По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

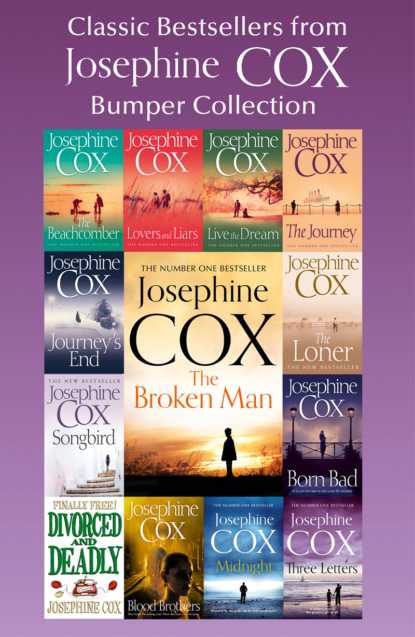

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She laughed at that. ‘Don’t I know it!’ Humouring him, she wagged a finger. ‘By! I’ve yet to see the day when anybody can get one over on you!’

The old man pointed to his half-eaten biscuit. ‘I don’t suppose there’s another one o’ them going, is there? Or mebbe even a couple?’

Prompted by an impulse of affection, she kissed the top of his head. ‘Oh, I dare say there might be a couple more hiding in the larder.’

He gave her a little push. ‘Go on then!’ He grinned, a wide, uplifting grin that showed his surprisingly even teeth, of which he was very proud. ‘A poor old man could starve afore he got any attention round ’ere.’

‘Give over!’ She feigned shock. ‘You get more attention than anybody and well you know it, you old devil.’

‘Mebbe. But it’s another biscuit I’m wanting … that’s if you’ve a mind to fetch me one?’

Straightening up, she sighed, ‘If it’s a biscuit you’re wanting, then it’s a biscuit you’ll get.’ With that she marched off, only to pause at the door and look back on him.

Her heart was full to overflowing as she took stock of that dear old man, his head bent as he lost himself in private thoughts of days gone by. She and her father-in-law had a special kind of relationship, and she was grateful to have him in her life.

Thomas Isaac had no idea she was taking stock of him. He was thinking of his home and his life, and his heart was warmed. Once a big strong farmhand, he had worked his way up, and put money by, until one proud day, he could buy his own little farm. Potts End wasn’t big by anyone else’s standards, but it had been his, lock, stock and barrel, until he had signed it over to Michael and Aggie, and he had good reason to be proud of his achievement. Nowadays, he was too old and tired to pick up a spade, but there were other consolations in life, such as the smell of dew on the morning air, the special excitements of haymaking and harvest, and the sun coming up over the hills. And most of all, the sight of Emily running towards the cottage after one of her long ramblings. Although he missed his wife, Clare, a bonny lass until the consumption took her, he thanked God he had these two wonderful women in his life, Aggie and Emily, for they meant the whole world to him.

He thought back on his youth and smiled inwardly. He’d been a bit of a lad in his day, but had few regrets – except o’ course, it would be good to roll up his sleeves and bend his back to his work, but it wasn’t to be.

From the doorway, Aggie’s thoughts were much the same. She had known Thomas Isaac as a big strong man, and had seen his body become frail and slow. But though his strength was broken, his spirit was not. He still had an eye for the women and a sprightly story to tell. He had a good head of iron-grey hair, and the pale eyes carried a sparkle that could light up a room when he turned on the charm.

Lately though, since all their trials and tribulations, the sparkle had grown dim.

Like her daughter, Aggie cherished the ground the old fella walked on.

‘Are you still there?’ Looking up, he caught her observing him. ‘I’m still waiting on that biscuit.’

‘Coming right up, Dad,’ she promised, and hurried away.

Behind her the old man leaned back in his chair and shook his head. ‘You’ve a lot to answer for, son,’ he murmured. ‘When you took off, you left a pack o’ trouble for these lovely lasses, and no mistake!’

Through the scullery window Aggie saw her brother, Clem, and her heart sank. He was emerging from the outhouse, his huge black dog, Badger, skulking at his side; there was a look of murder on his face, and a shotgun slung over his shoulder. God Almighty, what was he up to now?

She went into the larder and, taking half a dozen biscuits from the tin, she placed them on a saucer and carried them in to the old man. ‘If you want any more, just give me a shout,’ she told him.

Instead of acknowledging the biscuits, Thomas jolted her by declaring in a worried voice, ‘There’s bound to be trouble, mark my words.’

She stooped to answer, her voice low but clear. ‘Why should there be trouble?’

He pointed to the window, where a young man could be seen pacing back and forth. ‘That’s young John Hanley, ain’t it?’

Following his gaze, she too saw John pacing back and forth, growing increasingly agitated. ‘He’s waiting to speak with Clem,’ she informed the old fella. ‘I’ve just been to fetch him.’

‘What does the lad want wi’ that surly bugger?’

She also had been a little curious when John turned up at the doorstep earlier. ‘He wouldn’t say,’ she shrugged. ‘Happen he’s after more work. He’s already finished that job our Michael started him on.’ She gave a cheeky wink. ‘He’s done a grand job an’ all. After eight months o’ breaking his back, he’s made both them wagons as good as new … they’re completely rebuilt from the bottom up, so they are. The hay-trailer is stronger than ever, the ladders are safe to climb since he replaced all the rotting rungs, and he’s repaired so much o’ the fencing.’ She paused, before going on quietly, ‘All the jobs Michael would have done, if only he’d been himself.’

‘Well, young John seems to know what he’s doing.’ The old fella’s feelings were too raw to get caught up in that kind of discussion. ‘The lad may not be the fastest worker in the world but, by God, he’s thorough – I’ll not deny that.’

‘Yes, but all those smaller jobs are finished now,’ Aggie said. ‘And I dare say he’ll be keen to get started on the old barn, just like Michael planned. It’ll be a secure job for him as well.’ She peered out of the window towards the dilapidated barn. ‘By! There has to be at least a year’s work there. Aye, that’s what he’ll be after, right enough … a steady run o’ work right through to next spring.’

‘Look, lass, yer mustn’t forget who’s holding the purse-strings,’ the old fella cautioned. ‘That miserable brother o’ yourn won’t part with a penny more than he has to. I mean, he only paid the lad for all his work ’cause he’d only just got here and wanted to mek a suitable impression.’

Aggie knew that but, ‘It won’t matter either way, if he doesn’t have John back to repair the barn,’ she remarked warily. ‘I imagine the lad can get work wherever he wants.’ She knew he had a good reputation. ‘They say as how he can turn a hand to anything.’

Thomas Isaac looked up. ‘Between you an’ me, lass, I reckon young John is after summat other than work.’

‘What’s on your mind then?’

He frowned. ‘If yer ask me, there’s summat going on,’ he ventured knowingly.

‘Oh? And what might that be then?’

He looked her in the eye. ‘Yer know very well,’ he tutted.

And it was true – she did. These past weeks she had been meaning to speak with Emily about the growing friendship between her and John, only work had got in the way. ‘You’re not to worry,’ she told the old fella. ‘Our Emily’s a sensible lass.’

‘She’s missing her da.’

‘What’s that got to do with it?’ Fear, and a measure of anger rippled through her. ‘We’re all missing him. It doesn’t mean to say we’ll throw caution to the winds.’

‘Emily’s just a lass. She’ll be looking for someone to talk to … someone near her own age.’

‘I know that, Dad, and I’m sure that’s all the two of ’em will be doing – talking to each other. They’re just friends, after all.’

He took a deep breath. ‘Happen!’ That was all he had to say on the matter. But he could think, and what he thought was this: there was trouble brewing. He could feel it in his tired old bones.

Outside, Clem rounded the farmhouse and, coming face to face with the young man, demanded to know his business.

Though needfully respectful, John Hanley was not afraid of this bully. It showed in his confident stance, and in the way he spoke, quietly determined. ‘I came to have a talk with you, sir,’ he replied, ‘if you could spare me a few minutes?’

‘Oh! So you’ve come to ’ave a talk with me, ’ave yer?’ The older man regarded the other with derision, and a certain amount of envy. He saw the lean, strong frame of this capable young man, and he was reminded of his own shortcomings. The eyes, too, seemed to hold a man whether he wanted to look into them or not; deepest blue and fired with confidence, they were mesmerising.

‘It won’t take long, sir.’ While Clem took stock of him, John did the same of the older man.

He had no liking for Clem Jackson. Nor did he respect him, but he owed this bully a certain address, for it was Clem Jackson who appeared to have taken charge of things round here, including Emily. And it was Emily he had come about this morning.

Stamping his two feet, the older man impatiently shifted himself. ‘Get on with it then, damn yer!’ he instructed roughly. ‘Spit it out! I’m a busy man. I’ve no time to wait on such as you!’

Taking a deep breath, John said, ‘I’ve come to ask if you will allow me and Emily to walk out together?’

‘Yer what!’ Growing redder in the face, Clem screamed at him, ‘Yer devious little bastard! You’d best get from my front door, afore I blow you to bloody Kingdom Come!’ Beside him, Badger’s hackles were raised, and he growled low in his throat.

Raising the shotgun, Clem aimed it at John’s throat, his one eye trained down the barrel and his finger trembling on the trigger. ‘I’ll count to ten, and if yer not well away by then, yer’ll not be leaving on yer own two feet, I can promise yer that!’

With his heart beating fifteen to the dozen, John stood his ground. ‘We’re just friends, sir,’ he said quietly. ‘There’s nothing untoward between us. Only, I am very fond of her, and I know she’s fond of me, because she’s said so. But it’s all right and proper, sir. I respect Emily too much to harm her in any way.’

At any minute, this madman might pull the trigger, or that hound might fly at his throat, but John felt compelled to say his piece. He and Emily had these strong feelings: in truth, they were growing to love each other in a way that only a man and woman could love. Now, it was time to put it all on a proper footing.