По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

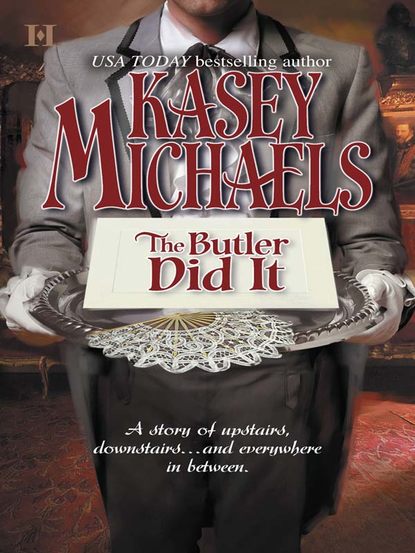

The Butler Did It

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He watched until Morgan closed the door behind him, then headed, lickety-split, for the servant stairs, where he met Thornley, who was ascending the stairs with a duplicate to the tray now residing in Cliff Clifford’s bedchamber.

Crisis averted. Postponed. But not resolved.

“WE COULD TELL THEM there is a problem with the drains, and they’d die if they remained here,” Thornley said as his small staff sat behind the closed and locked door of his private quarters, out of earshot from the Westham servants who had arrived with the marquis.

It had been a long and sleepless night. A worried one, too.

“Can we do that? I don’t want to do that. Makes me look a poor housekeeper,” Mrs. Timon said, worrying at a thumbnail with her teeth. A splendid cook, Hazel Timon was tall, reed thin, and with a spotty complexion that would make it easy to believe she herself subsisted on stale bread and ditch water…and nail clippings.

“Mrs. Timon, you’re biting again,” Thornley said, pointing a finger at her nasty habit.

“And she’s snuffling again,” Mrs. Timon shot back, folding her hands in her lap as she glared at Claramae, who had been intermittently crying into her apron the whole of the night long.

Riley leaned over to put a comforting arm around the young maid, allowing his hand to drift just a bit too low over her shoulder, which earned him a sharp slap from the girl just as his fingertips were beginning to find the foray interesting.

“No, no, no, we can’t have this,” Thornley said, clapping his hands to bring everyone back to attention. “Quarreling amongst ourselves aids nothing. Think, people. What else can we do?”

“I’d make up some breakfast,” Mrs. Timon offered, “excepting for that Gassie fella took over my kitchens.”

“Gas-ton, Mrs. Timon,” Thornley said absently, staring at the list he’d made during the darkest and least imaginative portions of the night.

The plague. Discarded as too deadly. And where was one to find a plague cart when one needed one? Worse, who would volunteer to play corpse?

Measles? Too spotty by half and, besides, Thornley’s memory had told him that his lordship had contracted the measles as a child, so covering Claramae in red spots wouldn’t have the man haring back to Westham.

A fire in the kitchens? Mrs. Timon would have his liver and lights, and if it got out of hand, half of London could go up in flames. Their situation was desperate, but not dire enough to risk another Great Fire.

What was left?

Thornley’s mind kept coming to the same conclusion.

“We…we could tell ’em the truth, give ’em their money back, and ask ’em very kindly to take themselves off,” Claramae offered weakly, then blew her nose in her apron.

Just what Thornley had been thinking, which was a worriment, if the simple-headed Claramae thought it a good idea.

An expensive silence settled over the room.

Mrs. Timon thought about the locked box in the bottom of her closet. She was a year short of having enough to lease a small cottage by the sea, complete with hiring a local girl as servant of all work, and never cooking another thing for another person. She’d eat twigs before she’d stand over another stove in August.

Riley wondered where and how he’d come up with his share, as he hadn’t saved so much as a bent penny, preferring to wager everything each year on such hopefully money-tripling pursuits as bearbaiting, cockfights, and the occasional dice game in his favorite pub.

Claramae, author of the idea, sat quietly and didn’t think at all, which was all right, because she really wasn’t very good at it anyway.

Which left Thornley.

“I suppose we could. We were overly ambitious in the first place, I realize now. And, as it’s nearly gone seven, and we have had no other idea, I suppose we’ll have to resort to the truth. Come along,” he said, getting to his feet. “The Clifford ladies and the rest will be rising shortly, as is their custom. We must speak to them before they ring for their morning chocolate and alert the other servants to their presence. We’ll also begin with them simply because there are more of them.”

“Yes, but the money…?” Mrs. Timon asked, shuffling her carpet-slippered feet as she followed Thornley.

“As this entire idea was mine, I will be responsible for all remunerations, Mrs. Timon,” Thornley said gamely.

“Yes, but who will pay them?” Riley asked worriedly, trailing along behind, dragging Claramae with him.

EMMA HEARD THE KNOCKING on her bedchamber door, but chose to ignore it. She didn’t want her morning chocolate. She didn’t want morning, as she’d not slept well, a nagging feeling that something might be wrong in the mansion keeping her awake, alert for any sound.

The sound now, however—whispers mixed with whimpering—could not be ignored, so she kicked back the covers and padded to the door of the bedchamber and put her ear to the door.

“Claramae, I said knock and enter. As a man, obviously I can’t go in there, not with Miss Clifford possibly still not dressed for the day.”

“But I don’t…I don’t want to.”

“Stand back, the lot of you. I’ll do it.”

“Riley, stifle yourself.”

“Oh, for goodness’ sakes, I’ll do it.”

Emma jumped back as the latch depressed, and barely missed having the tip of her nose nipped off as the door swung inward and Mrs. Timon stepped inside…followed by a widely grinning Riley, who took no more than two swaggering, arms-waving steps before a long, black-clad arm appeared, grabbed the footman by the collar of his livery and yanked him back out again.

“Miss Clifford?”

“Yes?” Emma said, stepping out from behind the door. “Is something wrong, Mrs. Timon?”

“Well, miss, you could maybe say that, miss…can I fetch your dressing gown?”

Emma frowned at the woman, then retreated to the chair beside her bed, snatched up her dressing gown and slipped into it. “Better, Mrs. Timon?” she asked, tying the sash tightly around her waist.

“Yes, miss, thank you, miss,” Mrs. Timon said. “Your slippers?”

What on earth? Emma located her slippers and put them on.

“Thank you, miss. That should do it,” the cook cum housekeeper cum obscure visitor said, then opened the door once more.

In trooped Riley, still grinning (but no longer swaggering), followed by Thornley, who had his chin lifted so high his only view of the bedchamber could have been the painted ceiling, and Claramae, whose chin could not be lower as she, in turn, inspected the floor.

Emma sat down on the pink-and-white-striped slipper chair, tossed the long, fat single braid over her shoulder and folded her hands in her lap.

She’d been right. Something was wrong.

Her mother had tackled Thornley in the hallways and made a complete cake of herself.

Her grandmother had been caught out snooping in Sir Edgar’s drawers.

Cliff had—well, Cliff could be guilty of most anything.

Miss Emma Clifford did not upset easily. With her family, a person who upset easily would be in her grave, white of hair, wrinkled of skin, and dead of old age at two and twenty, if she did not learn to control her feelings.

Her temper, however, was another thing, and although kept in check for the most part, when unleashed, as her mother would gladly tell anyone, it could be A Terrible Thing. Indeed, Emma was already working up a good scold for whoever had caused what she was sure to be the next very uncomfortable minutes.