По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

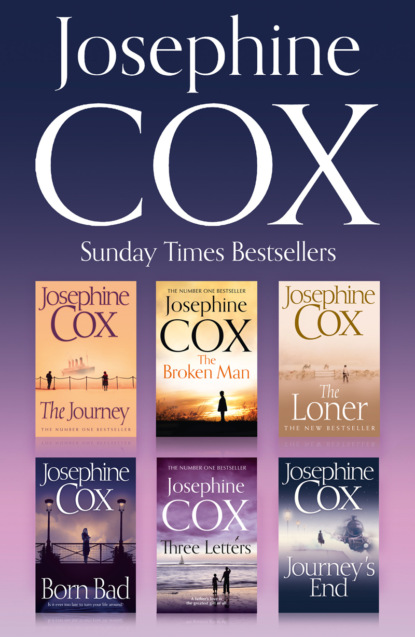

Josephine Cox Sunday Times Bestsellers Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was many years later when, looking back on that magical, intimate moment, with the child asleep and the two of them gently following the narrow country lanes, Barney contentedly smoking his pipe and the sound of the birds singing all around, Lucy realised she must have fallen hopelessly in love with him then – and she never even knew it.

Barney Davidson. A wise and kindly man who knew the earth as if it was his own; a man who had the heart of a lion and could protect the weak, that was Barney.

Just for now though, misinterpreting her deeper feelings, Lucy saw Barney only as a very dear friend. No more than that.

Yet, even though many a moon would shine before she came to realise the true depth of her feelings for him, Lucy already knew in her heart and soul, that she would never meet his like again.

Chapter 9 (#ulink_c3a4409c-cfe2-5dca-9014-f2f18583cb81)

THE WEEKS PASSED and already it was the end of July.

Lucy and Jamie had settled in well to Mr Maitland’s vacant cottage. It was almost as though they had lived there forever. Lucy was happier than she had ever been; every day was like a holiday. Her life was filled with new experiences and here in the countryside where she was a part of the greater picture, what had previously seemed to her like mountainous problems, now seemed almost trivial.

She counted herself fortunate to have such friends as the Davidsons; they were a joy to be with. Working or relaxing, every minute in their company drew her more and more into their family.

Sometimes on a Sunday evening, Bridget or one of the girls from Viaduct Street would visit, and they would sit and talk, and laugh to their hearts’ content. Lucy made sure to keep a measure of the ‘good stuff’ hidden away for when Bridget came. ‘Oh, you’re a darling – what are ye?’ Tipping up her glass and warming the cockles of her heart, Bridget would dance and sing and go home all the merrier.

As arranged, through the week Lucy worked with the Davidsons, and on Saturday morning she went up to Leonard Maitland’s house, where she did the ironing and other jobs like cleaning his silver. After midday her work was done and the weekend was her own, to enjoy the cottage and play with her child.

Each day saw Jamie grow more and more sturdy; he now was very active and the fresh air was doing him a power of good. He loved his new family and had begun to talk in his own way to them all. Everyone loved the little toddler and enjoyed having him around the farm.

On this particular Saturday, Lucy was replacing the silver in the display cabinet, just about to finish her morning’s work, when she heard voices in the next room. ‘Sometimes I’m not sure I’m cut out to be a farmer’s wife.’

‘Hmh! I wish you’d told me that before I put an engagement ring on your finger.’

There followed a girlish peal of false laughter and the light-hearted suggestion, ‘Oh, Lenny! Why don’t you sell everything – this house, the land and cottages. We could move down to London – or go abroad! It would be so wonderful to travel. We could stay away for a whole year … see the world, do something exciting.’

There was a brief silence, then the woman demanded, ‘Are you deliberately ignoring me?’ Another silence, then in sterner voice: ‘Leonard! Did you hear what I said?’

‘I heard, and yes, I am deliberately ignoring you, Pat. We’ve had this same conversation so many times I’m beginning to tire of it.’

Only the thinness of a wall away, Lucy recognised the voices of Patricia Carstairs and Leonard Maitland. She tried hard not to listen and even softly sang to herself, but the voices grew louder and angrier, and she couldn’t help but overhear every single word.

‘Yes, and so am I tired of it!’ Anger trembled in her voice. ‘Whenever I take the trouble to drive over and see you, you’ve either got your head buried in paperwork, or you’re out with your man discussing tractors or some such thing, or overseeing a delivery. Yesterday, and not for the first time, I came here to find you ensconced in your office with two other men, and even when you knew I was here, you just popped your head round the door and excused yourself. My God, Leonard! You didn’t come out for a full hour, and I was made to hang around like a dog at its master’s heels. These days, you hardly ever have time for me, and that is not how it should be. I should come first in your life and I don’t. And I’m really fed up!’

‘Then listen to what I’m saying.’ Leonard sounded weary. He was weary – of her demands, of her chastising, and of her misguided belief that he, like her, had nothing better to do than socialise. ‘I’m a farmer, Patricia … a busy man. You knew that when we met and you know it now. I can’t change that. I won’t change it.’

‘But you don’t actually farm, do you?’ Her tone was cynical.

Leonard gave a dry, angry laugh. ‘You just don’t understand, do you?’ he said. ‘I may not often sit in the tractor, or plough in the seeds, or cut the corn when it’s grown. But I’m a landowner and as such have certain responsibilities. I plan which seeds go into the ground, or which tractor suits the job best. I scour the country for the best price I might get for my harvest … There are a multitude of things that come with working the land. I monitor every single thing. I buy and sell, and treat my part of the job with respect.’

‘But you have Barney Davidson. You sing his praises so often, I’m sure if you let him, he would take a lot more responsibility from your shoulders.’

There was another moment of silence; a moment when Lucy felt uncomfortable, for she could almost taste the atmosphere.

It seemed an age before, in a cutting voice, Leonard Maitland spoke again. ‘You will never understand, will you, Patricia? You don’t even try to understand the implications of what I’m telling you. I bought this land because I needed to. If I didn’t have land around me, I would simply suffocate. But land is not just for looking at, and when you take it on, you give yourself wholeheartedly to its well-being. You treat it like a living, breathing entity, because that’s what it is. The land gives more than it takes, and it deserves to be cared for. But, like I say, you will never comprehend that, and I don’t blame you for it.’

‘I’m sorry, Lenny darling.’ True or false, the voice and its owner seemed contrite. ‘All I’m saying is, why not let Barney take over occasionally? After all, you’ve always said he knows the land as well as you do. I can’t count the number of times you’ve remarked on how a capable man like Barney Davidson was meant to have his own farm, but that life had not treated him kindly enough.’

‘Yes, Pat, and I meant it. But this is my land. My responsibility. Barney is my partner in a sense. He is my eyes and ears, and while I organise everything else, he farms, and that’s all right, because he has the same love for the land that I do.’

‘Oh Lenny.’ The voice grew whining. ‘I know how passionate you are about this place …’

‘No, you don’t.’ Now he was calmer, wanting to explain. ‘You live in town. You can have no idea of what it feels like to see the harvest being brought in, or to stride the fields on a winter’s morning, when the snow lies deep in the ditches and the trees bend and dip with the weight.’ His voice dropped. ‘If you want us to marry, as I do, then you must accept that my work is important to me.’

‘All right, my darling, but why can’t we go away – for a month maybe?’

‘We will,’ he consoled her. ‘Look, we’re due to be married next spring, and if it suits you, we can have a much longer honeymoon than planned. How’s that?’

‘And can I plan where we go?’ She was a spoiled child.

‘If you like, yes.’

‘And money’s no object?’

He gave a sigh. Did his fiancée not realise that most of the world was plunged into a financial crisis? ‘It is our honeymoon after all,’ he said resignedly.

‘Oh, Lenny, it will be so wonderful!’ Excitement coloured her voice. ‘Then in the winter, can we go far away – to the South of France or even further afield? My London friends spent last winter in Sydney and they said it was the best time they ever had. Oh, it would be so nice to get right away. I do get so bored visiting the same old places.’

‘You’re a mystery to me.’ A different emotion crept into his words. ‘You’re infuriating and selfish, and sometimes I wonder what I see in you. But fool that I am, I can’t help but love you.’

‘I’ll remember that when you refuse me what I ask.’

‘You will have to remember something else too.’

‘For instance?’

‘For instance, that being a landowner, I must bow to my duties here. There will always be times when I can’t just take off at your every whim and fancy.’

There came that soft trill of laughter again. ‘We shall have to see, won’t we? Now I think you should give me a kiss, by way of apology.’

‘Don’t you think the apology should come from you?’

‘Aw, Leonard! Does it really matter who apologises? Kiss me, and we’ll forget we ever quarrelled.’

Silence reigned for a moment, when Lucy imagined they were in the throes of the ‘apology’. Then came the sound of a door opening and closing, and when she glanced out of the window, Lucy saw them going arm-in-arm down the driveway to the long black car, recently chosen by Patricia Carstairs, paid for by Mr Maitland, and delivered only three days ago.

‘Oh darling! Won’t people be envious when they see us together in this!’ was Patricia’s parting remark as she climbed into the car.

Lucy watched them drive off; the woman slim, beautiful, and arrogant to the quick, while the gentleman was attentive and homely, a gentle giant of a man.

Lucy thought them quite unsuited. ‘That one’s trouble. He should drop her like a hot potato!’ Closing the curtains, she pranced across the room on tippy-toe, emulating Patricia Carstairs, one hand on her hip, the other swanking by her side, mimicking the woman’s voice to perfection. ‘Oh darling! Won’t people be envious when they see us together in this?’ She pitied the poor wretches who had no work and no money; to see a smart car passing by, occupied by that one with her nose in the air would be like a red rag to a bull.

Breaking into song, Lucy returned to her work, gave the large silver teapot another rub with the cloth, then with the greatest of care replaced it in the cabinet, where she shifted the silverware about until the display was pleasing to the eye.

She now closed the door, took up a clean cloth from her basket and giving the door-glass a good polish, gave a sigh of relief. ‘All done for another week!’

A few minutes later, she was out of the house and running across the back lawns towards the fields. Now, as she rounded the brow of the hill, she heard the laughter from Barney’s house. Pausing, she took off her shoes, set off at the run and before long was at the gate of Overhill farmhouse. ‘Quick, Lucy!’ Vicky was beckoning her. ‘Hurry!’