По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

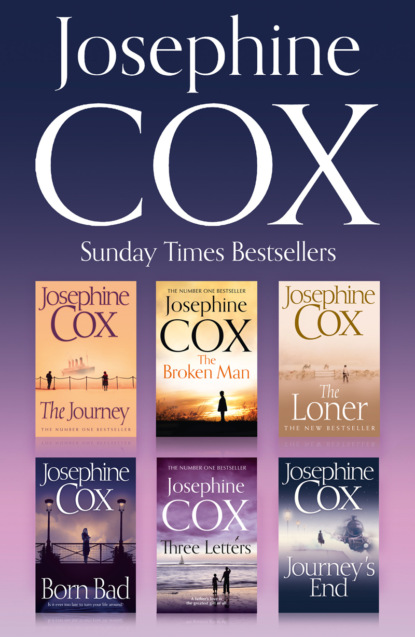

Josephine Cox Sunday Times Bestsellers Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Ah, you’re just saying that.’ Ronnie searched the table for another chunk of fruit-cake. ‘I bet you’re really in agony from the number of times he’s trodden on your toes.’

At half past midnight the evening came to an end.

As they left, everyone said what a wonderful time they’d had, and how good the food was, and how they would be so sorry to see the Davidson family leaving.

Standing side-by-side at the door as they saw everyone out, Barney and Vicky thanked them all in turn.

‘I’ll see youse out and about before you sail away, so I will!’ Having downed more booze than she was capable of holding, Bridget was four sheets to the wind. ‘Oops!’ Laughing raucously, she hobbled out to the waiting car, clutching hold of her companion, her jacket stained with wine and her hitherto beautifully coiffured hair looking as if it had been through a wind-tunnel.

Behind her, Barney and Vicky walked arm-in-arm back to the house with Lucy and Susie, who had danced with her friends until her feet ached.

‘Leave all that till the morrow,’ Barney told his sons, who had a mind to start clearing away the furniture. As it was, he left them sitting on the barn floor, finishing off their drink and deep in conversation. ‘D’you think they’re worried about going to America?’ Barney asked Vicky.

‘Not a bit of it!’ she declared. ‘They’re very excited, like the rest of us. In fact, Thomas said he would be brokenhearted if Leonard Maitland suddenly changed his mind and said we couldn’t go after all.’

Her words did not help Barney. Instead he felt as though his own heart might break, because very soon he would have no choice but to confess the truth of his illness. And the more he thought of it, the more he dreaded the day.

Inside the house, they found old Meg fast asleep in her chair, with the knitting on her lap and snoring like a good ’un. Barney chuckled. ‘We’ll have to wake her,’ he said. ‘The old dear needs her bed.’

Vicky gently shook her, and when she woke it was with a start that frightened them all and sent her knitting clattering to the floor. ‘What’s up? What d’you want?’ With big eyes she stared at them. ‘Oh, it’s you.’ Her mouth opened in a toothless grin. ‘I thought for a minute it was me old man come back to haunt me.’

‘Come on, my old darling, it’s time you were tucked up in bed.’ Barney helped her out of the chair, Vicky went to fetch her hat and coat and Lucy paid her for the night.

Ronnie came rushing in. ‘Your son’s here,’ he told her, and her old face lit from ear to ear. ‘He’s a good lad,’ she said. ‘He does look after his old mammy.’

No sooner had she been helped into the car than she was fast asleep. ‘Salt of the earth,’ her son told Barney with a proud smile. ‘Never stops … allus on the go. She’s in her seventies now, but I reckon I’ll be worn out long afore she is.’

After Meg had gone, Jamie woke up and started crying. Lucy ran upstairs and came down with him in her arms. ‘Oh dear, he’s wet the bed. I am sorry. I’ve put the sheets in the pail to soak and I’ll rinse them through tomorrow. The mattress is still dry – thanks to your old rubber sheet. Look – I think we’d best go home.’

‘If you want to stay I’m sure we’ll find something suitable to wrap his little bottom in,’ Vicky said. ‘And there’s plenty o’ clean sheets – you know where they are.’

Lucy thanked her but thought it might be best if she took Jamie home and saw to him there. ‘It’s been a very long couple of days and he’ll rest easier tucked up in his own cot.’

‘We’ll see you tomorrow then,’ Vicky told her, while Barney went to fetch his big coat.

Ten minutes later, wrapped against the cold night air, she and Barney set off with the child, who by now had nodded off again. ‘I don’t know how to thank you,’ Lucy told Barney.

‘Thank me? What for?’ He hoisted Jamie higher in his arms.

‘For giving Jamie the party.’

‘It was a pleasure,’ Barney answered. ‘And don’t forget, it was also to mark our going to America.’

Something in his tone caused Lucy to ask, ‘And is that what you really want, Barney, to go to America?’

The man chose his words carefully, not least because Lucy had already voiced her concern about his health. ‘O’ course I want to go! Why wouldn’t I?’

Lucy gave him a sideways glance; in the moonlight he looked incredibly pale, and there was a quietness about him that wasn’t natural. Twice during the evening she had seen a kind of sorrow in his face that worried her.

‘What’s wrong with you, Barney?’ she asked quietly. ‘And don’t fob me off with untruths. I’ve come to know you fairly well, and I’ve a feeling there’s something up. What is it? You can trust me – you know that, don’t you?’

Barney didn’t answer, nor did he look at her. Instead he kicked irritably at the roadway. ‘It’s high time somebody did summat about these damned ruts in the lane,’ he grumbled. ‘Last week, old Ted Foggarty’s horse caught its fetlock in one and had to be put down!’

Lucy persisted. ‘Talk to me, Barney.’

‘I am talking.’ He gave her a cursory glance.

‘I haven’t said anything to Vicky and I won’t, but I know there’s something wrong,’ Lucy repeated. ‘Bridget told me she saw you going into the doctor’s surgery some time back.’

Turning to look at her, he said, ‘I won’t hear any more of this nonsense, Lucy. Yes, I won’t deny I went to see the doctor, but only because I was feeling run down. I’ve been under the weather recently and I thought it might be a good idea to go and get some tonic.’

‘And did he prescribe some?’ Lucy was slightly relieved but still left with the feeling that he was not telling all.

‘He did, and I’ve been taking it religiously.’

‘And is it working?’

Barney was feeling trapped. ‘Well, you’ve not seen me being other than fine, have you?’

Lucy shook her head. ‘No.’ Enough was enough. Barney was getting grouchy. ‘But I’m not always looking in your direction, am I?’

Barney laughed it off. ‘I should hope not!’

When they reached Lucy’s cottage, he helped her inside with her bag and the child. A few minutes later, he and Lucy emerged from the front door. ‘Good night, Lucy girl,’ Barney said, and yawned long and hard. As always, he kissed her on the cheek. ‘See you the morrow.’

‘Good night, Barney.’ She waved him off down the lane, and afterwards went back inside, her face still burning from the touch of his lips. It was a sad thing, she thought, to love a man who belonged to your best friend. But love him she did, and try as she might, she could not change that.

Neither Barney nor Lucy had seen Edward Trent hiding in the shadows, watching and waiting. When Lucy was kissed good night, he was shaken by the look of love on her face as she waved Barney off. And his heart was black with jealousy.

Having had a run of bad luck of late, he had heard through the grapevine how Lucy had been given a cottage to live in and regular work. With no sailings available and with nowhere to live, Trent had thought to foist himself onto Lucy by persuading her that he loved her and the child. Once he’d got his feet under the table, he’d plan his next move, while Lucy worked to bring in the wages and he worked to spend them.

The thing that shocked him now was that, having come back with purely selfish motives, he had seen Lucy in other men’s arms and realised he still had deep feelings for her. She belonged to him, by God. He’d taken her virginity, and by rights she was his, and the mother of his son – not that he could even remember the brat’s name.

Inside the cottage, Lucy quickly washed the child with a drop of warm water, talking to him as she did so. ‘This is our home, Jamie. It might be small and cramped, but now that Barney’s mended the roof and fitted new doors, and me and Vicky have polished the entire place till it shines, it might not be the poshest place in the world, but it’s cosy enough for me and you.’ In fact she loved its every nook and cranny.

‘It was a good party,’ she said, slipping on his pyjamas. ‘Barney and Vicky gave it just for you.’ She recalled what Barney had said. ‘And it was to say goodbye to their friends as well, because soon they will be off to a new life across the water.’

Pushing the heartache to the back of her mind, she told the child, ‘You’re christened now, sweetheart.’ She kissed his sleepy face. ‘It’s wonderful, isn’t it? You have your name written down in the book for everyone to see.’

When she tickled him he chuckled and squealed, and she took him in her arms, hugging him as if she would never let him go. ‘You’re Mammy’s big boy,’ she said. ‘We’ll soon be losing the best friends we’ve ever had, so we’ll need to look after each other, you and me, eh?’

‘Not when I’m around to take care of you.’

‘EDWARD!’ Even before she turned, Lucy knew the voice, she knew the man, and could hardly believe he was standing right here in her house.

‘You should always lock your door at night.’ His slow, dangerous smile enveloped her. ‘You never know who’s lurking about.’

‘What do you want?’ Instinctively, she held the child closer. When he took a step nearer, Lucy stepped back.