По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

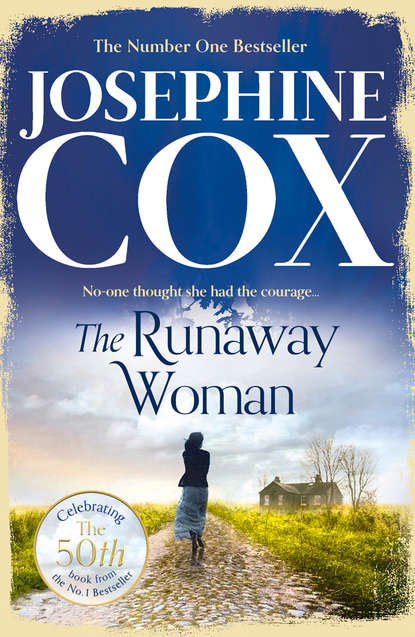

The Runaway Woman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They hardly ever made time to sit and chat with her. Anne and Paula’s visits would be little more than a cup of tea, then a quick peck on the cheek and they’d be off out the door. More often than not, Martin would then go off down the pub. ‘I’ll not be long,’ he’d promise her. But it would be gone midnight when he got home.

Lucy was daunted by the fact that she would soon be forty years old, especially when she considered she had done nothing with her life. She had never seen much outside Wayburn, and as the years went by, the idea of travelling and doing the exciting things she had once dreamed of seemed increasingly out of her reach. She now feared her life would remain as it was until she became old and unable to make changes.

As with all the other birthdays, she wondered if this landmark birthday would arrive quietly and leave on tiptoe, though if it did she knew she would take it in her stride, as ever, while secretly wondering if her family could ever love her as much as she loved them.

There were even times when she asked herself if she was a useless wife, mother and grandmother. She hoped not, because her family was all she had. In fact, they were her very world. Consequently she felt it was wrong of her to ask more of them than they could give.

There was one bright side to Lucy’s life, however. She was immensely grateful for her job at the plastics factory. She took great pride in her work, and enjoyed the company of her lively colleagues. Chatting with them made her feel alive, because to them she was not just someone’s wife, mother or grandmother. Instead, she was Lucy, a well-respected and much-valued workmate.

Deep in thought, Lucy was startled to hear the hallway clock strike five. Careful not to wake Martin, she slithered out of bed and into her dressing gown, then she softly slid the eiderdown over the dip in the bed where she had lain.

Gazing down on her sleeping husband, she tortured herself with regrets. So many wasted years, she thought bitterly. So many lost dreams.

Inevitably, her thoughts returned to their two children. Sam was now twenty-one. Like all young men he could be bullish and unpredictable, but beneath all the bravado, he had a sense of purpose.

At twenty-three, Anne was her first-born. She was confident, easily hassled, and occasionally argumentative. She was the mother of Luke, almost one year old.

The thought of her only grandchild brought a measure of joy to Lucy’s heart. Full of life, he had a ready smile and laughing eyes that made you want to dance, and he was an absolute delight.

Taking a moment to close her eyes, Lucy cast her mind back to when she was a shy, innocent girl, afraid of everyone and everything; until Martin made friends with her in the school grounds one sunny afternoon.

With his smiling brown eyes and wild shock of thick, dark hair, he stood out from the crowd. Tall and lean, with an attractive, lazy way of walking, he was a magnet to the opposite sex. After that first meeting, Lucy was instantly drawn to him, though never in a million years did she imagine how their lives would intertwine. It would have been impossible to believe that less than two years after their first date she would not only be Martin’s wife, but she would also be mother to his child.

Over the years, Lucy had often wondered about that fateful night, when curiosity, excitement and a sense of belonging took away their common sense. The consequence of that had carried them to this point in their lives, and Lucy had come to realise how wrong they had been to get married, especially when they were both so young, with little knowledge of real life and responsibility. The sad truth was, that she had never been truly happy; not on the day they got married, and certainly not now.

For a long time, she had desperately wanted to find a way out of this mundane life, but her strong sense of duty gave her no easy way out.

Now, she often looked down on Martin’s sleeping face, and thought that, yes, she did love him; if loving him was to take care of him, to feed him, wash and iron his clothes and do her best to make sure he was content.

She went to gaze out the window. I do love you, Martin, she thought, but I don’t know you … at least not in the way I should.

She resented the way he had always made the important decisions without consulting her. Also, she resented the cowardly way she had allowed herself to go along with his decisions. When they were still at school and she found herself pregnant, it was Martin who had decided that keeping it a secret was the best thing to do. Also, it was he who’d insisted they should get married as soon as possible so that no one would find out right away. But they had been wrong, Lucy now knew. They should have confided in someone older and wiser, whom they could trust. Someone who might have helped them.

Choking back the anger, she became tearful. I should never have listened to you, she thought. I wanted to tell them the truth, but you wouldn’t let me. She recalled vividly how he threatened to say the baby wasn’t his.

Though when Mum guessed I was pregnant, you did stand by me. Even so, on my sixteenth birthday, when we were getting married, I was so afraid that you would get scared and run off at the last minute and I would have to face it all on my own.

Her homely features creased in a smile. You didn’t run though, did you? She turned, crept back and kissed him softly on the cheek. ‘Now though, I can’t understand what’s happened to us, Martin,’ she whispered. ‘I’m not happy, and sometimes I believe you feel the same.’

When a tear escaped down her cheek, she angrily wiped it away. It was no good crying. What was done was done, and there seemed no turning back.

She continued to observe him a moment longer, hating herself for being cowardly back then when they were unsure and afraid. How could she ever forget the shame and the trauma when they told their families that she was expecting a child, when she was little more than a child herself?

On the whole, over the years, Martin had been a good man. Right from when their daughter was born, he had proved himself to be a good husband and a fine father – although if she were honest there had been times when she might have preferred him to spend more time at home with her and the baby.

That particular problem still niggled her, especially when he chose to share all his leisure time with his mates, rather than with her. She was at home every evening – at first with the babies, and now alone.

Lucy’s insecurities had never really gone away.

What if he had never loved her at all? What if he had only married her because she was having his child? Maybe, unknown to her, he also had regret and doubts about the traumatic decision they had made back then. Yes! Maybe he felt like she did: cheated and alone, in a marriage born out of panic.

As a child, Lucy had always dreamed that her wedding day would be a magical, proud occasion. Instead, on her sixteenth birthday, it was a frantic rush, and all because of one dark and unforgettable night behind the Roxy.

Just two years after their daughter Anne was born, Lucy and Martin were blessed with the arrival of their second child – a boy who they named Samuel. Sam. Martin then decided that two children were enough, and took precautions to make sure their family never grew any larger.

Lucy, over the years, had devoted her life to her family. Martin played his part well, but preferred to be fishing, playing darts down the pub or kicking a ball about on the green with his friends.

After Anne married, and with Sam increasingly leading his own life, Lucy was mostly left on her own.

Inevitably, the distance between her and Martin began to widen. One time he came home so drunk he could hardly stand. ‘A mate of a mate was out on his stag do,’ he lied, ‘so we decided to make a night of it.’ Lucy made no comment, but from the whiff of cheap perfume she suspected he may have been enjoying female company.

After the second drunken episode, he gave no explanation, and Lucy asked for none. Consequently, the gulf between them became a chasm, with Lucy feeling increasingly isolated.

She had learned to take the good with the bad, but lately she had grown increasingly restless. One way or another things would have to change. She had no idea how or when, yet change they must, because if they continued as they were now, she would likely spend the rest of her life regretting it. Now, heading towards her fortieth birthday, she assumed that half her life was already gone; did she really want to spend her latter years wishing she had found the courage to put herself first, especially now, with the children grown up?

With that thought burning in her mind, she made her way downstairs. Usually after a bad night there was no spring in her step, but today was different. Never before had she felt so defiant.

If she truly wanted it, she believed that she could make a change. She could rebel. She could do something outrageous – something she had never done before.

But then the doubts crept back. Where would she start? What would the family say if she was to do something out of the ordinary? As Martin had once remarked, ‘You could set your clock by our Lucy. Always on time, and everything in its place, that’s her.’ The idea of timid Lucy Lovejoy actually rebelling was unbelievable.

But then the more Lucy thought about it, the more excited she became. So what if she was coming up to her fortieth birthday – surely it wasn’t too late to step out of her routine? To do something so brave and wonderful that she would remember it for ever? What was so wicked about that?

Her imagination ran riot. Twirling round the kitchen, she listed her unlikely ambitions aloud in a singsong way: ‘I could go dancing till dawn, or run full pelt along the promenade, in nothing but a tiny swimsuit and flimsy throw-on. Oh, and I might even book myself onto a big cruise ship … and sail off to exotic places.’

But then suddenly her mood changed as she sat down at the table. Who am I fooling? she asked herself. I’ve got no money to speak of, and anyway it’s too late now. It’s such a pity, though, because there are so many exciting things I’ve never done. I’ve never been to London, or a theatre, and though I’ve always wanted to, I’ve never learned to roller-skate … The sorry list of lost opportunities was endless. She had never worn a short, swingy skirt, or had a ride at a fairground. Never even learned to swim. In fact, she had never done anything exciting or daring. ‘You’re a hopeless case, Lucy Lovejoy!’ she declared.

Instead, she had become a watcher. Watching the children play in the sand. Watching everyone else enjoying themselves while she minded the bags or the pram, or kept the towels dry while they were swimming at the local indoor pool. She had always been a shadow in the background. Hardly noticeable, always in demand to smooth the way for the family. In the end, there was never any time for her.

She never complained, so it didn’t cross anyone’s mind that she might want to live a little, to join in the fun while someone else watched the bags and the pram.

Lucy cast her mind back. She was sure there must have been times when the family did ask her to join in but, for whatever reason, she never did.

As always, blaming herself was easier than blaming them.

Aware of the clock ticking away on the wall, she began to set the table for breakfast. Silly old fool! she told herself. You’re a hopeless daydreamer. Always have been. Put it all out of your mind and get on with the life you have. To have an adventure you need youth on your side, you need money, and you definitely need a plan. You have none of those. At your age a new adventure is just a pipe-dream.

Even so, the idea of a new life lingered.

As she set about cooking breakfast, she couldn’t help but wonder what the neighbours would say if they found out that Lucy Lovejoy had done a runner.

She burst out laughing. It might be worth the adventure, just to see the look on their faces!

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_ef1aaa78-f8ed-54ba-8195-701f279a5cd1)

THE EGGS AND bacon were all nicely sizzling in the frying pan when Martin rushed into the kitchen. ‘For goodness’ sake, Lucy, I told you last night I wouldn’t have time for any breakfast this morning. What’s the matter with you? You even forgot to set the alarm clock for six. Thanks to you, I’m in a rush now.’

‘I can’t remember you asking me to set the alarm earlier, and anyway, if you were that worried about being late, why didn’t you set it yourself?’