По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

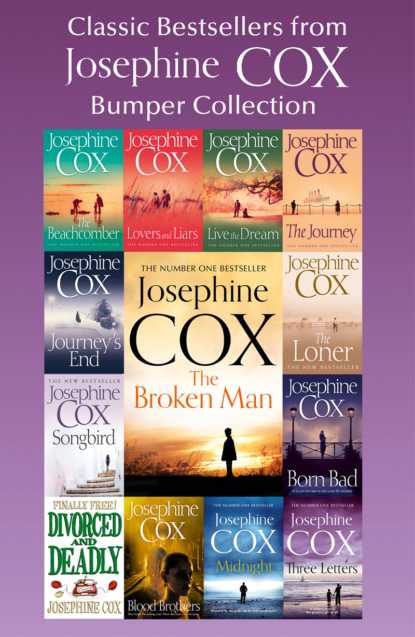

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Don’t get yourself worked up, old-timer.’ Danny knew how frustrated the old man was, and how desperately he wanted rid of Clem Jackson – as they all did.

‘’Course I’m worked up!’ Keeping his voice low so the child couldn’t hear, the old fella hitched himself up in the bed. ‘He’s a thorn in my side, that’s what he is.’ Leaning closer, he imparted intimately, ‘There’s summat bad happening in this house. I don’t know what it is, but I can sense it.’

Startled by the old man’s comment, Danny asked worriedly, ‘Whatever d’you mean by that?’

Lying back on his pillow the old man sniffed and coughed and for a while he tried hard to think what it might be that played so heavy on his mind. ‘I don’t know exactly what it is,’ he said finally. ‘All I know is there’s summat secretive goin’ on. I can feel it in me bones.’ He looked at Danny. ‘Did you know he’s fetching women of a certain sort back to the farm? I’ve seen the randy buggers from me window, an’ it don’t need no brains to guess what they’re here for.’

Danny had suspected as much. ‘What do Aggie and Emily have to say about it?’

‘They haven’t said owt, and they wouldn’t.’ He grinned from ear to ear. ‘I know more than they think.’

Though he was not one for gossip, Danny was intrigued. ‘In what way?’

Implying a secret, the old man tapped his nose. ‘Folks often talk to theirselves,’ he said. ‘Sometimes in their sleep and sometimes when they’re on their own and think nobody’s listening. If there’s bad things playing on their minds, they say ’em out loud. I know, ’cause I’ve ’eard it all with me own ears.’ His bushy eyebrows merged in a frown. ‘Secrets! Things like that!’

Hearing a door close somewhere downstairs, he dropped his voice to a whisper. ‘I know about things that went on a long time ago. I’ve never said, and I never will. But I don’t like it. One o’ these days, I intend doing summat about it an’ all!’

Growing anxious, he began struggling to sit up, angered when he fell back against the pillow. ‘Damn it! I’m useless. Bloody useless!’

Danny helped him. ‘You’re getting too excited,’ he told him. ‘Lie still and stop your worrying.’ He didn’t know what the old man meant by the things he’d said but, having been warned that Mr Ramsden’s mind was beginning to wander, he put it all down to that. ‘Emily will be along any minute,’ he said comfortingly. ‘Aggie too. She said to tell you she’d be up to change the bedlinen.’

The old man chuckled. ‘Fuss, fuss! Why is it women allus have to be doing summat?’

‘They love you, that’s why.’ Danny was grateful that, for the time being, Emily’s grandfather appeared to have forgotten what had got him so agitated.

‘Oh, I know they love me all right.’ Thomas Isaac gave him a naughty wink. ‘I know summat else too.’

‘And what’s that?’

‘I know you love my Emily.’ He had a twinkle in his eye. ‘I’m right, aren’t I?’

Danny laughed. ‘Yes, you’re right.’

‘And do you love her enough to wed her?’

‘If she’d have me, which she won’t.’

‘Keep on trying,’ the old man urged. ‘Don’t take no for an answer. Wear the lass down! She’ll soon get fed up saying no.’

Outside, balancing the cup and saucer while she opened the door, Emily caught the gist of that last conversation.

Not you an’ all, Grandad, she tutted to herself. It seemed the world and his friend were trying to match her to Danny. But there was a stirring of guilt in her heart. If both her mam and her grandad thought it best for her and Danny to be wed, happen she ought to seriously consider what they were saying.

When she opened the door the two men fell silent. ‘There you are!’ Addressing Grandad, she told him, ‘Mam’s sent a fresh cup of tea for you.’

Hoping she hadn’t heard what was said, Danny got out of the chair. ‘Sit here,’ he suggested. ‘I’d best make tracks anyway, or the customers will be stringing me up, along with the horse!’

While Emily served his tea, the old fella gave Danny a crafty wink. ‘Don’t forget what I told you,’ he said connivingly.

Danny returned his smile. ‘I won’t.’

Emily didn’t let on how she’d overheard the last part of their conversation. ‘What’s all the secrecy?’

‘Nothing for you to worry your head about!’ Grandad retorted, and realising she was being told to mind her own business, Emily said no more.

After a hug from Cathleen and a warm smile from Emily, Danny prepared to leave. ‘Thank you for sitting with Gramps.’ Emily saw him to the top of the landing.

‘I always enjoy talking to Tom,’ Danny said. ‘Though he’s a force to be reckoned with, that’s for sure. Strong-willed and strong-minded, and a temper to go with it.’

‘He’s all of that,’ Emily answered with a chuckle. ‘So – we’ll see you tomorrow morning, will we?’

‘Try and keep me away,’ was his reply.

‘You’d best go now,’ she suggested. ‘We can’t have the customers lynching you, can we?’

‘Am I to understand it would bother you if they did?’ Danny asked hopefully.

Emily didn’t answer. Instead she smiled shyly and turned to leave him there. But then she was taken by surprise when he took hold of her and swung her round. ‘I love you, Emily Ramsden. No! Don’t say anything. I just wanted you to know that. So, now I’ve told you, I’ll be on my way.’

Before she could open her mouth, he was down the stairs and out the door like a scalded cat, leaving her feeling warm and content inside. It was a peculiar, if unsettling feeling.

Chapter 11 (#ulink_bf7e4fcb-b094-5284-be4b-1b519ebb339e)

AS ALWAYS, THE day was long and the work was hard, and on this particular August evening, the daylight lingered and the skies retained their clear blue lustre. Having drawn the horse and cart to a halt, Danny hurried across to the orchard, where Emily and her child were playing peek-aboo round the apple trees.

‘By! It were that hot in Blackburn town today, you could fry an egg on the pavement, so you could!’ he told them.

They came to greet him, Cathleen at full tilt in front, and Emily sauntering on behind. ‘It’s a wonder your milk didn’t go sour,’ she said.

‘I got rid of it all in good time,’ he explained, ‘though the churns do keep the milk cold, up to a point anyway.’

The child wasn’t interested in whether the milk had gone sour or not. She had bigger problems than that. ‘My swing’s broke,’ she told Danny. ‘Mam says she can mend it, but she can’t.’ She gave Emily a forgiving look. ‘It’s all right though,’ she promised, ‘’cause Danny will mend it now, won’t you, Danny? Please?’

Danny followed the two of them to the biggest, oldest apple tree in the orchard, where Cathleen’s broken swing hung down. ‘Let’s see now.’ Lifting the seat he examined the underneath.

‘Three times I’ve threaded the rope through the holes and tied the knot nice and big,’ Emily explained, ‘and it still keeps slipping through. It’s dangerous. I think the timber’s rotten.’

‘Aye.’ Danny slipped the seat off altogether. ‘You’re absolutely right. This wood is as soft as muck.’ He poked his finger through the holes. ‘That’s why the holes keep breaking open.’ He swung the child into his arms. ‘It can’t be mended. It’s not safe,’ he told her. ‘It needs a new seat.’

‘Can you make me one – can you?’ The little girl’s lips wobbled.

Danny chucked her under the chin. ‘Hey! We’ll have no tears, if you don’t mind. Tears make me sad, and I don’t like being sad.’

Cathleen smiled through her big wet eyes. ‘Will you make me a new seat, please, Danny?’

He laughed out loud. ‘I’ll make you the finest seat in the whole of Lancashire. I’ll even find a new length of rope in case that’s going rotten too. Now then, Cathleen, what d’you say to that?’

‘I say yes!’ And she planted a grateful smacker on his face.