По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

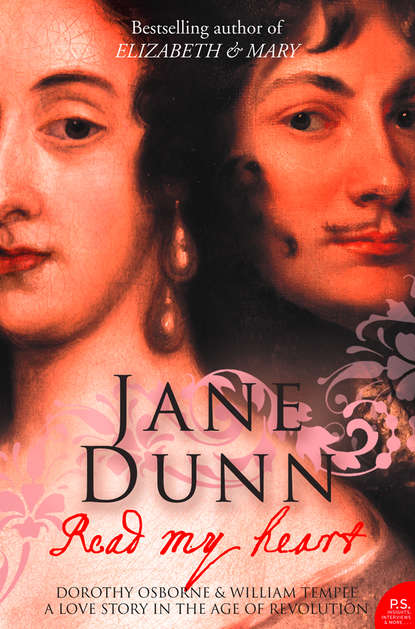

Read My Heart: Dorothy Osborne and Sir William Temple, A Love Story in the Age of Revolution

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

* (#ulink_51feee7c-032e-5848-bfd7-5dabfc466c54)Ralph Cudworth (1617–88), an English philosopher opposed to Thomas Hobbes and leader of the Cambridge Platonists. Master of Clare Hall and then of Christ’s College, Cambridge and professor of Hebrew. He had an intellectual daughter, Damaris, Lady Masham, who became a friend of the philosophers John Locke and Leibniz.

† (#ulink_94cb0fca-8e68-528d-8d46-2fcbc511d63b)The Cambridge Platonists were a group of philosophers in the middle of the seventeenth century who believed that religion and reason should always be in harmony. Although closer in sympathy to the Puritan view, with its valuing of individual experience, they argued for moderation in religion and politics and like Abelard promoted a mystical understanding of reason as a pathway to the divine.

* (#ulink_94cb0fca-8e68-528d-8d46-2fcbc511d63b)Henry St John, Viscount Bolinbroke (1678–1751), an ambitious and unscrupulous politician and favourite of Queen Anne’s. He turned his brilliant gifts to writing philosophical and political tracts. His philosophical writings were closely based on the philosopher John Locke’s (1632–1704) inductive approach to knowledge, reasoning from observations to generalisations (to which Ralph Cudworth and the Cambridge Platonists were opposed). Few were published in his lifetime. He died, after a long life, a disappointed man.

* (#ulink_4f5927d8-8375-5a8d-b29e-c57b349db6fb)The use of uncouched is interesting. It can mean rampant, the opposite of the heraldic term couchant, but more to the point uncouched also refers to an animal that has been driven from its lair. The image of a beast unleashed is very appropriate here, for it expressed Osborne’s fear, fascination and recoil from homosexuality: already he had referred to it as ‘noisom Bestiality’, but also that telling parenthesis revealed a curiosity about the ‘delight I know not’.

* (#ulink_5e5da915-7ff4-5ea7-a283-34b6f2058fda)Religio Medici was Sir Thomas Browne’s (1605–82) famous meditation on matters of faith, humanity and love, first published in 1642, reprinted often and translated into many languages. As a doctor and a Christian he illuminated his tolerant, wide-ranging thesis with classical allusions, poetry and philosophy.

† (#ulink_5e5da915-7ff4-5ea7-a283-34b6f2058fda)Written by Samuel Butler (1613–80), Hudibras was a mock romance in the style of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, written in three parts, each with three cantos of heavily satirical verse, published 1662–80. With his framework of a Presbyterian knight Sir Hudibras and his sectarian squire Ralpho embarked on their quest, Butler poked lethal fun at the wide world of politics, theological dogma, scholasticism, alchemy, astrology and the supernatural.

‡ (#ulink_d2c283e5-1f7b-5c34-ab54-3f0e0c2d3a90)Laurence Hyde, 4th Earl of Rochester (1641–1711), was the second son of the great politician and historian the Earl of Clarendon. A royalist, he rose to power and influence at Charles II’s restoration and was made an earl in 1681, becoming lord high treasurer under his brother-in-law James II. His nieces became Queens Mary and Anne.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_70a0520f-2bf6-5a7b-b88d-b3d2bcfe06d9)

Time nor Accidents Shall not Prevaile (#ulink_70a0520f-2bf6-5a7b-b88d-b3d2bcfe06d9)

I will write Every week, and noe misse of letters shall give us any doubts of one another, Time nor accidents shall not prevaile upon our hearts, and if God Almighty please to blesse us, wee will meet the same wee are, or happyer; I will doe all you bid mee, I will pray, and wish and hope, but you must doe soe too then; and bee soe carfull of your self that I may have nothing to reproche you with when you come back.

DOROTHY OSBORNE, letter to William Temple

[11/12 February 1654]

ALTHOUGH TRAVEL ABROAD was accepted as an important part of the education of a young English gentleman of the seventeenth century, a young unmarried lady was denied any such freedom; even travelling at home she was expected to be chaperoned at all times. For her to venture abroad to educate the mind was an almost inconceivable thought. But much more unsettling to the authority of the family, to her reputation and the whole social foundation of their lives was the idea that a young man and woman might meet outside the jurisdiction of their parents’ wishes, free to make their own connections, even to fall in love.

Not only were serendipitous meetings like that of Dorothy and William unorthodox for young people in their station of life, the idea that they themselves could choose whom they wanted to marry on the grounds of personal liking, even love, was considered a short cut to social anarchy, even lunacy. With universal constraints and expectations like this it was remarkable that they should ever have met, let alone discovered how much they really liked each other. Their candour in expressing their feelings in private also belied the carefulness of their public face. Dorothy admitted to William her eccentricity in this: ‘I am apt to speak what I think; and to you have soe accoustumed my self to discover all my heart, that I doe not beleeve twill ever bee in my power to conceal a thought from you.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The grip that family and society’s disapproval exerted was hard to shake off. In a later essay when he himself was old, William likened the denial of the heart to a kind of hardening of the arteries that too often accompanied old age: ‘youth naturally most inclined to the better passions; love, desire, ambition, joy,’ he wrote. ‘Age to the worst; avarice, grief, revenge, jealousy, envy, suspicion.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Dorothy had youth on her side and laid claim to all those better passions, but it was the unique and shattering effects of civil war that broke the constraints on her life and sprang her into the active universe of men. Although personally strong-minded and individualistic, her intent was always to comply with her family’s and society’s expectations, for she was an intellectual and reflective young woman and not a natural revolutionary. But for the war she would have been safely sequestered at home, visitors vetted by her family, her world narrowed to the view from a casement window. In fact this containment is what she had to return to, but for a while she was almost autonomous, a traveller across the sea – accompanied by a young brother, true, but he more inclined to play the daredevil than the careful chaperone.

As they both set off on their travels, heading on their different journeys towards the Isle of Wight, both Dorothy and William would have had all kinds of prejudice and practical advice ringing in their ears. Travel itself was fraught with danger: horses bolted, coaches regularly overturned, cut-throats ambushed the unwary and boats capsized in terrible seas. Disease and injury of the nastiest kinds were everyday risks with none of the basic palliatives of drugs for pain relief and penicillin for infection, or even a competent medical profession more likely to heal than to harm. The extent of the rule of law was limited and easily corrupted, and dark things happened under a foreign sun when the traveller’s fate would be known to no one.

As William Temple began his adventures for education and pleasure, Dorothy Osborne was propelled by very different circumstances into hers. Travel was hazardous, but it was considered particularly so if you were female. One problem was the necessity for a woman of keeping her public reputation spotless while inevitably attracting the male gaze, with all its hopeful delusions.

Lord Savile, in his Worldly Counsel to a Daughter, a more limited manual than Osborne’s Advice to a Son, was kindly and apologetic at the manifest unfairnesses of woman’s lot, yet careful not to encourage any daughter of his, or anyone else’s, to challenge the sacred status quo. He pointed out that innocent friendliness in a young woman might be misrepresented by both opportunistic men, full of vanity and desire, and women eager to make themselves appear more virtuous by slandering the virtue of their sisters, ‘therefore, nothing is with more care to be avoided than such a kind of civility as may be mistaken for invitation’. The onus was very much upon the young woman who had always to be polite while continually on guard lest her behaviour call forth misunderstanding and shame. She had to cultivate ‘a way of living that may prevent all coarse railleries or unmannerly freedoms; looks that forbid without rudeness, and oblige without invitation, or leaving room for the saucy inferences men’s vanity suggesteth to them upon the least encouragements’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Dorothy was often chided by William during their courtship for what he considered her excessive care for her good reputation and concern at what the world thought of her. With advice like this, it was little wonder that young women of good breeding felt that strict and suspicious eyes were ever upon them. A conscientious young woman’s behaviour and conversation had to be completely lacking in impetuousity and candour. It seemed humour also was a lurking danger. Gravity of demeanour at all times was the goal, for smiling too much (‘fools being always painted in that posture’) and – honour forbid – laughing out loud made even the moderate Lord Savile announce ‘few things are more offensive’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Certainly a woman was not meant to enjoy the society of anyone of the opposite sex except through the contrivance of family members, with a regard always to maintaining her honour and achieving an advantageous marriage.

After Dorothy and William’s fateful meeting on the Isle of Wight in 1648, they spent about a month together at St Malo, no doubt mostly chaperoned by Dorothy’s brother Robin, as travelling companions and explorers, both of the town and surrounding countryside, and more personally of their own new experiences and feelings. William would have met Sir Peter Osborne there, aged, unwell and in exile. Like the Temple family, the Osbornes were frank about their insistence that their children marry for money. Both Sir Peter Osborne and Sir John Temple were implacably set against any suggestion that Dorothy and William might wish to marry; rather it was a self-evident truth that their children had the more pressing duty to find a spouse with a healthy fortune to maintain the family’s social status and material security. For a short while neither father suspected the truth.

St Malo was an ancient walled city by the sea, at this time one of France’s most important ports. Yet it retained its defiant and independent spirit as the base for much of the notorious piracy and smuggling carried on off its rocky and intricate coast. This black money brought great wealth to the town and financed the building of some magnificent houses. There was much to explore either within the walls in the twisting narrow alleyways or on the heather-covered cliffs that dropped to the boiling surf below.

These days of happy discovery were abruptly terminated when William’s father heard of his son’s delayed progress, and the alarming reason for it. When Sir John Temple ordered William to extricate himself from this young woman and her dispossessed family and continue his journey into France, there was no doubt that William, at twenty, would obey. The impact of this wrench from his newfound love can only be conjectured but he wrote, during the years of their enforced separation, something that implied resentment at parental power and a pained resignation to the habit of filial submission: ‘for the most part, parents of all people know their children the least, so constraind are wee in our demanours towards them by our respect, and an awfull sense of their arbitrary power over us, wch though first printed in us in our childish age, yet yeares of discretion seldome wholly weare out’. As a young man he thought no amount of kindness could overcome the traditional gulf between parents and their children (as parents themselves, he and Dorothy strove to overcome such traditions), but freedom and confidence thrived between friends, he believed, implying a close friend (i.e. a spouse) mattered as much as any blood relation: ‘for kindred are friends chosen to our hands’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Dorothy made an equally bleak point in one of her early surviving letters in which she declared that many parents, taking for granted that their children refused anything chosen for them as a matter of course, ‘take up another [stance] of denyeing theire Children all they Chuse for themselv’s’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As William reluctantly travelled on to Paris, Dorothy remained with her father and youngest brother, and possibly her mother and other brothers too, at St Malo, hoping to negotiate a return to their home at Chicksands. Five years before, at the height of the first civil war, it had been ordered in parliament ‘that the Estate of Sir Peter Osborne, in the counties of Huntingdon, Bedford or elsewhere, and likewise his Office, be sequestred; to be employed for the Service of the Commonwealth’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Towards the end of 1648, however, peace negotiations between parliament and Charles I, in captivity in Carisbrooke Castle, were stumbling to some kind of conclusion. There was panic and confusion as half the country feared the king would be reinstated, their suffering having gained them nothing, while the other half rejoiced in a possible return to the status quo with Charles on his throne again and the hierarchies of Church and state comfortingly restored.

Loyal parliamentarians Lucy and her husband Colonel Hutchinson were in the midst of this turmoil. The negotiations, she wrote, ‘gave heart to the vanquished Cavaliers and such courage to the captive King that it hardened him and them to their ruin. This on the other side so frightened all the honest people that it made them as violent in their zeal to pull down, as the others were in their madness to restore, this kingly idol.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Revolution was in the air and, to general alarm, suddenly the New Model Army intervened in a straightforward military coup, taking control of the king, thereby pre-empting any further negotiations, and purging parliament of sympathisers. About 140 of the more moderate members of the Long Parliament were prevented from sitting, Sir John Temple among them. Only the radical or malleable remnants survived the vetting, 156 in all, and they became known for ever as the ‘Rump Parliament’. The king’s days were now numbered.

Dorothy and her family in France were part of an expatriate community who, away from the heat of the struggle, were subject to the general hysteria of speculation and wild rumour, brought across the Channel by letter and word of mouth, reporting the rapidly changing state at home. William was also in France, but by this time separated from Dorothy and alone in Paris. Revolution was in the air there too. ‘I was in Paris at that time,’ he wrote, referring to January 1649, ‘when it was beseig’d by the King

(#litres_trial_promo) and betray’d by the Parliament, when the Archduke Leopoldus advanced farr into France with a powerfull army, fear’d by one, suspected by another, and invited by a third.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was an alarming but exciting time to be at the centre of France’s own more half-hearted version of civil war, the Fronde,

(#litres_trial_promo) when not much blood was spilt but a great deal of debate and violent protest dominated the political scene. The Paris parlement had refused to accept new taxes and were complaining about the old, attempting to limit the king’s power. When the increasingly hated Cardinal Mazarin

(#litres_trial_promo) ordered the arrest of the leaders at the end of a long hot summer, there was rioting on the streets and out came the barricades. The court was forced to release the members of parlement and fled the city. Parlement’s victory was sealed and temporary order restored only by the following spring. Having left one kind of turmoil at home, William was embroiled in another, but was not in the mood to let that cramp his youthful style. At some time he met up with a friend, a cousin of Dorothy’s, Sir Thomas Osborne,

(#litres_trial_promo) and reported their good times in a later letter to his father: ‘We were great companions when we were both together young travelers and tennis-players in France.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was also while he was in Paris in its rebellious mood that William discovered the essays of Montaigne

(#litres_trial_promo) and perhaps even came across some of the French avant-garde intellectuals of the time. The most contentious were a group called the Libertins, among them Guy Patin, a scholar and rector of the Sorbonne medical school, and François de la Mothe le Vayer, the writer and tutor to the dauphin, who pursued Montaigne’s sceptical philosophies to more radical ends, questioning even basic religious tenets. Certainly from the writings of Montaigne and from the intellectual energy in Paris at the time – perhaps even the company of these controversial philosophers – William learned to enjoy a distinct freedom of thought and action that reinforced his natural independence and incorruptibility in later political life.

Just across the Channel, events were gathering apace. By January 1649 in London the newly sifted parliament had passed the resolutions that sidelined a less compliant House of Lords, allowing the Commons to ensure the trial of the king could proceed. There was terrific nervousness at home; even the most fiery of republicans was not sure of the legality of any such court. In a further eerie echo of the fate of his grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, Charles was brought hastily to trial, all the while insisting that the court had no legality or authority over him. On 20 January 1649 he appeared before his accusers in the great hall at Westminster. Like his grandmother too he had dressed for full theatrical effect, his diamond-encrusted Order of the Star of the Garter and of St George glittering majestically against the sombre inky black of his clothes. Charles was visibly contemptuous of the cobbled-together court and did not even deign to answer the charges against him, that he had intended to rule with unlimited and tyrannical power and had levied war against his parliament and people. He refused to cooperate, rejecting the proceedings out of hand as manifestly illegal.

All those involved were fraught with anxieties and fear at the gravity of what they had embarked on. As the tragedy gained its own momentum, God was fervently addressed from all sides and petitioned for guidance, His authority invoked to legitimise every action. Through the fog of these doubts Cromwell strode to the fore, his clarity and determination driving through a finale of awesome significance. God’s work was being done, he assured the doubters, and they were all His chosen instruments. It was clear to him that Charles had broken his contract with his people and he had to die. His charismatic certainty steadied their nerves.

The death sentence declared the king a tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy of the nation. There were frantic attempts to save his life. From France, Charles’s queen Henrietta Maria had been busy in exile trying to rally international support for her husband. Louis XIV, a boy king who was yet to grow into his pomp as the embodiment of absolute monarchy, now sent personal letters to both Cromwell and General Fairfax pleading for their king’s life. The States-General of the Netherlands also added their weight, all to no avail.

Charles I went to his death in the bitter cold of 30 January 1649. He walked from St James’s Palace to Whitehall, his place of execution. Grave and unrepentant, he faced what he and many others considered judicial murder with dignity and fortitude. As his head was severed from his body, the crowd who had waited all morning in the freezing air let out a deep and terrible groan, the like of which one witness said he hoped never to hear again. Charles’s uncompromising stand, the arrogance and misjudgements of his rule, the corrosive harm of the previous six years of civil wars, had made this dreadful act of regicide inevitable, perhaps even necessary, but there were few who could unequivocally claim it was just. There was a possibly apocryphal story passed on to the poet Alexander Pope, born some forty years later, that Cromwell visited the king’s coffin incognito that fateful night and, gazing down on the embalmed corpse, the head now reunited with the body and sewn on at the neck, was heard to mutter ‘cruel necessity’,

(#litres_trial_promo) in rueful recognition of the truth.