По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

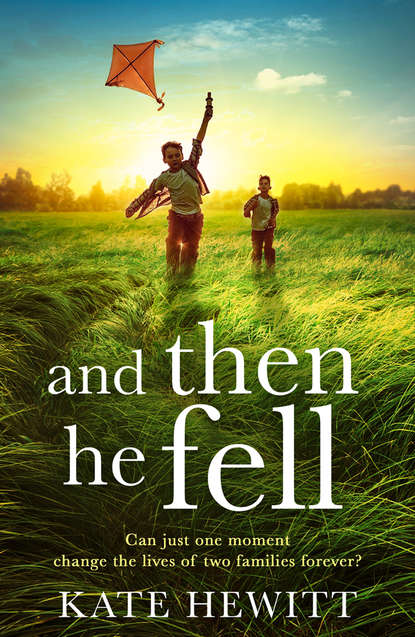

When He Fell

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Do you know Josh has been suspended?” he asks quietly, but with menace.

Mrs. Rollins blinks several times. “No, I…I wasn’t aware,” she stammers. She can’t meet any of our eyes.

“Do you think that’s fair?” Lewis demands. “Considering?”

“It’s not my place to decide on disciplinary measures, Mr. Taylor-Davies,” Mrs. Rollins says. She’s still not looking at us.

“You were there on the playground?” Lewis presses. By now children are staring; a knot of mothers has gathered by the door, their highlighted heads bent together as they whisper and dart looks toward us. They remind me of a flock of blonde crows. “You saw it happen?”

Finally Mrs. Rollins looks at Lewis. “No, I didn’t. There were two parents on playground duty yesterday.”

“Which parents?”

She hesitates, and I sense she’s nervous, even afraid. “I’m not sure…” she hedges.

“Bullshit,” Lewis snaps, and the crows outside whisper furiously. It sounds like hissing.

“You’d have to ask Tanya,” she says, and she shoots Josh a look that seems full of apology. “She has the schedule.”

Without another word Lewis marches out the doors and past the whispering mothers, his hand still on Josh’s shoulder. I follow alone. My face burns with both anger and shame.

On the corner of Fifty-Fourth and Sixth Avenue Lewis hails a cab. Thankfully one screeches to a halt in front of us within seconds; I can feel the stares of all the Burgdorf mothers boring holes into my back from halfway down the block. We all climb into the cab in silence.

Josh sits between us, his arms and legs folded up as if he’s trying to make himself smaller. I wrestle the seatbelt over his inert form as Lewis stares out the window, his jaw clenched, and the taxi inches through the midtown traffic.

I put my arm around Josh, but he remains rigid and unyielding. “We’re going to have an amazing week, doing all sorts of cool stuff,” I say firmly, and no one answers.

When we get back to our apartment, Josh disappears into his bedroom. I want to go after him, but I decide he could use a little time alone. I’ll try talking to him later. Lewis shrugs off his jacket and strides to the living room window overlooking the park, bracing one hand against its frame.

“This whole thing is bullshit,” he says. “That school is crazy.”

“They seem to have taken against Josh,” I admit quietly. The last thing I want is for our son to hear us talking like this.

“They don’t even know for sure that he pushed Ben, and if he did push him, it was obviously an accident. He and Ben were just messing around. You know how Ben is.”

Not really, actually. Ben is boisterous; I know that. When he came over one Saturday when I happened to be home—often I’m at work on a Saturday—he was zinging around our apartment like a pinball in a machine. Lewis finally took the boys out to the park. I offered to come, but they didn’t take me up on it and I was relieved. I didn’t think I could handle Ben’s energy, which was a whole other ball game from Josh’s quiet intensity.

“Why would Josh push Ben?” I ask. “He’s not a pusher.”

Lewis shrugs. “They’re nine-year-old boys. Even Josh roughhouses a little bit. When we’re all out together.”

“But then why wouldn’t Josh tell us about Ben’s fall?”

“Because he was upset, and he doesn’t talk about his feelings,” Lewis snaps. “What do you think, Jo?” He sounds accusing and I recoil at his tone. “I’m sorry,” he mutters. “I’m sorry. It’s just…” He blows out a breath, raking his hand through his hair. “This is so unfair.”

“I know it is. But I do think it’s a bit odd,” I answer. “And I want to get to the bottom of this, for Josh’s sake as much as anything else. Something doesn’t feel right.”

“What doesn’t feel right is that stupid headmistress,” Lewis retorts. “There has to be a reason why she’s coming down so hard on Josh.”

“Do you think Maddie Reese is pressuring her into it?” I don’t know Maddie at all. I’ve only met her a few times, all of them hurried occasions. My impression was of a petite, put-together woman who seemed reserved, a bit cool.

“Maddie wouldn’t do that,” Lewis says definitively, and I remember him saying I know Maddie. How well does he know Maddie? And how come? Just through Ben, through the play dates he and Josh have had, the pick ups and drop offs?

I sink slowly into the sofa. I don’t want to pursue that line of thought. Not now, not on top of everything else. “Why, then?” I ask and Lewis doesn’t answer for a long moment.

“I don’t know,” he finally says. “I feel like there’s something Mrs. James is not telling us. Something she’s hiding.”

“What could she be hiding?”

“I don’t know,” Lewis says again.

I sigh as weariness crashes over me. I’ve missed an entire afternoon of scheduled appointments. “And now Josh is off school for a week.”

Lewis shakes his head. “He’s not going back to Burgdorf.”

“What?” I stare at him. “Lewis, where else is he going to go?”

Lewis clamps his jaw. “Anywhere else.”

“You think we can get him into another private school in October?” I ask in disbelief. “You think he’ll thrive in some kind of cutthroat academic environment?”

“Public school, then.”

“We’re zoned for PS 84. You remember what we learned about that?”

“Test scores aren’t everything, Jo.”

I’m sure there are plenty of people who would say PS 84 is a very good school. It probably is a very good school, at least for Manhattan. But only a third of their students were proficient or better in both math and reading when tested in third grade. There are thirty-four kids in a class with one teacher.

That is not the place for Josh.

“Lewis,” I say and he gives a twitchy kind of shrug.

“We can figure something out. Homeschool him if we have to.”

“Homeschool? And how on earth are we going to do that when we both work? Besides, homeschooling is the last thing Josh needs. He needs to be around people, to be drawn out—”

“Do you really think he was drawn out at Burgdorf?”

“Yes. He’s been happy there, Lewis. Look at the way he’s opened up. He did a research project on Legos and he loved it. He gets fact books out of their library and memorizes them—”

“He can get fact books out of a local library, Jo.”

“Burgdorf is good for him,” I say firmly. “Do you remember what preschool was like?” We are both silent, recalling the year-long hell of Josh’s selective mutism. “This will blow over,” I say and Lewis lets out a hard laugh.

“You really think so? And what about Ben? If he really does have a serious brain injury…” He sinks into a chair, raking both his hands through his hair. “Poor Ben. I should call Maddie.”

Again I feel that shivery apprehension. “Yes,” I say, and rise from the sofa. “You should call Maddie.”