По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

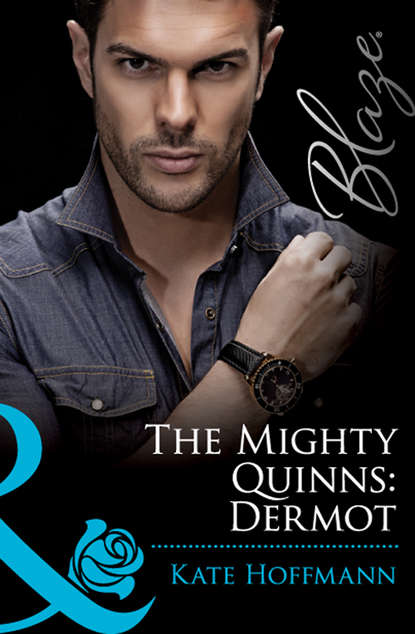

The Mighty Quinns: Dermot

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Sometimes. But just walk in there like you know what you’re doing. Show them who is boss.”

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” he said.

“Charm them like you charmed me,” Rachel suggested.

“And how did I charm you?” he asked, leaning closer.

“Talk sweet to them. Soft. Smile a little.”

Rachel ushered him inside the gate, then closed it behind him. The goats surrounded him and he held up his arms as they nudged at his legs. When he spotted Lady, Dermot gradually worked his way over to her and clipped the lead on her collar. “All right, now what?”

“Now lead her to the gate and the rest of the goats will follow.”

He did as he was told, and before long they were walking down the lane between the paddocks, chatting about his first success as a dairyman.

“Why do they follow?” he asked.

“They know they’re going to get fed.”

“Haven’t they been eating all day?”

“Yeah, but they get the good stuff in the barn.”

“Steak and potatoes?”

“Corn and some pellet feed.”

“Yum,” Dermot said. “Are we having the same for dinner?”

“I think I can scratch up something a little better. But we still have a lot of work to do before we eat.”

“I can handle it,” he said. “I’ve got Lady following me. How much harder can it get?”

DERMOT COULDN’T remember the last time he’d been so exhausted. Once the goats got into the milking shed, the work was nonstop for three solid hours. He barely had a chance to take a breath before Rachel or Eddie was showing him something else that had to be done. Benny, the little black goat, was constantly underfoot, nibbling on Dermot’s jeans and the hem of his T-shirt.

Rachel explained that it normally took her four hours to do the milking on her own, but once he got up to speed, she expected they’d be able to do the entire herd in about two hours between the three of them.

Completely spent, he sat down in a rocking chair on the back porch of the house while Rachel was inside taking a shower. He’d grabbed a quick shower in the barn after the chores were done, then found a beer in Rachel’s refrigerator.

Dermot took a long drink and closed his eyes. He’d known her for less than a day and she was already the most amazing woman he’d ever met. The work it took to keep the farm running seemed overwhelming and yet she never once complained.

“You put in a good day of work.”

He opened his eyes to find Eddie watching him from the bottom of the steps, Benny standing at his side. “Thanks,” Dermot said, leaning forward in the chair. “And thanks for showing me the ropes. I appreciate it.”

The old man nodded curtly. “Tell Rachel I’m heading into town for dinner. They got bingo at the fire-house tonight and I got some money burning a hole in my pocket.”

“You’re not having dinner with us?”

Eddie shook his head. “I expect you can manage to eat on your own.” He nodded, then put his battered John Deere cap on his head and walked toward the truck, Benny at his heels. A moment later, Eddie and the goat drove out of the yard, leaving a cloud of dust in their wake.

“I didn’t know that goats played bingo,” Dermot murmured.

He stood and stretched, then walked into the kitchen. The least he could do was help Rachel with dinner. He opened the fridge and began to pick through the contents. A salad would be a good start. She’d pulled three steaks from the fridge and they were sitting on the counter near the sink.

“Potatoes,” he said. He found some in a mesh bag beneath the sink. By the time Rachel wandered back into the kitchen, the salad was made, the potatoes were washed and the oven was heating, and he’d poured her a glass of wine.

He handed her the wine, taking in the sight of her. Her hair was still wet, long and loose and curling around her face. She wore a cotton dress, cut deep at the neck. Her feet were bare and she smelled of soap.

“Thanks,” she said, glancing at the table. “You’ve been busy.”

“I’ve decided to make myself invaluable. I am a pretty good cook when it comes to meat and potatoes.”

“I’m glad to hear that. There are nights that I’m just too exhausted to cook and this is one of them.” Rachel crossed to the fridge then pulled out a package of cheese and found a bag of crackers. “This is some of the cheese made from our goats’ milk,” she said, arranging the cheese and crackers on a plate.

They headed back out onto the porch and sat down together in the porch swing. “This is my favorite time of the day,” she said. “After everything is done and the sun is going down and it’s so quiet that you wonder if anyone is still alive in the world.”

“I live on the water in Seattle, so it’s never completely quiet.”

“Do you have a beach house?”

Dermot shook his head. “A houseboat. It’s not actually a boat because you can’t take it out on the water. Although my family has a boat. Actually we have three. We build boats.”

“That’s what you do?”

“I don’t build them myself. I sell them.”

“Motorboats?”

“No. Luxury sailing yachts.”

She frowned. “Why are you here?”

“Because my grandfather decided that my brothers and I weren’t given a chance to follow our dreams when we were kids. He gave us a hundred dollars, a credit card and a bus ticket and I ended up here. I’m supposed to live a different life for six weeks and then figure out if I like it better than my old life.”

“If you have a credit card, why do you need to work?”

“Because he canceled the credit cards once we all got on the bus. I think he wanted us to work rather than lounge around for six weeks. When I landed in Mapleton, I had exactly six cents to my name. I was lucky to meet you.”

“I think I’m the lucky one,” she said with a smile.

They stared out at the sunset, watching as it turned pink and then orange and then purple. “Do you ever get lonely out here?” Dermot asked.

“All the time,” she said. “But I’ve kind of gotten used to it. I just can’t let this place go yet.”

“Why?” he said.

“Because it’s all I have left of my parents,” she said. “It was always the three of us. I’d help my dad with the chores and we’d raise and show our goats at the county fair. And I’d help my mom in the kitchen. She taught me how to bake and sew and keep house. We shopped for antiques and collected quilts. This is who I am, this place. It’s my home and it will be my home until I’m ready to let it go. Does that make sense?”