По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

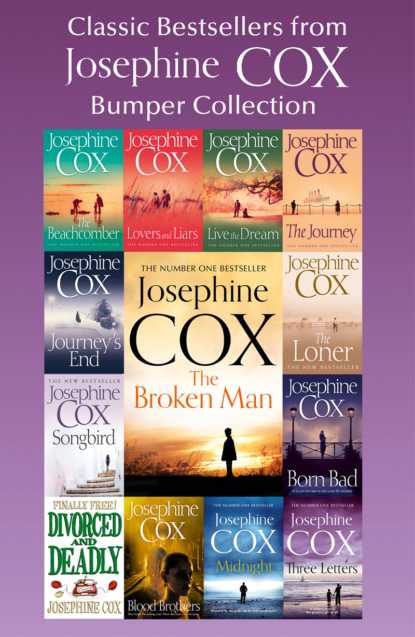

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Luke’s distribution business prospered, though its downside was that whenever one of his customers took a wrong turn and went under, Luke lost a sizeable slice of his business’s turnover. This had happened a few times, and on each occasion it threatened a serious step back.

This was what his employees now feared: that there had been others who had taken that ‘wrong turn’ and now it was themselves who were about to lose their livelihoods.

And so this morning, when they would learn their fate, they gathered from all parts of the factory: from the brush-making side, where the machines clattered all day and both men and women worked them with expertise, some cutting out the wooden shapes that would make the brush-tops, some feeding the bristles into the holes that were ready drilled and cleaned, and others fashioning and painting the handles.

When the production line produced the finished articles, the packers would neatly set them into boxes and the boxes would be carted away for delivery.

By nature, this was a dusty, untidy area, with the smell of dry horsehair assailing the nostrils, and the fall of bristles mounting high round the workers’ feet. Yet they loved their work and many a time the sound of song would fill the air.

The other side of the premises was cleaner, with mountainous stacks of boxes and parcels from other factories as well as Hammonds, all labelled and ready for delivery, and the four wagons in a neat row outside waiting to be loaded.

For the past few days, however, there had been only two wagons waiting, with the other two stationary further up the yard. Rumours had circulated, unease had settled in, and now, the mood of worried workers was so palpable, it settled over the factory like a suffocating blanket.

From his office at the top of the factory, Luke watched the workforce gather in the front yard. ‘They’re in a sombre mood,’ he told the clerk.

‘Aye, they are that, Mr Hammond.’ A ruddy-faced Irishman with tiny spectacles and tufts of hair sprouting from his balding head, old Thomas kept his nose glued to his accounts book.

Luke had some fifty people in his employ, and seeing them gathering in one place like now, it made a daunting sight, which filled him with pride and a sense of achievement, and also with apprehension. ‘They’re a good lot,’ he told the clerk.

‘Aye, they are that, Mr Hammond.’ Licking his pencil Thomas made another entry in his ledger.

Luke turned from the window to address him. ‘I expect they’ll be wondering why I’ve called them together like this.’

This time, Thomas glanced up. ‘Aye, they will that, Mr Hammond.’ The old man had been with Luke’s father before him, and was a loyal, trustworthy man who knew everything there was to know about the Hammond business.

Looking away, Luke smiled. ‘You’re a man of few words, Thomas.’

Thomas gave a long-drawn-out sigh. ‘Aye, I am that, Mr Hammond.’ Now as he glanced up, he smiled a wrinkly smile. ‘A man o’ few words, that’s me, so it is.’

Realising all the workforce were now gathered and waiting, Luke straightened his tie and fastened the buttons on his jacket. ‘It’s time,’ he said, opening the door. ‘I’d best tell them why they’re here.’

Downstairs, the atmosphere was one of apprehension. There were those who expected to be finished on the day, and others who prayed they might be allowed another few years of work and pay before they were put out to pasture.

‘Ssh! Here he comes!’ The word went round, a hush came down, and, hearts in mouths, they watched Luke’s progress as he came down the staircase.

‘If I’m for the chop, I’ll sweep the streets rather than be cooped up in the shop, a grand little place though it is.’ Being a man with an appetite for fresh air, Dave Atkinson was adamant he would find outdoor work.

‘I’m sixty-two year old,’ said another man. ‘Who in their right mind will tek me on at my time o’ life?’

‘Ssh!’ The ruddy-faced man in front turned round. ‘He’s here now.’

When the muttering was ended and the workers’ attention was on him, Luke revealed the reason for their being there. ‘Firstly, I want to thank every one of you for your loyal service and dedication to this company …’

‘Bloody hell!’ Half-turning to Dave, the ruddy-faced driver whispered, ‘That sounds a bit final, if you ask me.’

‘Ssh.’ Dave gestured towards Luke. ‘We’d best listen to what he has to say.’

Luke went on: about how proud he was of them all, and how, ‘I would have told you before but I had to wait and be sure.’

Recalling the endless meetings and frustrations of the past weeks, he took a moment to formulate his words. ‘I’ve had to do some hard talking these past few weeks and I don’t mind admitting there were times when I despaired. But I got there in the end, and now I can tell you that the future looks good, and we’re about to expand. The premises will be doubled in size and the fleet increased to eight wagons – the old ones going two at a time, until we have all eight exchanged for brand-new ones.’

With the workforce’s full attention, he continued, ‘All this will take time but, as you can see, two of the wagons have already been set aside for a ready buyer. I’ve secured two long-term contracts with sizeable companies based in Birmingham, and the hope of another in the pipeline.’

For a long, breathless minute, the silence was deafening.

Clenching his fist, Luke punched the air. ‘That’s it, folks! GO TO IT!’

He may have said more, but his voice was suddenly deafened by the biggest cheer ever to have been heard in that yard.

‘GOD BLESS YER, SON!’ Like many others, delighted and relieved, the ruddy-faced driver was leaping in the air, fists clenched and tears swimming in his eyes. ‘We all thought we were for the bloody chop!’

Tears turned to laughter, and Luke went amongst them, with congratulations coming from all sides. He was deeply moved by the loyalty of these ordinary, wonderful people.

‘Back to work now,’ he told them, and with smiles and much chatter they ambled away and, well satisfied with his own considerable achievements, Luke returned to the office.

‘These good people have made this business what it is today,’ he told the old Irishman.

‘Aye, they have that, Mr Hammond.’ Thomas wondered what Luke’s father would have had to say about what had happened just now, because in all the years he’d sat at this desk, he had never witnessed such a great surge of devotion as he’d seen today.

‘If you don’t mind me saying, Mr Hammond, I think you’ve forgotten something, so yer have.’

‘Oh?’ Turning from the window where he was enjoying his employees’ good humour, he asked, ‘What’s that then, Thomas?’

Thomas took off his spectacles, as he habitually did when about to say something serious. ‘The men may well have “made” the business, as you so put it. But it’s you they look up to, and it’s you that inspires them, so it is.’

Having said his piece, he smiled to himself, discreetly blinked away a tear, and got on with his paperwork.

Later, Luke discreetly observed his employees, content at their work. He wondered what his father would think about this new turn of events. A twist of regret spiralled up in him as he reflected, and not for the first time, how he had no son to hand the business on to. Somehow, a child had not happened, and now it seemed all too late.

His thoughts turned to Sylvia.

Why had she given herself to a man like Arnold Stratton? Had he himself let her down as a husband? Had he worked too long and hard, sometimes building the business, sometimes trying to keep it afloat? Had she been lonely? Was it all his fault? Time and again, he had asked himself that.

And yet when he looked back, he had not seen any real signs that she was unhappy or lonely. At that time she had many friends; all of whom had since deserted her when she needed them most.

She had been a busy, fulfilled woman who lived life to the full. He made sure they spent a great deal of time together. Since the day he met her, he had loved her with all his heart and had believed she loved him the same.

And yet she had found the need to seek out a man like Arnold Stratton. It was a sobering thought. He could not understand. Had she never really loved him? Did she secretly yearn for the greater excitement he could not give her?

And now, with the lovemaking ended and her injuries taking their toll, there would never be a child and she was like a child herself: helpless; frightened. All she had in the world were the two people who really cared: himself, and the devoted Edna. But, though they would do anything for her, they could not perform the miracle she needed.

In his mind’s eye he could see his painting of Sylvia. In that painting he had captured her beauty and serenity. If he was to paint her now, the fear and madness, however slight, would show in her eyes and mar her beauty. Arnold Stratton had done that and now he was in prison for what had happened to Sylvia. And rightly so!

The feeling of sorrow turned to a cold and terrible rage. If only he could have stopped it happening. If he could get his hands on that bastard, he’d make him pay for every minute he and Sylvia had been together. He imagined them in bed, naked, and his mind was frantic.

Stratton was where he belonged. A long spell in prison was not punishment enough for what that monster had done.

His unsettled thoughts shifted to another painting, hidden away in his sanctuary. It was a painting of another young woman. A woman with mischief in her eyes and the brightest, most endearing smile. A woman not of the same kind of beauty as his wife, but with something he could not easily define, not even in the painting of her.