По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

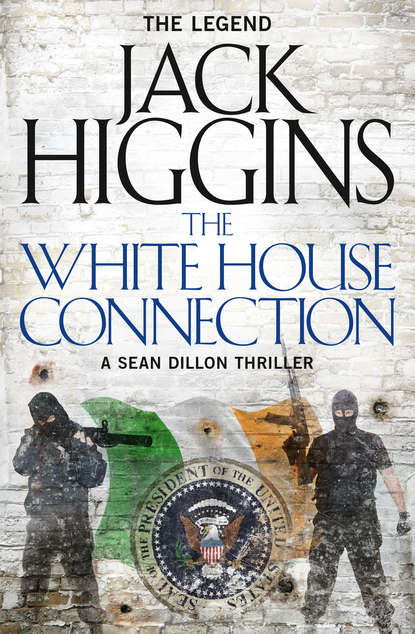

The White House Connection

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Helen held her husband’s hand. He had aged ten years in the past few days – a man once spry and vigorous now seemed as if he’d never been young. Rest in peace, she thought. But that’s what it was supposed to have been for. Peace in Ireland, and those bastards destroyed him. No trace. It’s as if he’s never been, she thought, frowning, unable to weep. That can’t be right. There’s no justice, none at all in a world gone mad. The priest intoned: ‘I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.’

Helen shook her head. No, not that. Not that. I don’t believe any more, not when evil walks the earth unpunished.

She turned, leaving the astonished mourners, taking her husband with her, and walked away. Hedley followed, the umbrella held over them.

Her father, unable to attend the funeral because of illness, died a few months later, and left her a millionaire many times over. The management team that controlled the various parts of the corporation were entirely trustworthy and headed by her cousin, with whom she’d always been close, so it was all in the family. She devoted herself to her husband, a broken man, who himself died a year after his son.

As for Helen, she gave a certain part of her activities to charitable work and spent a great deal of time at Compton Place, although the one thousand acres that went with the house were leased out for large-scale farming.

To a certain extent, Compton Place was her salvation because of its fascinating location. A mile from the coast of the North Sea, that part of Norfolk was still one of the most rural areas of England, full of winding narrow lanes and places with names like Cley-next-the-Sea, Stiffkey and Blakeney, little villages found unexpectedly and then lost, never to be found again. It was all so timeless.

From the first time Roger had taken her there, she had been enchanted by the salt marshes with the sea mist drifting in, the shingle and sand dunes and the great wet beaches when the tide was out.

From her days as a child growing up in Cape Cod, she had loved the sea and birds and there were birds in plenty in her part of Norfolk: Brent geese from Siberia, curlews, redshanks and every kind of seagull. She loved walking or cycling along the dykes, none of them less than six feet high, that passed through the great banks of reeds. It gave her renewed energy every time she breathed in the salt sea air or felt the rain on her face.

The house had originally been built in Tudor times, but was mainly Georgian with a few later additions. The large kitchen was a post-war project, lovingly created in country style. The dining room, hall, library, and the huge drawing room, were panelled in oak. There were only six bedrooms now, for others had been developed into bathrooms or dressing rooms at various stages.

With the estate leased to various farmers, she had retained only six acres around the house, mainly woodland, leaving two large lawns and another for croquet. A retired farmer came up from the village from time to time to keep things in order, and when they were in residence, Hedley would get the tractor out and mow the grass himself.

There was a daily housekeeper named Mrs Smedley, and another woman from the village helped her with the cleaning when necessary. All this sufficed. It was a calm and orderly existence that helped her return to life. And the villagers helped, too.

The laws of the British aristocracy are strange. As Roger Lang’s wife, she was officially Lady Lang. Only the daughters of the higher levels of the nobility were allowed to use their Christian names, but the villagers in that part of Norfolk were a strange, stubborn race. To them she was Lady Helen, and that was that. It was an interesting fact that the same attitude pertained in London society.

Any help anyone needed, she gave. She attended church every Sunday morning and Hedley sat in the rear pew, always correctly attired in his chauffeur’s uniform. She was not above visiting the village pub of an evening for a drink or two, and there, too, Hedley always accompanied her and, though you might not think it, was totally accepted by those taciturn people ever since an extraordinary event some years past.

An incredibly high tide combined with torrential rain had caused the water to rise in the narrow canal that passed through the village from the old disused mill. Soon, it was overflowing into the street and threatening to engulf the village. All attempts to force open the lock gate which was blocking the water proved futile, and it was Hedley who plunged chest deep into the water with a crowbar, diving under the surface again and again until he managed to dislodge the ancient locking pins and the gate burst open. At the pub, he had never been allowed to pay for a drink again.

So, although it had lost its savour, life could have been worse – and then Lady Helen received an unexpected phone call, one that in its consequences would prove just as catastrophic as that other call two years earlier, the call that had announced the death of her son.

‘Helen, is that you?’ The voice was weak, yet strangely familiar.

‘Yes, who is this?’

‘Tony Emsworth.’

She remembered the name well: a junior officer under her husband many years ago, later an Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office. She hadn’t seen him for some time. He had to be seventy now. Come to think of it, he hadn’t been at either Peter’s funeral or her husband’s. She’d thought that strange at the time.

‘Why, Tony,’ she said. ‘Where are you?’

‘My cottage. I’m living in a little village called Stukeley now, in Kent. Only forty miles from London.’

‘How’s Martha?’ Helen asked.

‘Died two years ago. The thing is, Helen, I must see you. It’s a matter of life and death, you could say.’ He was racked by coughing. ‘My death, actually. Lung cancer. I haven’t got long to go.’

‘Tony. I’m so sorry.’

He tried to joke. ‘So am I.’ There was an urgency in his voice now. ‘Helen, my love, you must come and see me. I need to unburden myself of something, something you must hear.’

He was coughing again. She waited until he’d stopped. ‘Fine, Tony, fine. Try not to upset yourself. I’ll drive down to London this afternoon, stay overnight in town, and be with you as soon as I can in the morning. Is that all right?’

‘Wonderful. I’ll see you then.’ He put down the phone.

She had taken the call in the library. She stood there frowning, slightly agitated, then opened a silver box, took out a cigarette and lit it with a lighter Roger had once given her made from a German shell.

Tony Emsworth. The weak voice, the coughing, had given her a bad shake. She remembered him as a dashing Guards captain, a ladies’ man, a bruising rider to hounds. To be reduced to what she had just heard was not pleasant. Intimations of mortality, she thought. Death just round the corner, and there had been enough of that in her life.

But there was another, secret reason, something even Hedley knew nothing about. The odd pain in the chest and arm had given her pause for thought. She’d had a private visit to London recently, a consultation with one of the best doctors in Harley Street, tests and scans at the London Clinic.

It reminded her of a remark Scott Fitzgerald had made about his health: ‘I visited a great man’s office and emerged with a grave sentence.’ Something like that. Her sentence had not been too grave. Heart trouble, of course. Angina. No need to worry, my dear, the professor had said. You’ll live for years. Just take the pills and take it easy. No more riding to hounds or anything like that.

‘And no more of these,’ she said softly, and stubbed out the cigarette with a wry smile, remembering that she’d been saying that for months, and went in search of Hedley.

Stukeley was pleasant enough: cottages on either side of a narrow street, a pub, a general store and Emsworth’s place, Rose Cottage, on the other side of the church. Lady Helen had phoned before leaving London to give him the time and he was expecting them, opening the door to greet them, tall and frail, the flesh washed away, the face skull-like.

She kissed his cheek. ‘Tony, you look terrible.’

‘Don’t I just?’ He managed a grin.

‘Should I wait in the Merc?’ Hedley asked.

‘Nice to see you again, Hedley,’ Emsworth said. ‘Would it be possible for you to handle the kitchen? I let my daily go an hour ago. She’s left sandwiches, cakes and so on. If you could make the tea.…’

‘My pleasure,’ Hedley told him, and followed them in.

A log fire was burning in the large open fireplace in the sitting room. Beams supported the low ceiling and there was comfortable furniture everywhere and Indian carpets scattered over the stone-flagged floor.

Emsworth sat in a wing-backed chair and put his walking stick on the floor. A cardboard file was on the coffee table beside him.

‘There’s a photo over there of your old man and me when I was a subaltern,’ he said.

Helen Lang went to the sideboard and examined the photo in its silver frame. ‘You look very handsome, both of you.’

She returned and sat opposite him. He said, ‘I didn’t attend Peter’s funeral. Missed out on Roger’s, too.’

‘I had noticed.’

‘Too ashamed to show my face, ye see.’

There was something here, something unmentionable that already touched her deep inside, and her skin crawled.

Hedley came in with tea things on a tray and put them down beside her on a low table. ‘Leave the food,’ she told him. ‘Later, I think.’

‘Be a good chap,’ Emsworth said. ‘There’s a whisky decanter on the sideboard. Pour me a large one and one for Lady Helen.’

‘Will I need it?’

‘I think so.’