По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

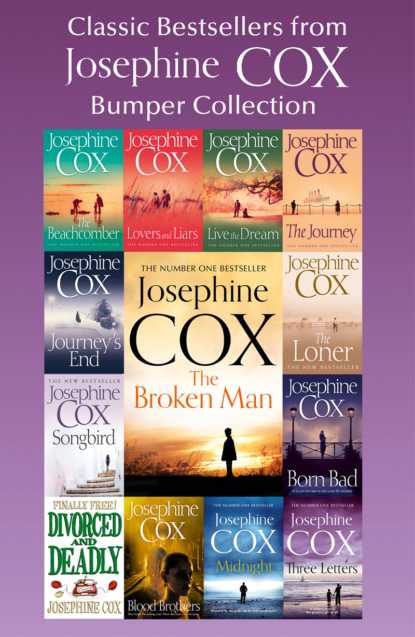

Classic Bestsellers from Josephine Cox: Bumper Collection

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The girl shook them each by the hand. ‘I go by the name of Rosie Taylor,’ she said. ‘My father is Lonnie Taylor, of Taylor’s Carriers.’ Her smile was one of relief. ‘If you can put that second barge back on the canal, we’ll both be very grateful to you.’

Archie was curious. ‘How old are you, to be taking on the responsibility of a business?’

‘Older than you think.’

‘And how old is that?’

‘You’re a cheeky devil!’

‘Born like it,’ he chuckled. ‘So, how old?’

‘You tell me.’

‘Eighteen, mebbe nineteen?’

‘I’m twenty-two next birthday.’

She was the same age as himself, John noted. Archie was about to ask another question, when John gave him one of his warning glances. ‘Right then!’ the little man finished the conversation. ‘We’d best get on.’

When she ushered them into the barge, both men were impressed by the interior. ‘I’ve been on many a ship in my time,’ Archie remarked. ‘This is the first occasion I’ve been on a barge, and I don’t mind telling you, I’m amazed. I always thought they must be too narrow for a man to move about freely, but there’s room aplenty.’

‘People are always surprised at how roomy they are.’ Rosie handed him a cup of sarsaparilla.

‘Given the chance, I could laze about here all day.’ Seating himself on the little green sofa, he supped contentedly at his drink.

John considered the barge to be warm and welcoming, much like Rosie herself, he thought. Moreover, with the little stove, the oblong peg-rug and comfortable furnishings, she had made it a home. ‘It’s a credit to you,’ he said, and meant it.

In no time at all, they arrived at their destination. ‘There she is.’ Pointing to the rotting hull, Rosie slowed the barge.

Manoeuvring the vessel into the bank, she tied it up. ‘Before you offer to repair her, you might like to take stock of the damage.’

All three disembarking, they walked along the towpath to where the barge lay, lopsided, half-hidden by the undergrowth. ‘Careful now!’ Rosie warned. ‘The ground lies a bit swampy just here.’

They were soon up to their ankles in water and mud, with Archie complaining tetchily. ‘I’ll leave you two to get on with it. I’m finding my way to higher ground.’

Rosie smiled as she watched him leave. ‘He’s a character, isn’t he?’

John chuckled. ‘You could say that.’

She drew his attention to the hull. ‘What do you think?’

First he crawled all over the boat. Rosie had been right when she said the hole was huge. The central timbers immediately round the hole had rotted right through and now, after months at the mercy of the elements, there were a number of other timbers in dire need of repair, and some that would have to be replaced.

John’s investigation was thorough and conclusive. Apart from the huge, gaping hole and the damaged timbers, the engine was rusted and the chimney was smashed – but that was easily fixed, he thought. Then there was the difficult task of lifting the whole thing out of the bog, where it had settled deep. As far as he could see, shifting the barge would be no easy matter.

‘So, is she worth repairing?’ Rosie was behind him every step he took.

‘She’ll be good as new,’ he promised. ‘But this is the picture as far as I can tell. First off, you’ll need to buy a whole new batch of timbers. The engine looks to be seized, and the chimney’s smashed to a pulp.’ There was something else too. ‘I’ll need a yard to work in.’

Rosie apologised. ‘We don’t have a yard,’ she told him. ‘And the only decent yards round here are owned by the Armitage brothers.’ She sighed. ‘You saw the feud going on between those two, so you can guess how it is. Even if Jacob Armitage talked his brother Ronnie into letting you use part of one of their buildings, the favour wouldn’t come cheap.’

John wondered if he might be able to repair the barge right here on site. ‘We’d be dependent on the weather, o’ course, but it could be done. Mind you, we’d need to get her to higher ground.’ As he spoke, he walked to the top of the mound.

Rosie walked beside him. ‘I’m sure I could arrange that,’ she said thoughtfully. ‘But before you decide, there’s something I need to tell you.’ She paused, almost afraid to go on. ‘You see, I haven’t been completely honest with you.’

Feeling uneasy, John wanted to know, ‘What is it?’

She hesitated again, before telling him in a rush, ‘These past eighteen months have been awful hard without Dad in charge.’

John sympathised. ‘I can understand that.’

‘I’ve carried on the best I know how, and at last things are picking up, but even then, there isn’t enough money in the pot to pay you for any work you might do.’

‘I’ll do the work,’ he said. ‘You can pay me when you’re able.’

‘That won’t do.’ She was adamant. ‘My father has never owed a penny in his entire life and I wouldn’t want to be the one to let him down. So, if you’re interested, I have a proposition.’

With nothing much as yet to fall back on, John was more than interested. ‘Go on. I’m listening.’

Rosie outlined her plan. ‘If you can put the barge back on the canal, there’s a chance it will double the work. And if it doubles the work, it doubles the income. The trouble is, there’s only me to keep it all going, and according to the doctor, Dad may never work again.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that, Rosie.’ In a strange way he felt as though he’d known this young woman all his life. She was so open and easy to get along with.

Rosie continued, ‘So what I propose is this. If you repair the narrowboat, and come to work alongside me, I won’t pay you in money.’ She wondered how he would react to what she was about to say. ‘Instead, it would make more sense to offer you a partnership … say twenty per cent?’

John refused without hesitation. ‘I can’t accept that. Besides, I thought it was your father’s business. What in God’s name would he have to say about such a crazy idea?’

Rosie wouldn’t let it go. ‘It’s not so crazy if you think about it.’ Brushing aside his protests, she called his attention to the facts. ‘Look. First of all, I’m limping along with only one barge. I can’t meet all the bills, and I can’t borrow because we’ve reached our limit with the bank, so it’s a certainty that before too long I’ll have to call it a day – and that would break Dad’s heart. He’s run this business since he was a lad. Taylor’s Carriers is his pride and joy, and now he’s had to entrust it to me.’ Close to tears, she said quietly, ‘I don’t want to be the one who lets it all fall apart.’

John was deeply moved, but there were still questions to be answered. ‘From what I saw back there, you were offloading a heavy cargo. If you don’t mind me saying, that one job alone must have brought in a pretty penny?’

She gave a small, wry laugh. ‘It’s the only job I’ve had all week,’ she confessed. ‘What’s more, it won’t fetch a pretty penny as you put it, because the Armitage brothers know how to take advantage when somebody’s drowning. The young one, Ronnie, will cut you to the bone, and when you do finally get paid, it barely returns what you’ve spent out in the first place!’

She persisted with her idea. ‘So you see, with the other barge and you together, I know we’ll get more work. Men have little respect for a woman at the helm. A man likes to deal with a man, you should know that.’

John did know that, but, ‘Times are changing,’ he told her.

He thought of Emily and her mother and of how, when Aggie’s husband went off, she and Emily kept Potts End Farm going almost single-handed. He was so proud of Emily. He missed and loved her, and always would. His thoughts went next to his Auntie Lizzie, who had kept a home for him all the time he was growing up. She had worked in all weathers to bring in a few coppers to pay the bills. They were strong women, all of them, and he loved and respected them for it.

Rosie’s voice penetrated his thoughts. ‘Most of the cargo gets shifted on the order of a man, and they don’t like to deal with women, unless like the brothers, they’re trying to get it done on the cheap.’

John could see her point, but, ‘All I know is, your father would not take kindly to you offering me a fifth of his business.’

‘What if he was to agree?’

‘Well now, that might be different.’

‘Consider it done,’ she said. ‘I know Father would be glad for me to have a man helping out, until he gets on his feet again.’