This has been one of the major themes of post-war life in Britain, and one that the nation still has not come to terms with. During the war itself, officials were already joking that the USA, the USSR and Great Britain were not really the Big Three, but the Big Two and a Half. In the 1960s, the former American Secretary of State Dean Acheson famously said that ‘Great Britain has lost an empire and not yet found a role’. The nation regained some of its pride in the 1980s and 1990s, during the age of Thatcherism and ‘Cool Britannia’, but at the start of the twenty-first century it once again feels itself in the shadow of others: the USA, China, the European Union.

This is the true meaning of the Bomber Command Memorial, with its heroes staring out between Doric columns like prisoners in a cage. They are a group of heroes who appear to have nothing heroic to do. They have finished their mission, but have been cheated of their glory, and now they merely stand there, gazing across London’s Green Park, waiting stoically to see what new disappointments might be looming on the horizon.

6

Italy: Shrine to the Fallen, Bologna

The themes on display at London’s Bomber Command Memorial are part of a much greater pattern that is evident not only in the UK but all over the world. In the twenty-first century, every nation likes to believe itself a nation of heroes; but deep down, most nations are beginning to think of themselves as victims.

This process has been decades in the making. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, heroism was still in great demand. But in the years since then, many nations have come to realise that heroism comes with responsibilities. For example, the USA, the one undisputed winner of the war, has found itself obliged to act as the world’s policeman ever since. Britain too felt obliged to keep the world’s peace after 1945, despite the fact that it could no longer afford to do so.

There are other dangers, too. Heroes always run the risk of being exposed as the flawed human beings they really are; and, once exposed, they can quickly fall from grace – much as the old Soviet heroes have recently fallen from grace in eastern Europe. In an effort to stave off this trend, some nations have resorted to defending their Second World War heroes with a manic vigour. One need only look at the way that the USA mythologises its ‘greatest generation’, or that Britain continuously mythologises the figure of Winston Churchill, to see how much work it takes to maintain hero status.

Other nations, however, have given up portraying themselves as heroes altogether. Instead they have increasingly begun to choose another motif for their memorials, equally powerful, and equally pure – that of martyrdom. This is a much easier identity to maintain. It allows a nation to keep the moral high ground without having to shoulder any of the work or responsibility for maintaining peace; and it is an easy way to deflect criticism. In the next part of the book I will discuss the growth of victimhood as a national motif, which comes with its own drawbacks and dangers.

First, however, I want to explore one final monument to heroism, which shows a very different side of what it is to be a hero.

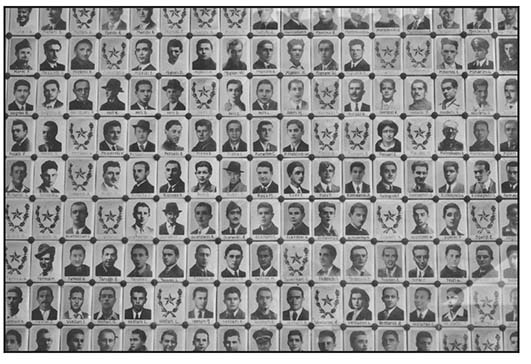

The Shrine to the Fallen in Bologna, Italy, is a much more intimate memorial than any I have described so far. Based on the simplest of ideas, it consists of some 2,000 portraits and names of local resistance fighters attached to the wall of the municipal building in Piazza del Nettuno, right in the centre of the city. This was the site where captured partisans were publicly executed during the war. Since 1945 it has become a commemorative site not only for those who died here, but also for those who died fighting the Nazis and Italian Fascists all over the region.

Unlike any of the other monuments in this book, this one was not erected by the state, or by a museum, or by any other kind of remembrance organisation. It was not planned in advance, but born in a spontaneous burst of emotion. It was put together by local people to commemorate the lives and deaths of those they had known and loved. It highlights something about the war that does not come across in most larger, state-sponsored memorials: the Second World War was not only a titanic conflict between giant armies on the battlefield, it was also an intensely local war fought in the hills and the forests, and on the streets of towns far behind the front lines. The war had a different flavour in Italy from that of Poland or France; and it had a different flavour in Bologna from that of Naples or Milan. The Shrine to the Fallen was not constructed to express national virtues or ambitions; it was simply an expression of local pride, and local loss. It is reminiscent of something that we all do privately in our living rooms at home – display the portraits of those we most love. This is who we are, it says. These people are family.

The war in Italy was much more complicated than it was in other parts of Europe. Italy had begun the war as an ally of Germany, but ended up being occupied by German forces when it tried to change sides in 1943. After the Allies invaded the south, the Germans set up a puppet government under Benito Mussolini in the north, and the country was effectively split in two. In the midst of this upheaval, a resistance movement grew up. All kinds of groups joined the partisans, but the driving force behind it was the Italian Communist Party, which sought not only to liberate the nation from the Germans, but also to overthrow the Fascists who had ruled Italy since the 1920s, and to institute widespread social change in the process.

As a major centre of the Resistance, Bologna suffered more than most places in Italy. In the last year of the war, the region was awash with intrigue and violence. In nearby Marzabotto, an entire village was massacred by the Waffen-SS in reprisal for local resistance activity – at least 770 men, women and children were shot in cold blood, or burned to death in their houses. Within Bologna city centre there were more than forty different public shootings, involving around 140 men and women. Piazza del Nettuno was a favourite spot for both the Nazis and the Italian Fascists to carry out these executions. Between July 1944 and the end of the war at least eighteen people were shot here. Their bodies were left on display as a warning to the local population; and to drive the point home, a sarcastic notice was placed on the wall proclaiming it a ‘place of refreshment for partisans’.

However, if such violence was supposed to deter people from joining the Resistance, it did not work. By the end of the war the Bolognese people had had enough. On 19 April they rose up in insurrection, and within two days had taken control of the city. According to official figures, by this time more than 14,000 local people were actively fighting for the partisans, of which more than 2,200 were women. Bologna was in the vanguard of a nationwide movement: a few days later, on 25 April, insurrection spread to all parts of northern Italy.

As the Germans and their Fascist puppets fled the city, the people of Bologna were at last able to mourn their losses publicly. The families of those who had been executed returned to Piazza del Nettuno and set up a shrine to their loved ones. Someone pushed an old green table against the wall, upon which people could place little mementos, flowers and framed photographs of those who had died. An Italian flag was hung on the wall, and more photographs were pinned to it.

In the coming days, this shrine grew and grew. Within a couple of months there were hundreds of photographs spreading for 20 metres along the wall. It quickly became not only a place of mourning for those who had been killed on this spot, but also a place of respect for all those who had died in the name of freedom. There were photographs and tributes to all kinds of people: teenage boys executed for resistance activities, women in their sixties who had died heroically in combat, men in their prime who had died in training accidents or had been tortured to death by the authorities. The full range of the partisan experience was represented here.

It was not long before the new city authorities decided that the shrine should become a permanent feature affixed to the medieval wall of the Palazzo d’Accursio. In 1955 the paper photographs were taken down and replaced with weatherproof tiles, each one displaying the name or portrait of a single man or woman. Today there are more than two thousand tiles on that wall, along with sixteen larger tiles reproducing photos of the time. It is an enduring reminder of the suffering and bravery of the people of Bologna.

As the saying goes, everything is political. The Shrine to the Fallen may have begun as a simple symbol of mourning; but there was always more to it than that. It was inevitable that it would include some political overtones; after all, it had been built to commemorate those who had died for their beliefs. Political themes were therefore present in the shrine from the beginning, and would continue to characterise it over the following decades.

The liberation of Bologna in April 1945 was a chaotic and violent event. According to Edward Reep, an American war artist who witnessed the liberation of the city, one of the first acts to take place in Piazza del Nettuno in April 1945 was not one of mourning at all, but one of vengeance. Before the shrine was first set up, a Fascist collaborator was shot here: his fresh blood was still visible on the wall. In other words, the political violence that had characterised the war years was not quite over; it was just that the boot was now on the other foot. In the long aftermath of the war, similar violence would continue to rear its head from time to time all over Italy.

The original shrine in 1945

According to Reep, political symbols were incorporated into the shrine even while it was first taking shape:

Within minutes, an Italian flag was hung on the wall, above and to the left of the blood stain … The House of Savoy emblem had been ripped away from the white central panel of the flag; pinned in its place was a stiff black ribbon of mourning. This became a dual gesture: it signified the end of the monarchy and Fascism, and it became a memorial to those who had given their lives in the long struggle for liberation.

It was upon this flag that mourners first pinned their photographs.[fn1]

In the following years, the Shrine became one of many monuments in Bologna dedicated to the partisans. In 1946, a bronze statue of Mussolini on horseback was melted down to create two new statues of Italian Resistance fighters: they can be seen today at Porta Lame, north-west of the city centre. In 1959, an Ossuary to the Fallen Partisans was built in Certosa Cemetery by architect Piero Bottoni, and in the 1970s two more monuments were built: one in Villa Spada, and another at Sabbiuno, just south of the city. In addition, several streets and piazzas were renamed after the war. For example, the piazza named after King Umberto I became ‘Piazza of the Martyrs of 1943–1945’.

All this was part of a deliberate attempt not only to demonstrate the city’s moral and social rebirth after the war, but also to redefine its very identity. Monarchist and Fascist symbols were torn down, and symbols of the Resistance were put up in their place. If Bologna was to be a city of heroes, they were not to be the old, elitist heroes. From now on it would be workers and students who were celebrated – ordinary people, with faces like those on display in Piazza del Nettuno.

Under the gaze of all those dead heroes, the people of Bologna were more or less obliged to follow the future laid out for them by the memory of their wartime struggles. In the first post-war municipal elections, held in March 1946, they elected a member of the Resistance as their mayor. Giuseppe Dozza would lead the city council for the next twenty years; and his party, the Italian Communist Party, would remain the major force in Bolognese politics for most of the rest of the century.

In the 1970s and 1980s the city once again came under attack. During the anni di piombo – the ‘years of lead’ – the whole of Italy became embroiled in political violence. Many other cities suffered terrorist attacks at the hands of the Communist ‘Red Brigades’; but Bologna came under assault from neo-Fascists. In 1980, a bomb was set off at the main railway station, killing eighty-five people and injuring some two hundred more. Two smaller-scale attacks also happened in 1974 and 1984, killing a dozen or so people each time. The reason was clear: Bologna had been targeted because it was a left-wing city.

To commemorate these attacks, a new plaque was put up in Piazza del Nettuno close to the Shrine, listing the names of the dead. Unwittingly, however, the new plaque marked a subtle shift in the city’s memorial landscape. The original Shrine to the Fallen had never given the impression of a people that felt sorry for themselves, despite the terrible atrocities they had suffered during the war. The wording above it states clearly, in large metal letters, that the wartime partisans were heroes who had died in a just cause: ‘for liberty and justice, for honour and the independence of the fatherland’. The wording on the new plaque, however, carried no such message. Here, the dead were simply ‘victims of Fascist terrorism’. They had not died in a cause. There was no semblance of heroism. When the two memorials are taken together, the lines between heroism and victimhood no longer seem so clear-cut. The senseless violence of the 1980s is reflected back in time to the equally senseless violence of the war years, and even the partisans begin to look less like heroes and more like martyrs.

In recent years, there have been even greater shifts in the city’s identity. The old certainties of Bolognese political life have long since broken down: Communism died here, just as it did all over Europe, with the end of the Cold War. Since the turn of the century there has been little continuity between the city’s wartime past and its present: largely speaking, the Communists have given way to the more moderate Social Democrats. The tides of globalisation are also visible, not only in the university, which has always welcomed students from all over Italy and the world, but also in the general population. More than 10 per cent of the people living in Bologna today come from other countries, and that percentage is growing all the time.

In such a world, the 2,000 portraits on Piazza del Nettuno no longer have the power that they once did. They are obviously from a bygone era. Their faces look stiff, formal – nothing like the smiling selfies that today’s generations routinely post on social media. Why should these old portraits be relevant any more? Why should today’s city be held prisoner to their history, and their ideas?

And yet they still dominate the wall of this medieval piazza. Local politicians making their way to and from the town hall must walk past them every day. Students who gather on the steps of the public library sit in their shadow. Like the photographs of long-dead aunts and uncles in countless homes across Bologna, they gaze down on the inhabitants of this left-wing city, silently reminding them of who they are, and where they have come from.

Coda: The End of Heroism

Heroes are like rainbows: they can only really be appreciated from a distance. As soon as we get too close, the very qualities that make them shine tend to disappear.

None of the monuments I have described so far reflect the nuances of historical reality. The greatness of the Russian Motherland was always built on shaky foundations. America’s devotion to its flag, while glorious to Americans themselves, always looked a little dubious to everyone else. Britain needed its famous stiff upper lip not only to win the war but also to weather the disappointments that would follow. And resistance movements – not only in Bologna, but all over Europe and Asia – usually did far more dying than they ever did resisting. But none of this really matters, because these monuments were never meant to express historical reality. They are representations of our mythological idea of what it means to be a hero, that’s all. They are as much expressions of identity as they are of history.

In some ways our monuments to our Second World War heroes seem quite timeless. The values they express – strength, stoicism, brotherhood, virtue – are no different from the values that all societies have held dear since ancient times. But in other ways they seem hopelessly dated: indeed, some of them, like the Bomber Command Memorial in London, already looked old-fashioned from the moment they were first unveiled. It is no coincidence that all the monuments I have mentioned in this section are conventional statues, or photographs, or statues based on photographs. This is the way that heroes are generally commemorated throughout the world. Compared to some of the monuments I will describe later, they are rather unadventurous.

Heroes represent our ideals. They must be brave but gentle, steadfast but flexible, strong but tolerant; they must always be virtuous, always be flawless, always be ready to spring into action; and as our communal champions they must represent all of us, all the time. No individual can possibly live up to such expectations. Neither can any group.

And yet some nations have been bequeathed these responsibilities by history. As the undisputed victor of the Second World War, America has been called upon to act the hero ever since. To a lesser degree, the UK and France have also felt obliged to take a leading role in international affairs, particularly when it comes to their former colonies. Even Russia sometimes feels obliged to live up to its status as a great power. The efforts of these nations are not always appreciated, and unsurprisingly so: no modern-day international policeman can ever live up to the Second World War ideal.

Times change. Values, even timeless values, go in and out of fashion: who today celebrates qualities like stubbornness, inflexibility, or the willingness to endure silently? Inevitably some of the heroes we used to revere seem faintly tragic, or even slightly ridiculous, to modern sensibilities. Communities also change. Our heroes are supposed to represent who we think we are, or at least who we would like to imagine ourselves to be, but when we begin to adopt new political outlooks, or when our communities absorb people of different classes, religions or ethnicities, it becomes hard to identify with the old heroes any longer.

All this highlights a strange paradox: our heroes, who in our minds seem so strong and indestructible, are actually the most vulnerable figures in the historical pantheon. It does not take much to knock them from their pedestals.

There are other, more robust motifs. As I have already hinted, many groups are now much more likely to portray themselves as martyrs than as heroes. In most cases, the groups in question have little choice in the matter: we are all prisoners of our history, and these are the roles that the tragic events of the past have bequeathed them. Nevertheless, as will become clear, martyrdom turns out to be a much stronger identity than heroism ever was. Heroes come and go. But a martyr is for ever.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: