По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

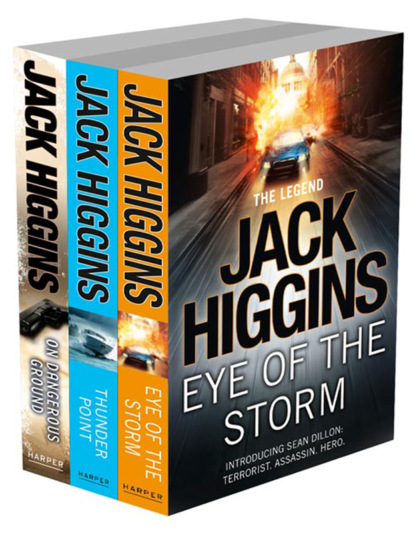

Sean Dillon 3-Book Collection 1: Eye of the Storm, Thunder Point, On Dangerous Ground

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Scenes of my youth,’ Dillon told him. ‘I’ve been working in London for years. Just in town for business overnight. Thought I’d like to see the old haunts.’

‘Suit yourself. There’s the Deepdene, but it’s not much, I’m telling you.’

A Saracen armoured car passed then and as they turned into a main road, they saw an army patrol. ‘Nothing changes,’ Dillon said.

‘Sure and most of those lads weren’t even born when the whole thing started,’ the driver told him. ‘I mean, what are we in for? Another hundred years war?’

‘God knows,’ Dillon said piously and opened his paper.

The driver was right. The Deepdene wasn’t much. A tall Victorian building in a mean side street off the Falls Road. He paid off the driver, went in and found himself in a shabby hall with a worn carpet. When he tapped the bell on the desk a stout, motherly woman emerged.

‘Can I help you, dear?’

‘A room,’ he said. ‘Just the one night.’

‘That’s fine.’ She pushed a register at him and took a key down. ‘Number nine on the first floor.’

‘Shall I pay now?’

‘Sure and there’s no need for that. Don’t I know a gentleman when I see one?’

He went up the stairs, found the door and unlocked it. The room was as shabby as he’d expected, a single brass bedstead, a wardrobe. He put his case on the table and went out again, locking the door, then went the other way along the corridor and found the backstairs. He opened the door at the bottom into an untidy backyard. The lane beyond backed on to incredibly derelict houses, but it didn’t depress him in the slightest. This was an area he knew like the back of his hand, a place where he’d led the British Army one hell of a dance in his day. He moved along the alley, a smile on his face, remembering, and turned into the Falls Road.

11

‘I remember them opening this place in seventy-one,’ Brosnan said to Mary. He was standing at the window of the sixth-floor room of the Europa Hotel in Great Victoria Street next to the railway station. ‘For a while it was a prime target for IRA bombers, the kind who’d rather blow up anything rather than nothing.’

‘Not you, of course.’

There was a slight, sarcastic edge which he ignored. ‘Certainly not. Devlin and I appreciated the bar too much. We came in all the time.’

She laughed in astonishment. ‘What nonsense. Are you seriously asking me to believe that with the British Army chasing you all over Belfast you and Devlin sat in the Europa’s bar?’

‘Also the restaurant on occasion. Come on, I’ll show you. Better take our coats, just in case we get a message while we’re down there.’

As they were descending in the lift, she said, ‘You’re not armed, are you?’

‘No.’

‘Good, I’d rather keep it that way.’

‘How about you?’

‘Yes,’ she said calmly. ‘But that’s different. I’m a serving officer of Crown forces in an active service zone.’

‘What are you carrying?’

She opened her handbag and gave him a brief glimpse of the weapon. It was not much larger than the inside of her hand, a small automatic.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘Rather rare. An old Colt .25. I picked it up in Africa.’

‘Hardly an elephant gun.’

‘No, but it does the job.’ She smiled bleakly. ‘As long as you can shoot, that is.’

The lift doors parted and they went across the lounge.

Dillon walked briskly along the Falls Road. Nothing had changed, nothing at all. It was just like the old days. He twice saw RUC patrols backed up by soldiers and once, two armoured troop carriers went by, but no one paid any attention. He finally found what he wanted in Craig Street about a mile from the hotel. It was a small, double-fronted shop with steel shutters on the windows. The three brass balls of a pawnbroker hung over the entrance with the sign ‘Patrick Macey’.

Dillon opened the door and walked into musty silence. The dimly lit shop was crammed with a variety of items. Television sets, video recorders, clocks. There was even a gas cooker and a stuffed bear in one corner.

There was a mesh screen running along the counter and the man who sat on a stool behind it was working on a watch, a jeweller’s magnifying glass in one eye. He glanced up, a wasted-looking individual in his sixties, his face grey and pallid.

‘And what can I do for you?’

Dillon said, ‘Nothing ever changes, Patrick. This place still smells exactly the same.’

Macey took the magnifying glass from his eye and frowned. ‘Do I know you?’

‘And why wouldn’t you, Patrick? Remember that hot night in June of seventy-two when we set fire to that Orangeman Stewart’s warehouse and shot him and his two nephews as they ran out. Let me see, there were the three of us.’ Dillon put a cigarette in his mouth and lit it carefully. ‘There was you and your half-brother, Tommy McGuire, and me.’

‘Holy Mother of God, Sean Dillon, is that you?’ Macey said.

‘As ever was, Patrick.’

‘Jesus, Sean, I never thought to see you in Belfast City again. I thought you were …’

He paused and Dillon said, ‘Thought I was where, Patrick?’

‘London,’ Patrick Macey said. ‘Somewhere like that,’ he added lamely.

‘And where would you have got that idea from?’ Dillon went to the door, locking it and pulled down the blind.

‘What are you doing?’ Macey demanded in alarm.

‘I just want a nice private talk, Patrick, me old son.’

‘No, Sean, none of that. I’m not involved with the IRA, not any more.’

‘You know what they say, Patrick, once in never out. How is Tommy these days, by the way?’

‘Ah, Sean, I’d have thought you’d know. Poor Tommy’s been dead these five years. Shot by one of his own. A stupid row between the Provos and one of the splinter groups. INLA were suspected.’

‘Is that a fact?’ Dillon nodded. ‘Do you see any of the other old hands these days? Liam Devlin for instance?’

And he had him there for Macey was unable to keep the look of alarm from his face. ‘Liam? I haven’t seen him since the seventies.’