Prisoners of History

The only consolation offered to Russian and other Soviet people was that their country had proven itself at last to be a truly great nation. In 1945, the USSR possessed the largest army the world has ever seen. It dominated not only the vast Eurasian land mass, but also the Baltic and the Black Sea. The Second World War had not only restored the country’s borders, but extended them, both to the west and to the east, and Soviet influence now stretched deep into the heart of Europe. Before the war, the Soviet Union had been a second-rate power, weakened by internal upheaval. After the war, it was a superpower.

The Motherland statue on Mamayev Kurgan was designed to be proof of all this. It was built in the 1960s, when the USSR was at the height of its strength. It stood as a warning to anyone who dared attack the Soviet Union, but also as a symbol of reassurance to the Soviet people. The giant, it declared, would always protect them.

For the Russian citizens who first stood on the summit of this hill with the Motherland statue at their backs, the vistas looked endless. Everything to the west of them for a thousand miles was Soviet territory. To the east they could travel through nine time zones without once leaving their country. Even the heavens seemed to belong to them: the first man in space was a Russian, and the first woman too. It is impossible to look up at the Motherland statue without also gazing beyond, to the endless skies above her.

Since those days, Russia has never stopped building war memorials. Many of them are on a similar scale to those in Volgograd. In 1974, for example, a statue 42 metres (138 feet) high of a Soviet soldier was erected in Murmansk, in memory of the men who died during the defence of Arctic Russia in July 1941. In the early 1980s, when Ukraine was still a part of the Soviet Union, a second Motherland statue was erected in Kiev. (Like the statue on Mamayev Kurgan, it was designed by Vuchetich. Including its plinth, it stands over 100 metres, or around 320 feet, tall.) And in 1985, in celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the end of the war, a 79-metre-high victory monument (around 260 feet tall) was erected in Riga, the capital of Soviet Latvia.

All these statues and monuments were meant to be symbols of power and confidence. But a generation after the Motherland statue in Volgograd was inaugurated, Soviet power began to waver. In the 1980s, Eastern Bloc countries like Poland and East Germany began to pull away from Soviet influence, culminating in the collapse of Communism in those countries in 1989. Then pieces of the Soviet Union itself began to break off: first Lithuania in March 1990, followed in quick succession by thirteen other states in the Baltic, eastern Europe, the Caucasus and central Asia. The giant was crumbling. The dissolution of the USSR was finally announced on 26 December 1991.

The sense of despair felt by many Russians during this period was palpable. Madeleine Albright, America’s Secretary of State at the end of the 1990s, tells the story of meeting a Russian man who complained that ‘We used to be a superpower, but now we’re Bangladesh with missiles.’ For decades, national greatness had been the only consolation for all the loss that men like him had suffered throughout the century. Now this too had been taken away.

In such an atmosphere, Russia’s gargantuan war memorials began to look less like symbols of power, and more like Ozymandias in the famous poem by Shelley: relics of past glories, destined to be swallowed, slowly but surely, by the sands of time. But this did not stop the Russian authorities from building them. On the contrary: Russia has never stopped celebrating the glories of the Second World War. In 1995, for example, a brand new ‘Museum of the Great Patriotic War’ was opened in Moscow. In front of it stands a monument that is even taller than the statue on Mamayev Kurgan: in fact, standing at 141.8 metres (or 465 feet) tall, it is the tallest Second World War memorial anywhere in the world. Other monuments followed. In April 2007, Belgorod, Kursk and Oryol were declared ‘Cities of Military Glory’ because of the role they had played during the war, and brand new obelisks were erected in each location. The following October, five more cities were given the title, and five more obelisks erected. Within just another five years, more than forty cities across Russia were honoured in the same way, with brand new monuments springing up from Vyborg to Vladivostok.

Why do the Russians continue to commemorate the war in this manner? More than seventy-five years have passed since the final days of the conflict. Is it not time to lay it to rest?

There are a couple of possible explanations for the country’s seemingly limitless addiction to massive Second World War monuments. The first is that the trauma caused by the war was so great that Russians simply cannot forget it. They feel compelled to tell the stories of the war again and again, in the same way that individuals who have experienced trauma often have flashbacks. These new memorials, each seemingly bigger than the last, are Russia’s way of coming to terms with its past.

I’m sure that this is true, but it is also a little simplistic. For example, it does not explain why the memorials are growing and replicating now more than ever. Is there something about life in Russia today that triggers these concrete flashbacks? I can’t help feeling that there must be a renewed sense of instability, or vulnerability, which is driving Russians to insist ever more stridently upon their wartime heroism. In other words, the monuments that they are erecting today have as much to do with the present as with the past.

Or perhaps this is simply about nation-building. Russia is not the country that it once was. It has lost an empire, and not yet found a new role for itself in the world. For many Russians, the building of war memorials serves as a reminder of the status that their country once had, and perhaps also gives a sense of hope that, one day soon, Russia might rise again. The bigger the monument, the greater the sense of pride – and the greater the nostalgia. The glorification of the war has become a central pillar of Vladimir Putin’s programme to forge a new sense of national identity.

This too can be felt at Mamayev Kurgan. During the 1990s, when Russian power was crumbling, the Motherland statue also began to fall apart. Decaying pipes around the ‘Lake of Tears’ began to leak water into the hill around the statue, making the soil unstable. By the year 2000, deep cracks had begun to appear in the statue’s shoulders. A few years later, reports emerged that it was listing 20 centimetres to one side. The cash-strapped Russian government kept promising to pay for reconstruction work, but the money never arrived. Nobody knew whether this official neglect was due to Russia’s new-found poverty, or its new-found ambivalence towards its Soviet past.

In recent years, however, the monument has had a new lease of life. When I visited in 2018, the Motherland statue had just been repaired. The other monuments in downtown Volgograd had also been given a facelift, and the whole of the city’s Victory Park was closed for refurbishment. In the central square, which is named the ‘Square of the Fallen Heroes’, school children were practising their marching for a ceremony to honour the Stalingrad dead.

There is pride here, and sorrow, in equal measure. When you climb the hill today, you see people from all over Russia who have come to this place to pay their respects. Families bring children to teach them about the heroism of their great-grandfathers. Young women pose for photos in front of the Motherland statue, and carry red carnations to lay at the feet of the monuments. Military men come in full dress uniform, their medals clanking as they climb the steps.

None of these people can escape the history that has forged them, nor the longing for greatness that has been so integral to their nation’s consciousness since 1945. For better or worse, they continue to live in the shadow of the great statue that stands on top of the hill.

The ‘Four Sleepers’ monument in 2010, before it was taken down

2

Russia and Poland: ‘Four Sleepers’ Monument, Warsaw

Every nation takes pride in its heroes. The monuments we create to those heroes have a special place in our hearts, because they are representative of all we hold dear: they show us at our very best, with all our most attractive qualities on display. But how we would like to think of ourselves is not always the same as how we really are. And neither is it the same as how we are viewed by others. Our monuments may look glorious to us, but to other people, with other values, they may look distinctly unheroic, even grotesque.

The Russian people are rightly proud of their Second World War heroes, but one does not have to travel far from Russia to find a very different narrative about the role played by that country during the conflict. In neighbouring states like Ukraine and Poland, the Russians are often regarded not as heroes but as colonisers. This narrative too is played out in the story of Europe’s monuments. And one monument in particular shows how polarised our different versions of history have become.

* * *

The Monument to Brotherhood in Arms was built in 1945, and erected in Warsaw at the end of that year. It was designed by a Soviet army engineer, Major Alexander Nienko, but was constructed by a group of Polish sculptors. It depicted three larger-than-life soldiers on top of a six-metre plinth (around 20 foot), striding forward, weapons in hand. Standing at the corners of the plinth were four further statues – two Soviet soldiers and two Polish ones – their heads bowed in sombre contemplation. As a result of wartime shortages, the original statues were made of painted plaster; but two years later they were replaced with bronze casts made from melted-down German ammunition. On the plinth itself were inscribed the words: ‘Glory to the heroes of the Soviet Army, comrades in arms, who gave their lives for the freedom and independence of the Polish nation’.

This monument was meant to depict a new era of friendship between Poland and the Soviet Union. The two countries had shared an extremely difficult history, stretching right back into Tsarist times. They had actually begun the war on opposite sides: the USSR had initially allied itself with Hitler, and had taken part in the invasion of Poland in 1939. But two years later, when the Nazis had turned against them, the Soviets had sought to build a new relationship with the Poles. They released Polish prisoners and exiles, and allowed them to reform an army. As a consequence, some 200,000 Polish troops fought alongside their former enemies in 1945. The liberation of Warsaw was carried out by Polish soldiers and Soviet soldiers fighting together.

The Monument to Brotherhood in Arms therefore fulfilled several functions at once. It was an acknowledgement of the genuine debt that Poland owed to the Soviets: had it not been for the sacrifices of the Red Army, Poland would not even have existed in 1945. It promoted hopes for the future: if Poland and the USSR could collaborate in wartime, then why not in peacetime too? And, of course, it was a work of political propaganda. The soldiers who stand on the top of the plinth are Soviets, with the Polish soldiers below them: from now on, as far as the Soviets were concerned, that would be the correct hierarchy.

This was the first monument to be built in Warsaw after the war, but it was soon followed by others. All over the country, similar memorials began to appear. There were sculptures celebrating Polish-Soviet friendship, obelisks commemorating their joint victory over the Nazis, plaques dedicated to their common war dead, tombs, cemeteries, everlasting flames. According to a list drawn up in 1994, around 570 monuments dedicated to fallen Soviet soldiers were built across Poland in the aftermath of the war. This was all part of an official drive to build on the wartime collaboration between Poland and the USSR and forge a new, Communist future together.

Unfortunately, none of these memorials inspired anything like the love and devotion that similar memorials did in the USSR. Since they celebrated the exploits and sacrifices of foreign people, they were not monuments in which Poles themselves could take much personal pride – at most they were monuments to gratitude and friendship. But when that gratitude ran dry and that friendship turned sour, the monuments began to take on an altogether darker meaning.

Most Poles knew very well where they stood in any partnership with the USSR. They saw these symbols of power and glory and began to suspect that it was not only the Nazis who had been ground beneath the wheels of Soviet greatness. Soon they began to take out their frustrations on those symbols. Soviet monuments were often vandalised, defaced, and covered with nationalist graffiti. They were given derogatory nicknames based on popular memories of the way that Soviet soldiers had behaved during the liberation: names like ‘the looters’ memorial’ or ‘the tomb of the unknown rapist’. The Monument to Brotherhood in Arms in Warsaw was no exception. People joked that the statues at each corner were not hanging their heads in mourning, but because they had fallen asleep on duty. Thereafter, the memorial was popularly known as Czterech Śpiących, or ‘The Four Sleepers’.[fn1]

Over the next forty years, the monument continued to stand on its plinth in Warsaw’s Praga district. It was occasionally used as a site of remembrance for the war or as a venue for celebrating the more general victory of Communism in Europe. On the thirty-fifth anniversary of the October Revolution, for example, the Warsaw Philharmonic played here, while officials laid flowers at the foot of the monument.

But in 1989, everything changed. During that extraordinary year, Communist governments across eastern Europe began to collapse. The Berlin Wall was breached, dictatorships were toppled, and Soviet monuments everywhere were torn down. For a while the world’s newspapers regularly carried photographs of statues falling: Romania’s Petru Groza, Albania’s Enver Hoxha, Poland’s Bolesław Bierut and, all over Europe, Lenin after Lenin after Lenin.

Remarkably, the ‘Four Sleepers’ monument in Warsaw survived these years unscathed. In 1992 the local authority briefly considered dismantling it; but the idea caused such disagreement – especially when one of the artists who had helped to create it, Stefan Momot, stood up in a meeting to defend it – that the proposal was eventually dropped.

Fifteen years later, however, another attempt was made to remove it, this time on practical grounds. Transport experts were considering the creation of a new tram stop on the exact location of the monument as part of a city-wide transport improvement plan. The tram idea was eventually abandoned, but four years later another transport plan insisted that the ‘Four Sleepers’ had to be moved to make way for a new underground station. The authorities promised that it would be put back just as soon as the construction of the station was finished. So, in 2011, it was taken down and transported to a conservation workshop in Michałowice.

This, it appeared, was exactly the opportunity that opponents of the memorial had been waiting for. Members of the Law and Justice Party, a right-wing populist movement, were especially vocal. They argued that the monument should never be allowed back to the square, on the grounds that it glorified a foreign power that had subjugated Poland for more than forty years. They called the ‘Four Sleepers’ a monument to shame, which painted the Polish people as passive bystanders in a Soviet story. It, and all monuments like it, was an insult to Poland, and a falsification of Polish history.

Other figures joined in with the vilification of the monument. Various historians and former dissidents pointed out that the ‘Four Sleepers’ stood at the centre of a district that had been filled with institutions of state repression. The Warsaw Office of Public Security, a provincial detention centre, the headquarters of the NKVD and a city prison had all stood within 100 metres (328 feet) of the monument. ‘In each of these places “the enemies of the state” … were interrogated and tortured,’ wrote Dr Andrzej Zawistowski of the Polish Institute for National Remembrance. For such people, the monument represented not only the prison of history, but actual prisons, where real people had been persecuted.

And yet many others were willing to defend the monument. Socialist politicians argued that the memorial did not glorify Stalinism at all, or commemorate the Soviet leaders who repressed Poland, but merely the ordinary foot-soldiers, who were often conscripted into the Red Army by force. Ageing veterans pointed out that 600,000 of these ‘Sachas and Vanyas’ had died on Polish soil, and that Polish soldiers were also represented on the monument.

The controversy raged for four years, and involved countless articles in the press, petitions, media debates, demonstrations and acts of vandalism. In 2013, the local authority carried out an opinion poll about whether the monument should stay or go. The results seemed quite emphatic: only 8 per cent wanted the monument to be destroyed, and 12 per cent wanted it moved to a far-off location, but 72 per cent wanted it to be put back in the square. Opponents countered that the sample size had been less than a thousand, and that most people only wanted to keep the monument because it was something they had grown used to. If Poland was to look to the future it needed to free itself from this toxic history.

In the end, it was the nationalist faction that won out. In 2015, the city council announced that it would not return the ‘Four Sleepers’ monument to Wileński Square after all. Three years later, it was announced that it had been donated to a new Museum of Polish History in the north of the city. According to museum staff, it will finally be on display in 2021 – some ten years after it was removed from its original site.

What is a hero? What is a hero for? Russians see the deconstruction of their war heroes as a personal affront, but heroes are much more than mere representations of actual people; they are also representations of ideas. If you no longer agree with the ideas, then perhaps the heroes must come down.

For Russians, statues like the ‘Four Sleepers’ represent bravery, liberation, brotherhood – and, of course, greatness. But for Poles and other eastern Europeans, they represent something entirely different: subjugation, humiliation, repression. The truth is that they represent both sets of ideas at the same time, but the emotions surrounding these monuments are so strong that many people are simply not willing to entertain such ambiguity.

The ‘Four Sleepers’ monument is a single casualty in a war over the memory of 1945 that has swept across Poland in recent years. Dozens of Soviet war monuments were pulled down or destroyed in the exuberant atmosphere of 1989, and dozens more were removed by local councils in the years that followed. In 2017, the national government finally embarked on an official programme to remove those that remained. This went against an agreement made in 1994 between Russia and Poland to respect one another’s ‘places of memory’. But the Polish government, which by now was dominated by the populist Law and Justice Party, stated that all they were really doing was removing the symbols of foreign power from their towns and cities: they promised not to touch any memorials that marked genuine burial places.

It is not only Poland that has embarked on such a programme. In 2015, for example, the Ukrainian government also passed a law aimed at the complete de-Sovietisation of the country. It included the removal of all Communist symbols and statues of Communist figures, and the renaming of thousands of streets, towns and villages. This was carried out quite quickly. By 2018, the director of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, Volodymyr Vyatrovych, was able to announce that the de-Communisation of the nation had been achieved.

Similar controversies have hit Soviet war memorials all over eastern and central Europe. The Monument to the Heroes of the Red Army in Vienna is regularly vandalised. The Monument to the Soviet Army in Sofia has repeatedly been daubed with paint – sometimes in jest, but more often in protest over recent actions by the Russian government. The Victory Monument in Riga was bombed in 1997 by a far-right Latvian nationalist group, and since then veterans of the Second World War have repeatedly called for it to be taken down. In Estonia, in 2007, the Bronze Soldier memorial to the ‘liberators of Tallinn’ was removed from the city centre and relocated in the military cemetery a few kilometres away, sparking two days of protest by Tallinn’s ethnic Russian minority.

Many people across eastern Europe regard this iconoclasm as the only way to free their countries from the burden of their Communist past. Given all that they have suffered, this is quite understandable; but, as any psychologist will tell you, history is not so easily escaped. As will become apparent, these people seem to be deconstructing one prison only to build themselves another.

In the meantime, most ordinary Russians struggle to understand why they should be so hated in eastern Europe. They see the dismantling of monuments to their war heroes as a personal affront. But since they no longer rule in eastern Europe, there is nothing they can do about it.

3

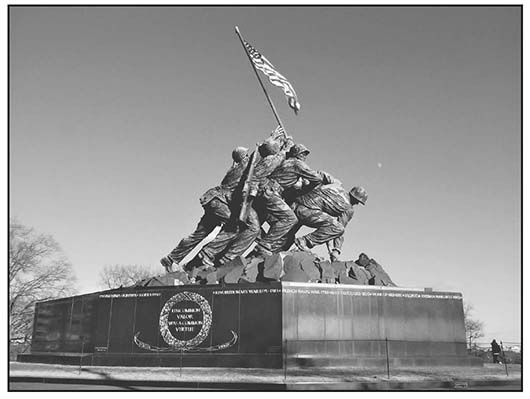

USA: Marine Corps Memorial, Arlington, Virginia

If Russia’s monumental heroes reflect that nation’s longing for greatness, what of the other post-war superpower? How do Americans tend to view their heroes?

In my working life, I often travel to different parts of the world giving lectures about the Second World War. In one particular lecture I talk about America’s mythology of heroism. It is a subject that fascinates me because, to a European like me, it seems so extreme. Americans sometimes seem to regard their war heroes as if they were not human at all, but figures from legend, or even saints. President Reagan spoke of them as a Christian army, impelled by faith and blessed by God. President Clinton called them ‘freedom’s warriors’, who had immortalised themselves by fighting ‘the forces of darkness’. TV journalist Tom Brokaw famously proclaimed them ‘the greatest generation any society has ever produced’. How can any real-life soldier or veteran possibly live up to such expectations?

I have noticed that reactions to my lecture differ depending on where I deliver it. Whenever I’m in America, my audience tends to listen respectfully in silence: some of them agree with me, and some of them don’t. But when I give this lecture anywhere in Europe, the audience tends to snigger. At one point, when I quote at length from a speech given by Bill Clinton to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of VE Day, they sometimes laugh out loud. American rhetoric, to many Europeans, sounds ridiculous.

It is always nice to get a laugh when you’re speaking; but there is something about this particular laughter that worries me. Europeans often make fun of America’s insular view of the world, but they themselves are often equally ignorant of America. They don’t mean to be disrespectful; they simply can’t quite believe that anyone is serious when they speak about their war veterans in this way. But Americans are deadly serious. In the American consciousness, the role that their soldiers played during the Second World War has come to represent everything that is best about their country.

This gulf in understanding between Europeans and Americans is immediately apparent as soon as one looks at their war memorials. America makes monuments to its heroes; Europe much more often makes monuments to its victims. American monuments are triumphant; European ones are melancholy. American monuments are idealistic, while European ones – occasionally, at least – are more likely to be morally ambiguous.