По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

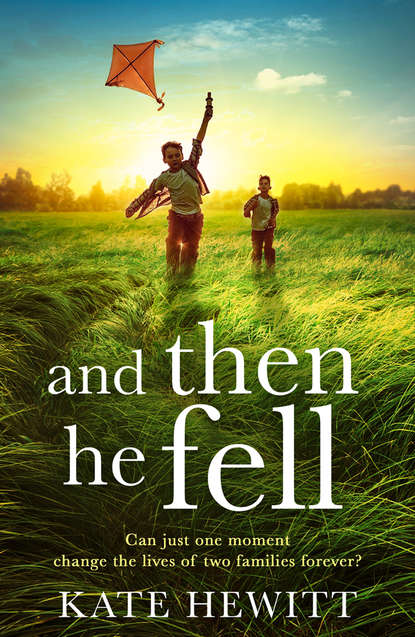

When He Fell

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But I falter when his phone switches over to voicemail, and in the end I only manage one broken word.

“Lewis,” I whisper, and then I disconnect the call and press the phone to my forehead, squeezing my eyes shut tight as I do my best to block out the world.

2 JOANNA (#ulink_2c2fb197-4930-5818-a4b0-0f095a8d2266)

The day it happens is like any other. No one talks to me when I pick Josh up at school, although no one really ever talks to me. I’ve never been too friendly with the other mothers at Burgdorf, besides a few tight-lipped smiles when I manage to attend an event. Usually Lewis does the drop off and pick up; I work from eight until six or seven most days. But today I pick Josh up myself, because I’ve had a cancellation. And no one says anything.

“Hey there,” I say to Josh as he comes out of Burgdorf’s bright blue doors. A few other mothers and nannies are gathered on the sidewalk in tight little knots; the mid-October wind is chilly, funneling down Fifty-Fourth Street and they hunch their shoulders against it. Burgdorf rents an office building in midtown; only twenty years old, the school doesn’t have the kind of money that most Manhattan private schools have, with their Brownstones and big endowments.

Josh comes to stand before me, unspeaking, but this isn’t surprising. Josh has always been on the quiet side.

I’ve battled against Josh’s silence since he said his first word at the age of two and a half. No. Spoken very softly when I put peas on his plate, and Lewis and I rejoiced as if he’d just given a speech about world peace.

He said a few more words over the next few months, and then we sent him to preschool and he didn’t say anything for a year.

The director at the preschool advised testing, and so I took him to various doctors, all of whom flirted with different diagnoses. They ruled out autism or anything ‘on the spectrum’, as has become the parlance. I was relieved as well as a tiny bit disappointed. At that point I craved a diagnosis, an answer. I wanted this to be a problem I could fix, or at least treat.

They moved on to other conditions: social anxiety disorder. Social phobia. Depressive disorder. Nothing was definitive. No one offered us anything besides more therapy, possible pills. None of it really worked.

Lewis was, although he tried to hide it, exasperated with me. “He’s just a quiet kid, Jo,” he said more than once. “Let him be. He’ll come out of it when he’s ready.”

But Josh wasn’t just a quiet kid. He wasn’t just shy; he was, as one doctor had said, selectively mute. He didn’t speak for the entire first year in preschool; not one word to anyone, not even to us at home. Kids tried with him at first, offering a toy, touching his shoulder in a game of tag. He never responded, except to shy away or duck his head. Eventually the other kids saw he was different and they stayed away. Their mothers didn’t invite him to their children’s birthday parties, even when there were whole-class invitations. Kids thought he was weird, and he was weird.

But we’ve progressed a long way from those dark days, since he’s been at Burgdorf. I’d picked the school particularly, because it catered to ‘the whole child’ and was, on the brochure, ‘a place for positivity’. Lewis rolls his eyes at that kind of language and I suppose I do too, a little, but I still feel it’s what Josh needs. Kids at Burgdorf have a lot more freedom to express themselves—or not, as Josh’s case may be. They don’t have to conform to a standard, and since Josh can’t and won’t, it’s the perfect—or at least the best—place for him. In kindergarten he started speaking again; in first grade he even made a friend. Ben Reese. The two have been best friends for nearly three years. Josh’s first and only friend, and I am as proud as if I managed the whole thing myself.

In reality I’ve only met Ben’s mother Maddie a couple of times; I’ve only seen Ben a little more than that. When they have play dates—an expression I loathe and yet accept—Lewis usually takes them out while I am at work.

Now Josh and I ride home on the subway, all the way from midtown to Ninety-Sixth Street, and he doesn’t speak the whole way. I am not bothered; in fact I am scrolling through some emails on my phone. When we pull out of the Eighty-Sixth Street station Josh rests his head briefly against my arm.

I touch his hair lightly; his eyes are closed. “Are you tired, Josh?” I ask as I delete an email from my phone. He doesn’t answer, and I decide he is.

We arrive home fifteen minutes later and Josh disappears into his room, as he often does, usually to read one of his Lego or nonfiction fact books. He’s insatiable when it comes to trivia; most of our conversations involve Josh reciting all he knows about some specialized subject. Did you know earthworms can live for up to eight years? But they die if their skin is dry. They have nine hearts.

I cannot retain the trivia, although I do try to listen to Josh and absorb it. I enjoy the evidence of his passion, even if it is simply for a collection of forgotten facts.

His other passion is Lego, although he’s never actually built anything with the blocks. He just likes studying the designs in the Lego books we’ve bought him.

While he’s in his room I make him a snack of dried fruit and nuts and pour a glass of water, the healthy alternative to cookies and milk. Lewis rolls his eyes at my insistence on things like limited screen time and no sugar or additives; he grew up on Twinkies and endless TV. But this is the plight of the modern mother; if I didn’t do these things I would be judged. Condemned. Add the fact that I am a dentist and a mother in Manhattan, and it all becomes exponentially more intense.

Lewis comes home as I am making dinner, a healthy meal of brown rice and low-fat chicken strips seasoned with paprika. I’m not very good at cooking, not like Lewis, who can throw together a bunch of ingredients with careless ease and emerge with something that tastes delicious. I follow recipes to the millimeter; it’s how I’ve always lived my life. Lewis will laugh as I level off a teaspoon, eyeing its flat surface like a nuclear physicist measuring plutonium. He never measures anything, and somehow it all works out for him.

“How was work?” he asks as he comes in the door. He shrugs off his scuffed leather jacket and rummages in the fridge for a beer. As usual when I see him I feel my insides lurch with that intense mix of love and trepidation that I’ve felt since the moment Lewis laid eyes on me at a party when I was a grad student and he worked as a maintenance man for an apartment building in Queens.

I never thought he’d be interested in someone like me. Someone who was tall and lanky with the awkwardness of a giraffe rather than the grace of a gazelle. I’d sat squeezed on a sofa at that party, a plastic cup of cheap wine clutched in my hands, and wondered why I’d come. I’ve never been good at parties; small talk has always defeated me. But I was in my first year at Columbia’s College of Dental Medicine, and I was determined to make friends.

Lewis was the kind of guy who was so inherently comfortable in his own skin that you couldn’t help but feel jealous. You wanted to be like him, or if you were a woman, you wanted to be with him. I wanted both.

When he plopped himself down on the sofa next to me, elbowing someone else out of the way, and then actually talked to me, I was incredulous. I couldn’t believe this charming man with the curly dark hair and the liquid brown eyes, the workman’s physique and the big, capable hands, was interested in me.

He asked me to dance. When we stood up I realized, to my complete mortification, that I was a good two inches taller than he was. I slouched towards the cleared space that served as a dance floor; Lewis rested his hands on my hips, unconcerned, while I contorted my body to somehow seem shorter than he was. We danced for two songs before Lewis offered to get me another drink. I accepted in the vain hope that alcohol might strip away a few of my inhibitions.

He spent the entire evening with me. I don’t remember what I said; I babbled about wanting to be a dentist and when Lewis opened his mouth to teasingly show me his gold crown I laughed in a high, whinnying way, like a horse. I was so incredibly nervous; my hands were sweaty around my plastic cup. I was afraid he’d leave me alone, and yet I almost wanted him to, was desperate for him to, because being with him was so intense, so invigorating. By eleven I was exhausted.

Lewis walked me to the subway station, and asked for my phone number before I went down the steps. I remember scrabbling in my bag for it, because I hadn’t actually memorized my own number. I remember asking for his, shyly, blushing, and he’d rattled it off with a grin. I remember almost blurting why are you interested in me before I thankfully thought better of it. And then I half-floated, half-stumbled home, caught between euphoria and terror that I might see him again.

“Where’s Josh?” Lewis asks as he pops the top on his beer and raises the bottle to his lips.

“In his room, as usual. You know how he is.” I speak lightly, as if in doing so I can dismiss the years of worry, of terror, of doctors and diagnoses, and make everything seem normal. It is normal, for Josh; I know I need to accept who he is, and who he isn’t. And I have accepted it, for the most part. It is only occasionally that I wonder if things are truly okay, or wish that they were different.

Lewis wanders over to the TV and flips it on before flopping onto the couch. I watch him sprawled there, torn between reminding him of our no screen time rule during weekdays, at least when Josh is awake, and just watching him, my heart suffused with love.

Lewis must sense my stare for he glances up from the TV, smiling slightly as he raises his eyebrows. “Come here,” he says, and I leave the chicken hissing and spitting on the stovetop and walk towards him. He holds out his arms, and I snuggle into him as best as I can; I am all awkward angles and elbows, but somehow when Lewis puts his arms around me, I soften. I fit.

He strokes my hair absently as he watches the news and I close my eyes and savor the moment until I smell the chicken starting to burn and I rise reluctantly from the sofa. I turn the chicken to simmer and start to set the table.

I call Josh, and he comes into the dining alcove, its one window overlooking the concrete courtyard behind our building. We live in a classic six on Central Park West, in a shabby building that has the benefit of a doorman and a nice address. The lobby is all peeling plasterwork and scuffed marble, and the residents tend to be people who have lived there forever or, like us, saved every last penny to buy real estate in Manhattan.

I dole out the chicken and rice while Lewis gets another beer and Josh sits at the table, his head bowed. I finally notice that something might be wrong.

“Josh?” I ask, pitching my voice light because I know I tend to panic. “You okay?”

He nods, his head still lowered, his dark, silky hair falling in front of his face. Lewis glances at him, frowning slightly, but he doesn’t press. Lewis is of the old-school belief that you let kids fall and scrape their knees so they can get up again, bloody and proud; you let them be bullied so they learn to be tough. Yet he is also the more involved parent, doing the school run and being at home in the afternoons, even if his philosophy is to be uninvolved. I, for better or for worse, am the opposite.

Lewis starts talking about a new piece he’s making, a set of built-in bookcases for some Park Avenue family. For the last ten years he’s had his own woodworking business up in Harlem.

I listen and make interested noises, ask a few relevant questions. I do all the right things, even as I glance again at Josh and start to feel worried.

“Hey, Josh.” I touch his head lightly, the tips of my fingers brushing his hair. “School okay?”

“Yeah.” He toys with his fork, pushing rice around on his plate, and then arranging the grains in a pattern. “It was fine.”

“How did your history project go?” He’d brought in a poster he’d made on the American Revolution; Lewis and I had both helped with it, all of us squealing in disgust over the little-known fact that George Washington’s false teeth were not made of wood, as many believed, but rather of human teeth he’d bought from his slaves. Josh had been particularly revolted by the thought of having other people’s teeth in your mouth, never mind the injustice of them belonging to Washington’s slaves.

“I didn’t get to present it,” Josh says. His head is still bent as he focuses on arranging the grains of rice into a perfect square. “Tomorrow, maybe.” He sucks in a breath and lets it out slowly, which has always been his signal that he is done talking.

So I force myself to let it go. To stay relaxed, because I know I worry too much and I need to trust that if something is wrong, Josh will let me know. Even if he hasn’t before.

After dinner Lewis clears the dishes and Josh retreats to his room. I frown at the closed door, debating whether to go in. I could suggest we read together, as we’ve done some evenings. It was my idea and Josh agreed reluctantly, but I think he likes the Narnia books I suggested. He doesn’t protest, anyway, when I get one out and sit by his bed to read it aloud.

But it’s still early, and I have a mountain of paperwork to get through. I’ll ask again at bedtime, I decide, and read to him then. Maybe while we’re reading he’ll talk a little more, open up about whatever is bothering him. And really, what can it be? He’s only nine, after all. Maybe Mrs. Rollins scolded him, or someone pushed him in line. The traumas of an elementary education.

I am still standing there, staring at the door, as Lewis comes up to me and places a hand on my shoulder. “Don’t worry, Jo,” he says softly, and I lean back against his chest as his arm encircles me.

“How did you know I was worrying?” I ask, and Lewis presseds his thumb to the middle of my forehead.

“You had your little worry dent going on,” he says, and I manage a laugh.

“Total giveaway,” I agree and I rest there for a moment, savoring Lewis’s embrace and letting myself believe that everything really is okay. The reassurance soaks into me, allows me to relax.