Prisoners of History

PRISONERS OF HISTORY

WHAT MONUMENTS TO THE SECOND WORLD WAR TELL US ABOUT OUR HISTORY AND OURSELVES

Keith Lowe

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Keith Lowe 2020

Cover design by Ellie Game

Keith Lowe asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008339548

Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008339562

Version: 2020-03-27

Dedication

For Creo

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

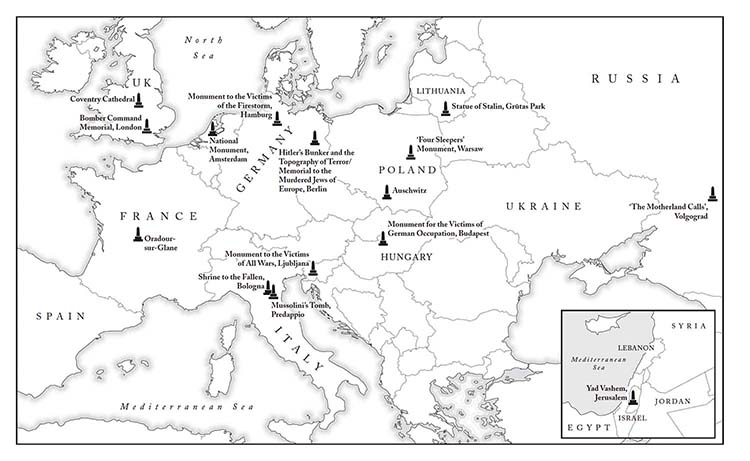

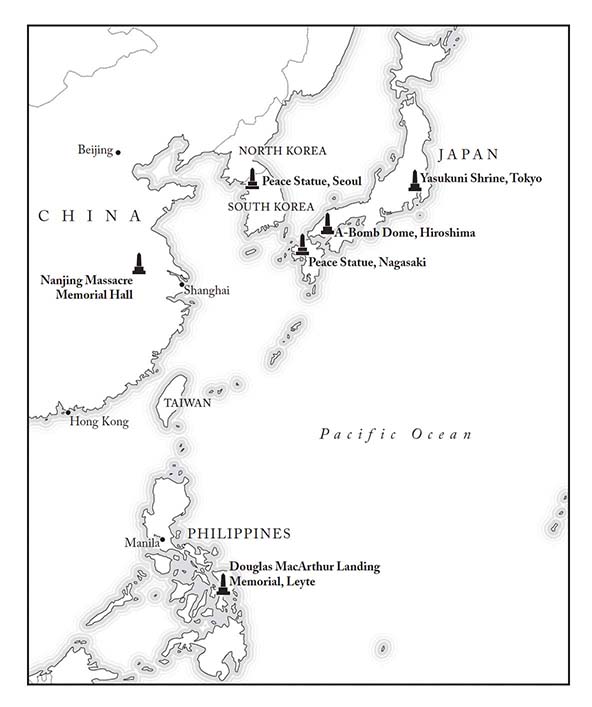

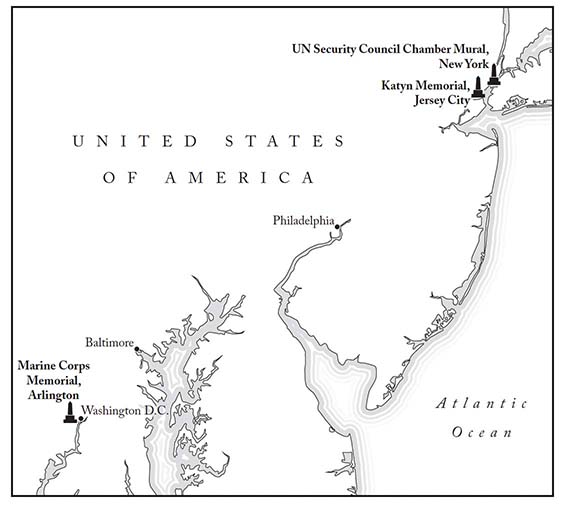

Maps

Introduction

Part I – Heroes

1 Russia: ‘The Motherland Calls’, Volgograd

2 Russia and Poland: ‘Four Sleepers’ Monument, Warsaw

3 USA: Marine Corps Memorial, Arlington, Virginia

4 USA and the Philippines: Douglas MacArthur Landing Memorial, Leyte

5 UK: Bomber Command Memorial, London

6 Italy: Shrine to the Fallen, Bologna

Coda: The End of Heroism

Part II – Martyrs

7 Netherlands: National Monument, Amsterdam

8 China: Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall

9 South Korea: Peace Statue, Seoul

10 USA and Poland: Katyn Memorial, Jersey City

11 Hungary: Monument for the Victims of German Occupation, Budapest

12 Poland: Auschwitz

Part III – Monsters

13 Slovenia: Monument to the Victims of All Wars, Ljubljana

14 Japan: Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo

15 Italy: Mussolini’s Tomb, Predappio

16 Germany: Hitler’s Bunker and the Topography of Terror, Berlin

17 Lithuania: Statue of Stalin, Grūtas Park

Coda: The Value of Monsters

Part IV – Apocalypse

18 France: Oradour-sur-Glane

19 Germany: Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin

20 Germany: Monument to the Victims of the Firestorm, Hamburg

21 Japan: A-Bomb Dome, Hiroshima, and Peace Statue, Nagasaki

Part V – Rebirth

22 United Nations: UN Security Council Chamber Mural, New York

23 Israel: Balcony at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

24 UK: Coventry Cathedral and the Cross of Nails

25 European Union: Liberation Route Europe

Conclusion

Footnotes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Picture Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Maps

Introduction

In the summer of 2017, American state legislators began removing statues of Confederate heroes from the streets and squares outside public buildings. Nineteenth-century figures like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, who had fought for the right to keep black slaves, were no longer considered suitable role models for twenty-first-century Americans. And so they came down. All across America, to a chorus of protest and counter-protest, monument after monument was removed.

There was nothing unique about what happened in America: elsewhere, other monuments were also coming down. In 2015, after the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes from outside the University of Cape Town, there were calls for the elimination of all symbols of colonialism across South Africa. Soon the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ campaign spread to other countries around the world, including the UK, Germany and Canada. In the same year, Islamic fundamentalists began destroying hundreds of ancient statues in Syria and Iraq on the grounds that they were idolatrous. Meanwhile, the national governments of Poland and Ukraine announced the wholesale removal of monuments to Communism. A wave of iconoclasm was sweeping the world.

I watched all this happening with great fascination, but also with a certain incredulity. When I was growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, such occurrences would have been unthinkable. Monuments everywhere were regarded merely as street furniture: they were convenient places to meet and hang out, but few people paid them much attention in themselves. Some were statues of forgotten old men, often with strange headgear and improbable moustaches; others were abstract shapes made of concrete or steel; but either way we did not really understand them. There was certainly no point in calling for their removal, because the majority of people did not care enough about them to make any kind of fuss. But in the past few years, objects that were once all but invisible have suddenly become the centre of attention. Something important seems to have changed.

At the same time as tearing down some of our old monuments, we continue to build new ones. In 2003, the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue in central Baghdad became one of the defining images of the Iraq War. But within two years of the statue’s destruction, a new monument had taken its place: a sculpture of an Iraqi family holding aloft the sun and the moon. For the artists who designed it, the monument represented Iraq’s hopes for a new society characterised by peace and freedom – hopes that were almost immediately dashed in the face of renewed corruption, extremism and violence.

Similar changes are taking place all over the world. In America, statues of Robert E. Lee are gradually being replaced by monuments to Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King. In South Africa, the statues of Cecil Rhodes have come down, and monuments to Nelson Mandela have gone up. In eastern Europe, statues of Lenin and Marx make way for depictions of Thomas Masaryk, Józef Piłsudski and other nationalist heroes.

Some of our newest monuments are truly vast in scale, especially in parts of Asia. At the end of 2018, for example, India unveiled a brand new statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who was an important figure in the nation’s independence movement during the 1930s and 1940s. Standing at 182 metres (almost 600 feet), it is now the tallest statue in the world. To create such gigantic structures, at such huge cost, implies an incredible level of self-confidence. These are not temporary structures: they have been designed to last hundreds of years. And yet who is to say that they will fare any better than the statues of Lenin or Rhodes or any of the other figures that once seemed so permanent?

It seems to me that several things are going on here at once. Monuments reflect our values, and every society deceives itself that its values are eternal: it is for this reason that we cast those values in stone and set them upon a pedestal. But when the world changes, our monuments – and the values that they represent – remain frozen in time. Today’s world is changing at an unprecedented pace, and monuments erected decades or even centuries ago no longer represent the values we hold dear.

The debates currently taking place over our monuments are almost always about identity. In the days when the world was dominated by old white men, it made sense to raise statues in their honour; but in today’s world of multiculturalism and greater gender equality, it is not surprising that people are beginning to ask questions. Where are all the statues of women? In a country like South Africa, with its majority black population, why should there be so many statues of white Europeans? In the USA, which has a population as diverse as any on the planet, why is there not more diversity on display in its public spaces?

But beneath these debates lies something even more fundamental: we can’t seem to make up our minds what role our communal history should play in our lives. On the one hand we see history as the solid foundation upon which our world has been built. We imagine it as a benign force, offering us opportunities to learn from the past and progress to our future. History is the very basis of our identity. But on the other hand we view it as a force that stultifies us, holding us hostage to centuries of outdated tradition. It leads us down the same old paths, to make the same mistakes again and again. When left unchallenged, history can ensnare us. It becomes a trap, from which escape seems impossible.

This is the paradox that lies at the heart of our society. Every generation longs to free itself from the tyranny of history; and yet every generation knows instinctively that without it they are nothing, because history and identity are so intertwined.

This book is about our monuments, and what they really tell us about our history and identity. I have picked twenty-five memorials from around the world which say something important about the societies that erected them. Some of these memorials are now massive tourist attractions: millions of people visit them every year. Each of them is controversial. Each tells a story. Some deliberately try to hide more than they reveal, but in doing so show us more about ourselves than they ever intended. What I most want to demonstrate is that none of these monuments is really about the past at all: rather, they are an expression of a history that is still alive today, and which continues to govern our lives whether we like it or not.

The monuments I have chosen are all dedicated to one period in our communal past: the Second World War. There are many reasons for this, but the most important is that, of all our memorials, these are the only ones that seem to have bucked the current trend of iconoclasm. In other words, these monuments continue to say something about who we are in a way that so many of our other monuments no longer do.

Very few war monuments have been torn down in recent years. In fact, quite the opposite has happened: we are building new war memorials at an unprecedented rate. This is not just the case in Europe and America, but also in Asian countries like the Philippines and China. Why should this be? It is not as if our war leaders were any less controversial than some of the figures whose statues have recently been taken down. British and French leaders were just as much champions of colonialism as Cecil Rhodes ever was; American leaders still presided over a racially segregated army; and men from all the Allied forces engaged in acts that would now be considered war crimes. Their attitudes towards women were not always enlightened either. One of our most famous images of the end of the war, Life magazine’s iconic photograph of a sailor kissing a nurse in New York’s Times Square, celebrates what we now know to be a sexual assault. Our collective memory of the Second World War seems to be able to skip over these issues in a way that our memory of other periods can’t.

In order to get to the bottom of these questions, I have divided our Second World War monuments into five broad categories. In the first part of the book I will look at some of our most famous monuments to the heroes of the war. I will show how these are the most vulnerable of all our Second World War memorials, and the only ones that show any sign of being toppled or removed. Part II will explore our memorials to the martyrs of the war, and Part III will look at some of the memorial spaces that have been carved out for the war’s main villains. The interplay between these three categories is as important as each category itself: the heroes cannot exist without the villains, and neither can the martyrs. In Part IV I will describe memorials to the apocalyptic destruction of the war; and in Part V I will describe some of those to the rebirth that came afterwards. These five categories reflect and reinforce one another. They have created a kind of mythological framework that protects them from the iconoclasm that has ripped through other parts of our collective memory.

I have tried to include a wide variety of monuments, if only to represent the sheer diversity of places that have been used to contain our memories of the past. So I will describe not only figurative statues and abstract sculptures, but also shrines, tombs, ruins, murals, parks and architectural features. Some of the monuments I have chosen were created in the immediate aftermath of the war, while others are much newer – indeed, some are still under construction as I write. Some have an intensely local meaning, while others are of national or even international significance. I have tried to include monuments from many different parts of the world – so, for example, I have included memorials in Israel, China and the Philippines as well as those in the UK, Russia and the USA.

There are great advantages in writing about a period that everyone understands – or, at least, thinks they understand. The Second World War affected every corner of the globe, and most nations around the world commemorate it in one way or another. It is a great cultural equaliser. And yet, as will quickly become apparent in this book, the war is remembered in vastly different ways in different nations. What better way is there to understand the differences between us and our neighbours than to be confronted by our conflicting views on something that we always thought was a shared experience?

Lastly, I have concentrated on Second World War monuments quite simply because of their quality. We sometimes tend to think of monuments as solid, grey, boring, but the sculptures in this book are some of the most dramatic and emotive pieces of public art anywhere in the world. Beneath all the granite and bronze is a mix of everything that makes us who we are – power, glory, bravery, fear, oppression, greatness, hope, love and loss.

We celebrate these and a thousand other qualities in the anticipation that they might free us from the tyranny of the past. And yet, through our desire to immortalise them in stone, they inevitably end up expressing the very forces that continue to keep us prisoners of our history.

We live today in an age of scandal. Our media is so often dominated by stories of corruption among our politicians, our business and religious leaders, our sports stars and screen idols that sometimes it can feel difficult to believe in heroes any more.

It has not always been like this. According to popular memory at least, we once knew exactly who our heroes were. In 1945 we built monuments to the men and women who fought for us in the Second World War, and we continue to build such monuments even today. These monuments speak to us of a simpler time, when people knew right from wrong, and were willing to do their duty for the sake of a greater good.

But how accurate are these memories? Were our heroes really any stronger, braver, or more dutiful than we ourselves are? If we subjected them to the same scrutiny that our politicians and celebrities receive today, would we still be able to see them as heroes?

Our veneration of the Second World War generation says a great deal about how we view our history, and the hold that it still has over us today. In the following pages I will take a look at some of our monuments to heroism around the world, and ask what they say not only about the past, but also about today’s values and ideals. I will also explore what happens when those values change over time. Can our heroes ever live up to our expectations? And what happens when our cosy memories of the past clash with a much colder historical reality?

1

Russia: ‘The Motherland Calls’, Volgograd

The Second World War was probably the greatest human catastrophe the world has ever seen. Historians have always struggled to find words that can convey even a glimpse of its total scale. We give endless statistics – more than 100 million soldiers mobilised, more than 60 million people killed, more than $1.6 trillion squandered – but such numbers are so large that they are meaningless to most of us.

Monuments, memorials and museums do not rely on statistics: they find other ways to suggest the scale of wartime events. A single well-chosen symbol can often hint at this far better than any words. For example, who can look at the mountain of shoes on display in the Holocaust museum at Auschwitz–Birkenau without imagining the host of corpses from which those shoes were stolen? Sometimes even a tiny object can bring to mind something gigantic. In the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum there is a display of clocks and watches that all stopped at the exact moment of the atomic blast. The atom bomb, they seem to say, was so great that it had the power to stop time.

But perhaps the most effective way that memorials convey the vastness of wartime events is also the simplest: through their own sheer size. Many of the memorials in this book are larger than life. Some are truly gigantic. There is a simple rule of thumb that holds true for most of them: the bigger the event being commemorated, the bigger the monument.

This chapter tells the story of one of the largest of them all: the huge statue that stands on top of Mamayev Kurgan, in the city of Volgograd in Russia. Its size tells us a great deal – not only about the Second World War, but also about the Russian psyche, and the bonds that continue to hold it prisoner.

Mamayev Kurgan is not the site of a single monument, but of a complex of monuments, each more gigantic than the last. The first time I came here, I felt I was entering a realm of titans. At the foot of the hill stands a huge sculpture of a bare-chested man clutching a machine gun in one hand and a grenade in the other. He seems to rise out of the very rock, torso rippling, as tall as a three-storey building. Beyond him, on either side of the steps that lead to the summit, are relief sculptures of giant soldiers springing out of the ruined walls as if in the midst of battle. Farther up the hill is the gigantic figure of a grieving mother, more than twice the size of my house. She is hunched over the body of her dead son, sobbing into a large pool of water, called the ‘Lake of Tears’.

The dozens of statues arranged in this park are all giants: not one of them is under six metres (20 feet) tall, and some of them depict heroes three or four times that size. And yet they are dwarfed by the single statue that rises above them all, on the summit of the hill. Here, overlooking the Volga, stands a colossal representation of Mother Russia beckoning to her children to come and fight for her. Her mouth is open in battle cry, her hair and dress fluttering in the wind; and in her right hand she holds a vast sword pointing up into the sky. From her feet to the tip of her sword she stands 85 metres (280 feet) high. She is nearly twice as tall, and forty times as heavy, as the Statue of Liberty in New York City. When she was first unveiled in 1967, she was the largest statue in the world.

This memorial, entitled ‘The Motherland Calls!’, is one of Russia’s most iconic statues. It was the creation of Soviet sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich, who spent years designing and building it. It contains around 2,500 metric tonnes of metal and 5,500 tonnes of concrete. The sword alone weighs 14 tonnes. So huge was the statue that Vuchetich was obliged to collaborate with a structural engineer, Nikolai Nikitin, to ensure that it did not collapse under its own weight. Holes had to be drilled into the sword to reduce the threat of the wind catching it and causing the whole structure to sway.

Were this monument in Italy or France it would appear absurdly grandiose, but here on the banks of the Volga, in the city that was once called Stalingrad, it feels quietly appropriate. The battle that took place here in 1942 dwarfs anything that happened in the West. It began with the greatest German bombardment of the war, and progressed with attacks and counterattacks by more than a dozen entire armies. Within the city itself, soldiers fought from street to street, and even from room to room, in a landscape of shattered houses. Over the course of five months around two million men lost their lives, their health or their liberty. The combined casualties of this one battle were greater than the casualties that Britain and America together suffered during the whole of the war.

As one stands on the summit of Mamayev Kurgan in the shadow of the gigantic statue of the Motherland, one can feel the weight of all this history. It is oppressive even for a foreigner. But for many Russians this place is sacred. The word ‘Kurgan’ in Russian means a tumulus or burial mound. The hill is an ancient site dedicated to a fourteenth-century warlord, but in the wake of the greatest battle of the greatest war in history, it carries a new symbolism. This place was one of the major battlegrounds of 1942, and an unknown number of soldiers and civilians are buried here. Even today, when walking on the hill, it is possible to find fragments of metal and bone buried in the soil. The Motherland statue stands, both figuratively and literally, upon a mountain of corpses.

The scale of the war in Russia is one reason why the monuments on Mamayev Kurgan are so huge, but it is not the only reason – in fact, it is not even the main reason. The statues of muscular heroes and weeping mothers might be huge, but it is the giantess on the summit of the hill that dominates them all. It is important to remember that this is a representation not of the war, but of the Motherland. Its message is simple: no matter how great the battle, and no matter how great the enemy, the Motherland is greater still. Her colossal size is supposed to be a comfort to the struggling soldiers and weeping mothers, a reminder that for all their sacrifice, they are at least a part of something powerful and magnificent. This is the true meaning of Mamayev Kurgan.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the people of the Soviet Union had little to console them. Not only were they traumatised by loss, but they also faced an uncertain future. Russians did not benefit economically from the war as the Americans did: the violence had left their economy in ruins. Nor did Russians win any new freedoms: despite widespread hopes of a political thaw after 1945, Stalinist repression soon started up all over again. Life in Russia after the war was grim.