По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

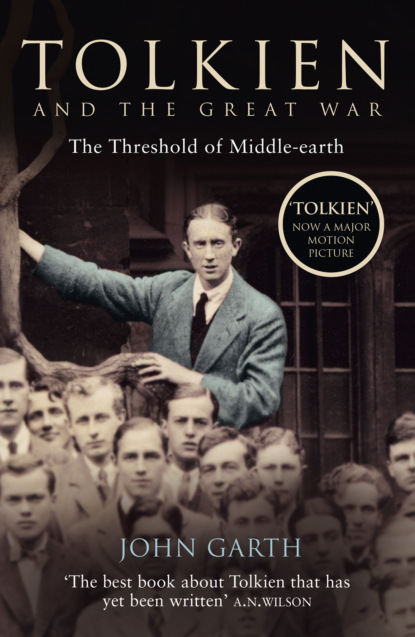

Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That is for ever England.

G.B. Smith admired Brooke’s poetry and thought Tolkien should read it, but the poems Tolkien wrote when he settled back in at 59 St John Street at the end of the month could hardly have been more different. On Tuesday 27 April he set to work on two ‘fairy’ pieces, finishing them the next day. One of these, ‘You and Me and the Cottage of Lost Play (#litres_trial_promo)’, is a 65-line love poem to Edith. Hauntingly, it suggests that when they first met they had already known each other in dreams:

You and me – we know that land

And often have been there

In the long old days, old nursery days,

A dark child and a fair.

Was it down the paths of firelight dreams

In winter cold and white,

Or in the blue-spun twilit hours

Of little early tucked-up beds

In drowsy summer night,

That You and I got lost in Sleep

And met each other there –

Your dark hair on your white nightgown,

And mine was tangled fair?

The poem recalls the two dreamers arriving at a strange and mystical cottage whose windows look towards the sea. Of course, this is quite unlike the urban setting in which he and Edith had actually come to know each other. It was an expression of tastes that had responded so strongly to Sarehole, Rednal, and holidays on the coast, or that had been shaped by those places. But already Tolkien was being pulled in opposite directions, towards nostalgic, rustic beauty and also towards unknown, untamed sublimity. Curiously, the activities of the other dreaming children at the Cottage of Lost Play hint at Tolkien’s world-building urges, for while some dance and sing and play, others lay ‘plans / To build them houses, fairy towns, / Or dwellings in the trees’.

A debt is surely owed to Peter Pan’s Neverland. Tolkien had seen J. M. Barrie’s masterpiece at the theatre as an eighteen-year-old in 1910, writing afterwards: ‘Indescribable but (#litres_trial_promo) shall never forget it as long as I live.’ This was a play aimed squarely at an orphan’s heart, featuring a cast of children severed from their mothers by distance or death. A chiaroscuro by turns sentimental and cynical, playful and deadly serious, Peter Pan took a rapier to mortality itself – its hero a boy who refuses to grow up and who declares that ‘To die will be an awfully big adventure.’

But Tolkien’s idyll, for all its carefree joy, is lost in the past. Time has reasserted itself, to the grief and bewilderment of the dreamers.

And why it was Tomorrow came,

And with his grey hand led us back;

And why we never found the same

Old cottage, or the magic track

That leads between a silver sea

And those old shores and gardens fair

Where all things are, that ever were –

We know not, You and Me.

The companion piece Tolkien wrote at the same time, ‘Goblin Feet (#litres_trial_promo)’, finds us on a similar magic track surrounded by a twilight hum of bats and beetles and sighing leaves. A procession of fairy-folk approaches and the poem slips into an ecstatic sequence of exclamations.

O! the lights: O! the gleams: O! the little tinkly sounds:

O! the rustle of their noiseless little robes:

O! the echo of their feet – of their little happy feet:

O! their swinging lamps in little starlit globes.

Yet ‘Goblin Feet’ turns in an instant from rising joy to loss and sadness, capturing once again a very Tolkienian yearning. The mortal onlooker wants to pursue the happy band, or rather he feels compelled to do so; but no sooner is the thought formed than the troop disappears around a bend.

I must follow in their train

Down the crooked fairy lane

Where the coney-rabbits long ago have gone,

And where silverly they sing

In a moving moonlit ring

All a-twinkle with the jewels they have on.

They are fading round the turn

Where the glow-worms palely burn

And the echo of their padding feet is dying!

O! it’s knocking at my heart –

Let me go! O! let me start!

For the little magic hours are all a-flying.

O! the warmth! O! the hum! O! the colours in the dark!

O! the gauzy wings of golden honey-flies!

O! the music of their feet – of their dancing goblin feet!

O! the magic! O! the sorrow when it dies.

Enchantment, as we know from fairy-tale tradition, tends to slip away from envious eyes and possessive fingers – though there is no moral judgement implied in ‘Goblin Feet’. Faërie and the mortal yearning it evokes seem two sides of a single coin, a fact of life.

In a third, slighter, piece that followed on 29 and 30 April, Tolkien pushed the idea of faëry exclusiveness further. ‘Tinfang Warble (#litres_trial_promo)’ is a short carol, barely more than a sound-experiment, perhaps written to be set to music, with its echo (‘O the hoot! O the hoot!’) of the exclamatory chorus of ‘Goblin Feet’. In part, the figure of Tinfang Warble is descended in literary tradition from Pan, the piper-god of nature; in part, he comes from a long line of shepherds in pastoral verse, except he has no flock. Now the faëry performance lacks even the communal impulse of the earlier poem’s marching band. It is either put on for the benefit of a single glimmering star, or it is entirely solipsistic.