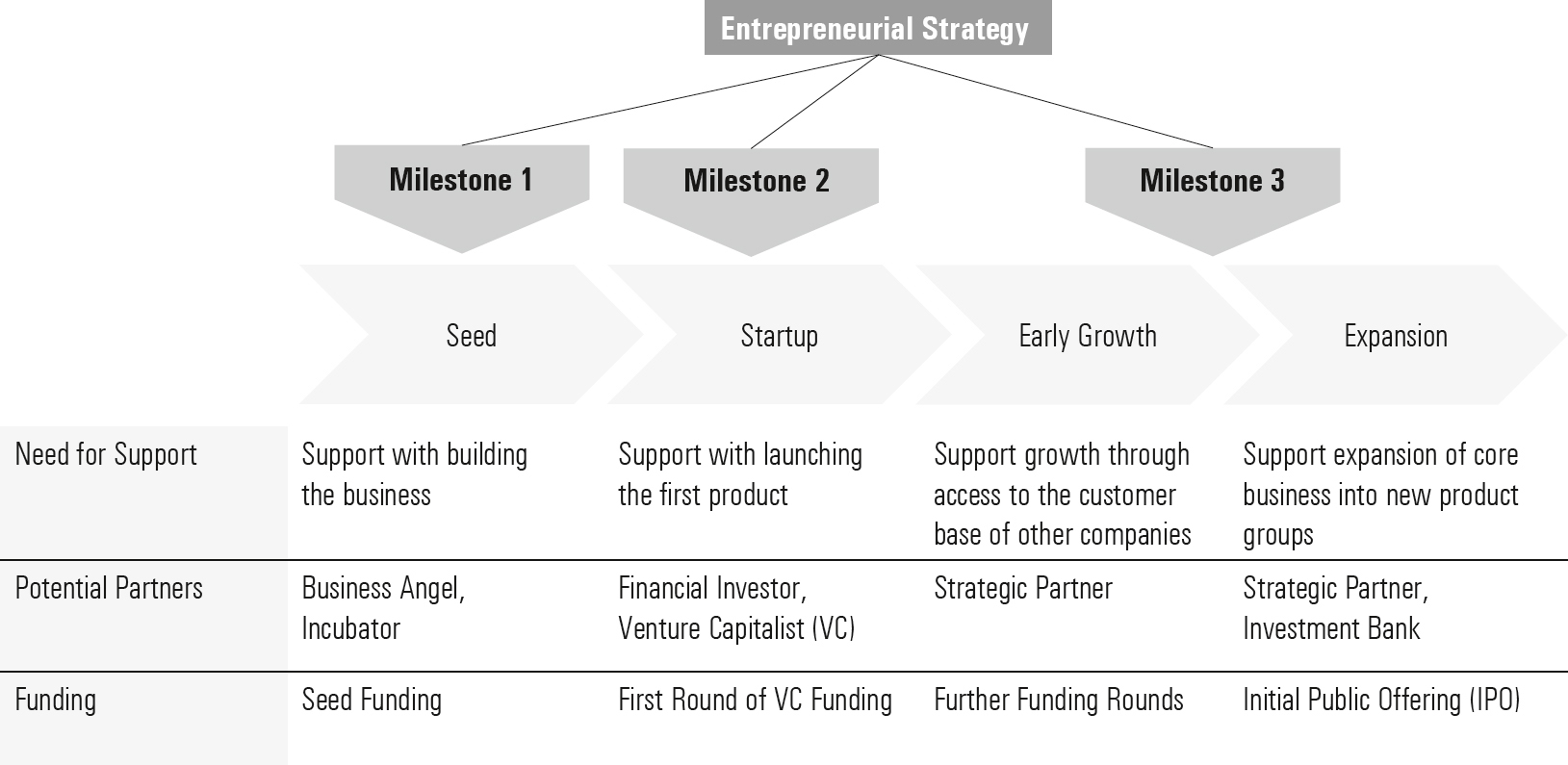

Today, the distinction by phase in the business cycle is also important. Thus, newly founded companies can be distinguished in terms of different start-up phases (Figure 1-17). While direct management (by the founding team) is possible both in a preparatory phase and immediately after a company’s founding, management will need to be transferred to more formal structures as the company grows. Whereas in the founding phase, for example, the founding team selected personnel itself, thus enabling selection to match personal values, this task is later performed by a specialized HR department.

[48] Thus, the demands on management, management structures, and managers vary depending on the type of company. However, companies change their structure not only through endogenous development processes, but also through interactions with other companies, including cooperation, consortia, strategic alliances, joint ventures, and mergers (Figure 1-18).

Figure 1-18: Forms of Corporate Ties

Source: based on Thommen et al. (2017, p. 35)

Chapter 1: Key Points

– [49] Integrative management is necessary to deal with complex management tasks.

– Classical management theory assumes that business studies should provide insights that support management and managers.

– The trend toward more scientific approaches in business studies led to a differentiation into functional subdisciplines (e.g., human resources and marketing), and to specialization according to management functions.

– Efforts to overcome the resulting “silos” brought forth various approaches, including systems-oriented management concepts.

– A systems approach helps to understand management as the reflective design of value creation systems in organizations, which in turn can be understood as socio-technical systems providing services to third parties.

– In its ongoing development, the St. Gallen Management Model (SGMM) provides a mental map, i.e., a model, for classifying and dealing with management tasks.

– Thinking in terms of systems makes it easier to grasp the developmental dynamics of organization-environment interactions.

– Thinking in terms of processes makes it easier to understand complex operations such as projects or service provision.

– Different types of organizations present different management challenges.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: