По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

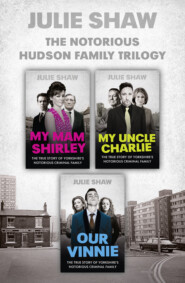

Blood Line: Sometimes Tragedy Is in Your Blood

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Shut your cakehole, Agnes,’ she said now, anxious to get her own jibe in. ‘If your old man had a job, maybe he wouldn’t have the time to spend on women’s work. You only come out to the step so you can do your gossiping. It doesn’t even need cleaning. Stan only painted it again last week.’

‘Oh, my old man should get a job, should he?’ Agnes huffed, standing up now the better to waggle a finger in Annie’s direction. She was fond of doing that. Assuming the ten or so years that separated them gave her permission to carry on like she was Annie’s mother. ‘I’ll have you know, girl,’ she added, ‘that he has a chance of a great job. The railways are setting on and he’s been told he’s in with a chance. Now, that’s a job,’ she said, pausing to let the emphasis sink in. ‘Hmm, let me see … What is it your man does now? Oh yes, that’s right. He waits on up at the Punch Bowl, doesn’t he? When he’s not up there blind drunk, that is.’

Annie flinched as the pain left her back and gripped her abdomen. Gripped it hard, like a fist. Like a vice. Oh, how she wanted to fly for the old witch next door, but now definitely wasn’t the time. She was in labour. She knew the signs. And she knew time was short – little Margaret had been so quick she’d fairly fallen out. So instead, she leaned towards her neighbour and gripped the fencing between the houses. ‘Agnes! Go get the midwife, will you?’

Her neighbour’s demeanour changed instantly. ‘Oh, Annie,’ she said, looking anxious now. ‘Is it your time? Is it the baby?’ She dropped the brush and raised her hands to her cheeks. ‘Oh, sweet Jesus, what’ll I do?’

‘Just get the bloody midwife!’ Annie screamed as it hit her very forcefully that the pains were coming quicker now, and that her little one was spark out in her cot indoors, oblivious. ‘Then come straight back here and watch our Margaret for me!’ she added, trying to keep her legs from buckling. ‘Don’t stand there looking gormless, Agnes. Go!’

Agnes seemed to get the message then, abandoning the soap as well as the brush, then running down her path and out onto the estate. Thankfully, the local midwife only lived a few streets away and if there were no other babies being born that day – and fingers crossed there wouldn’t be – Agnes would find her home and ready to be called out.

Feeling reasonably calm now she knew help was on the way, Annie supported herself using the wall, and waited for the latest pain to subside before staggering back into the house. Once there she knew she had to try and think straight. Margaret was still asleep, curled into a comma in the cot Reggie had made for her, and for a moment or two Annie dithered about waking her. It was almost dinner-time though, and she’d soon be needing a feed. And if things started moving quickly, there’d be no chance of giving her one.

Decided, Annie moved towards the cot. She had to nurse her. And quickly, before the next contraction came – she knew only too well that it might be hours before she was fit enough to do it later. Groaning with the effort, she hauled her daughter from the cot, bringing the blankets with her, then settled into the big chair, better to get her breast out from under her pinny. ‘Come on, baby,’ she soothed to the semi-conscious toddler. ‘Shh, there, come on. Time you had your tea.’

Margaret was angry. And so she would be. She’d been disturbed from her slumbers. She kicked and fussed, at first refusing to take the breast. ‘Come on, you little bugger,’ Annie soothed, wincing as Margaret’s teeth clamped round her tender skin. ‘Make the most of it. You’ll be having to share it soon. Either that, or it’ll be down to the wet nurse with you,’ she gently joked. ‘And knowing her, it’ll come out sour!’

Margaret relaxed eventually and started to suckle, but as the pain started building again Annie knew it wouldn’t last – and, sure enough, as Annie writhed beneath her, Margaret snapped her head back angrily. ‘Mammy, no!’ she yelled, smacking Annie’s breast hard and kicking her. ‘Want bread! Want bread!’

‘Hush, Margaret,’ Annie soothed, trying to keep her voice from rising. The pain deep within her was becoming unbearable. If she didn’t coax her daughter down now, she’d end up falling off anyway. It was just so hard to sit, when she felt compelled to bear down. It was coming. There was no doubt. It was coming.

‘Down you get,’ she said, gently urging Margaret to climb off of her. ‘Baby’s coming now. Remember Mammy’s baby in her tummy? Baby’s coming now –’

‘Baby?’ Margaret’s glass-blue eyes widened. ‘Baby, baby, baby!’

She shuffled down now, energised, and ran towards the cold hearth. ‘Baby!’ she squealed, picking up a stray piece of coal, scribbling on lino with it as Annie convulsed in pain again.

She needed to be down there with her daughter, Annie realised. There was no point in even thinking about her bed now. She needed to be down on the floor where Margaret was. And quickly.

This wasn’t the way I’d planned it! she thought irritably, lifting her skirt.

Agnes and the midwife rushed into the living room together, just at the point when Charles Hudson made his entrance. He slithered out, huge and glistening – a ten pounder, it turned out – and with a pair of lungs any town crier would have been proud of.

‘Oh! It’s a little boy, Annie!’ Agnes cried, her voice breaking. ‘A little gift from God to replace your Frank.’

Agnes had never known Frank. She and Stan had moved into their house in Broomfields a while after he’d died, but Annie knew her neighbour’s emotion was genuine, and felt an unexpected rush of warmth towards her. She felt like crying too, her eyes filling with tears as she held both her babies, wishing above all that Reggie were home to hold his son. She gazed down at the angry pink bundle swaddled close to her chest. He’d be the light of Reggie’s life, she just knew it.

Chapter 3 (#uef994a76-bf06-54a9-9f7c-1395028a6a20)

1932

Charlie was a handsome boy. Everybody said so, especially the women. And he knew it, too. He’d heard it said often enough.

‘Ooh, your Charlie’s gonna be a heartbreaker!’ he’d hear them say to his mam. ‘Ooh, look at those eyes of his!’ they’d coo. ‘Look at that lovely head of hair!’ Then they’d ruffle it and mess it up, which annoyed him.

His hair was black, like his dad’s. His eyes were greeny-blue, like his mam’s. He’d look at himself in the chipped bit of mirror propped above the basin in the scullery, and he’d wonder what it was about his face that was so special. Because it clearly was. The girls in school were always trying to hug and kiss him, and if he rewarded them with a smile they’d squeal in delight.

It was different with the men, and especially with his father, who didn’t seem to trust him. Charlie never understood what it was that his dad disliked about him – was it because he wasn’t Frank? The baby that had come before and died? He didn’t know, but he felt it and it stung. Reggie either completely ignored him – sometimes it was like he didn’t even exist – or he’d pay him rather more attention than made Charlie strictly comfortable, always trying to catch him out doing something wrong, so he could give him a thump or a whack with his leather belt.

‘A sneaky bugger.’ Charlie had heard his dad call him that once. Which had hurt him, because he didn’t even know what he’d done wrong. But it had been all right, because he’d said it to his mam, and she’d given him hell for it. She always did. She was like an animal – his protector, was how he always thought of it. Oh, if she copped his dad giving him the belt for no reason she’d lay into him good and proper, would his mam.

As well as waiting on at the Punch Bowl, which he’d done ever since Charlie could remember, his dad earned a few bob from boxing. He’d do it at the Spicer Street Club, where, unbeknown to the police, they would throw open their back doors and happily host a fight – and between anyone who thought they could throw a punch. It was a nice earner for the landlord, because he’d take bets from the crowd, providing a pot to be shared between him and the winner.

Much as he disliked his father, Charlie loved being taken to watch a fight with him. Boxing was in his blood, and it enthralled him. For as long as he could remember he had watched his dad training in the back yard, punching away at a huge home-made punch bag that was hung from an enormous hook fixed into the house wall. Charlie had even watched his mam make it; it was actually a coal sack that she’d filled with pieces of old lino that had been scraped up, bit by bit, from his grandmother’s kitchen floor.

Charlie trained too. He’d begun when he was three. The linoleum in the sack hurt his knuckles like mad, but he’d soon worked out that it was the one time when his dad would give him his time, so if he’d had his way he’d have punched away all day.

And boxing was the one thing that made his dad proud of him. Never prouder than when he heard Reggie telling his mam, ‘That kid’s gonna be the next Jack Dempsey’.

‘Where’ve you been?’ Annie said now, pulling pins from her hair. ‘You should have been in half an hour back. We’re in a hurry. We’re off to Spicer Street. Your dad’s taking on Billy Brennan today and it’s worth a lot of money.’

It was a Friday afternoon and Charlie was just home from school. He was tired – no matter how long his legs got, the three-mile walk was never less than punishing come a Friday – but this was the best news he’d had all day.

‘I met some mates and we had a kick around,’ he said by way of explanation, lingering for a moment to watch his mam doing her hair. It was black like his and his dad’s but soft where theirs was wiry, and he loved watching her doing it, seeing how she magically made it change, sliding the pins out that she’d put in the night before, in tight little crosses, to reveal curls that would spring out and fall onto her shoulders in big lazy S shapes. He thought she was beautiful and he was glad when people said they could see her in him. She was like a movie star, especially when she put petroleum jelly on her eyebrows. It made her look like that actress Greta Garbo.

‘D’ya think me dad will win, Mam?’ he asked her now.

She grinned. ‘He better do, son,’ she said, pulling her pink cardigan over her shoulders. ‘I’ve got all my mates betting on him. Now go on, go upstairs and get changed, then come back down and wash your face. We have to go.’

Charlie ran upstairs. He’d been the last one home, he knew, but, bar his mam, the house was empty. His big sister Margaret would have taken the rest off to the park, and she’d be giving them their bread and jam after as well. He had lots of brothers and sisters now – they seemed to keep arriving all the time. As well as Margaret, there was young Reggie, who was eight now, and Eunice, who was five, then two-year old Ronnie and little Annie who was still a baby. There was another one coming too, but not till next year, his mam had told him. And he was glad it wasn’t yet, because he didn’t know where they’d fit. His gran always said there was no room to swing a cat in their house, and he agreed. They were all packed in just like sardines.

But this afternoon was his, and as he ran into the bedroom he felt a familiar sense of excited anticipation. When Reggie was nine he’d be allowed to come too, but for the moment, at least, going to the boxing was Charlie’s treat alone.

And as he pulled off his jumper, he also had a brain wave. The week before, he had earned a small fortune – a whole thruppence – for running betting slips around the estate for Mr Cappovanni. Mr Cappovanni was a bookie and his family came from Italy, and Charlie had done work for him for a while now.

Not that he let on quite how much he’d been getting. No, he usually hid it, where it was out of harm’s reach, on this occasion inside a rip in the mattress upstairs. His dad only earned a pound and 12 shillings at the Punch Bowl, so Charlie knew if he knew about it he’d be after getting his hands on it, so he could blow it on beer for him and Annie. So Charlie constantly came up with new places to hide his earnings so he could be sure they’d still be there when he went to find them.

Today, Charlie had a plan for those hard-earned three pennies. He’d use them to place a secret bet with Mr Cappovanni on Billy Brennan. He’d heard about him – heard things that hardly anyone else knew. That, for all his front, Billy Brennan was barely managing to keep his family from starving – so Charlie knew he had an awful lot to fight for. Reggie, on the other hand, was just in it for the booze. His dad was good, yes, but this fight was really no contest, not as far as Charlie was concerned.

He finished changing and turned his attention to retrieving the money. The kids’ bedroom was one of only two in the house, and in this one you probably couldn’t even swing a rat. Not that there was a bed in it; just an old mattress which almost filled the room, set directly on the floor and on which all of the children had to sleep. It stank – of sweat and piss, and other even more revolting things, and was covered in coats, pullovers and scraps of material.

Charlie was lucky, though. He and young Reg, being the oldest boys, at least had an outside edge apiece. Margaret would squeeze up next to Reggie – though she’d often get out and sleep on the floor instead – and all the younger ones ended up in the middle. Here they could piss away all night if they wanted to, because they only got it all over each other.

Charlie held his breath as he glanced at the sunken middle bit of the bed now. Sodden and stinking, it was also crawling with maggots; something he tried hard not to think about at night, but couldn’t escape being reminded of now. He carefully retrieved his savings from the hole in the side and then ran out of the room and back downstairs to scrub his face clean at the kitchen sink.

Annie was waiting in the hallway for him once he was done, and she smiled. ‘Ahh,’ she said, kissing the top of his head, ‘you are a bonnie lad when you’re nice and clean, Charlie Hudson. You, er, wouldn’t happen to have a spare bob or two for your mam, would you, son?’

Charlie smiled back at her, feigning innocence with ease. ‘No, Mam,’ he said. ‘Sorry. Mr Cappovanni lost money this week. I might get summat next week, though, if I work hard.’

He didn’t feel guilty deceiving her. Not on this occasion anyway. His mam would only have used it to bet on his dad, and as far as he was concerned old Reggie boy was going to take a tumble.

Knowing the pennies were in his pocket put a spring in Charlie’s step as he walked with his mam down the street, past the big mill and then across the fields to the club. Cappovanni would definitely be going to the fight, he knew, and that was good because he’d be sure to keep the bet a secret. Billy Brennan was the underdog and when he took his dad down – which he would – Charlie would be in for a tidy profit. Which felt fair, too. He worked very hard for Cappovanni and he knew his employer was proud of him. Proud that he always kept his mouth shut, and also proud that he knew everything about everyone on the large estate where they lived.

The back room of the club was already full of people when he and his mam arrived, thick with smoke, and with a rumble of excitement in the air. It was 5 p.m. now and the fight was due to start soon – it had to be, so it could be all over and done with by the time the club officially opened at seven. He couldn’t see his dad, but knew he was probably limbering up in the toilets – that’s where the fighters went to change into their shorts. He could, however, see Mr Cappovanni. He was moving among the people, looking like any other person, but Charlie, who knew what to look out for in such matters, knew he was discreetly taking bets.

He’d followed his mam to the bar, and now tugged at her sleeve. ‘Mam, is it okay if I go talk to Mr Cappovanni?’ he asked Annie.

She ordered herself a gill of beer before turning to him. ‘Yes, go on then,’ she said, ‘but, Charlie, you be careful, son. That fellow breaks legs to them that owe him. If anything starts, I want you right back with me, you hear?’