По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

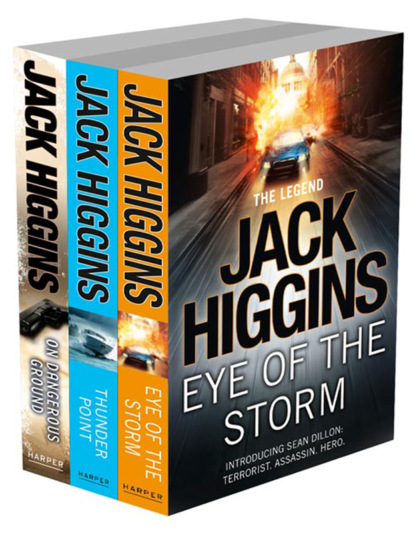

Sean Dillon 3-Book Collection 1: Eye of the Storm, Thunder Point, On Dangerous Ground

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Ferguson said, ‘What happened?’

Briefly, coldly, Brosnan told them. As he finished, a tall, greying man in surgeon’s robes came in. Brosnan turned to him quickly. ‘How is she, Henri?’ He said to the others, ‘Professor Henri Dubois, a colleague of mine at the Sorbonne.’

‘Not good, my friend,’ Dubois told him. ‘The injuries to the left leg and spine are bad enough, but even more worrying is the skull fracture. They’re just preparing her for surgery now. I’ll operate straight away.’

He went out. Hernu put an arm around Brosnan’s shoulders. ‘Let’s go and get some coffee, my friend. I think it’s going to be a long night.’

‘But I only drink tea,’ Brosnan said, his face bone white, his eyes dark. ‘Never could stomach coffee. Isn’t that the funniest thing you ever heard?’

There was a small café for visitors on the ground floor. Not many customers at that time of night. Savary had gone off to handle the police side of the business, the others sat at a table in the corner.

Ferguson said, ‘I know you’ve got other things on your mind, but is there anything you can tell us? Anything he said to you?’

‘Oh yes – plenty. He’s working for somebody and definitely not the IRA. He’s being paid for this one and from the way he boasted, it’s big money.’

‘Any idea who?’

‘When I suggested Saddam Hussein he got angry. My guess is you wouldn’t have to look much further. An interesting point. He knew about all of you.’

‘All of us?’ Hernu said. ‘You’re sure?’

‘Oh, yes, he boasted about that.’ He turned to Ferguson. ‘Even knew about you and Captain Tanner being in town to pump me for information, that’s how he put it. He said he had the right friends.’ He frowned, trying to remember the phrase exactly. ‘The kind of people who can access anything.’

‘Did he indeed?’ Ferguson glanced at Hernu. ‘Rather worrying, that.’

‘And you’ve got another problem. He spoke of the Thatcher affair as being just a try-out, that he had an alternative target.’

‘Go on,’ Ferguson said.

‘I managed to get him to lose his temper by needling him about what a botch-up the Valenton thing was. I think you’ll find he intends to have a crack at the British Prime Minister.’

Mary said, ‘Are you certain?’

‘Oh, yes.’ He nodded. ‘I baited him about that, told him he’d never get away with it. He lost his temper. Said he’d just have to prove me wrong.’

Ferguson looked at Hernu and sighed. ‘So now we know. I’d better go along to the Embassy and alert all our people in London.’

‘I’ll do the same here,’ Hernu said. ‘After all, he has to leave the country sometime. We’ll alert all airports and ferries. The usual thing, but discreetly, of course.’

They got up and Brosnan said, ‘You’re wasting your time. You won’t get him, not in any usual way. You don’t even know what you’re looking for.’

‘Perhaps, Martin,’ Ferguson said. ‘But we’ll just have to do our best, won’t we?’

Mary Tanner followed them to the door. ‘Look, if you don’t need me, Brigadier, I’d like to stay.’

‘Of course, my dear. I’ll see you later.’

She went to the counter and got two cups of tea. ‘The French are wonderful,’ she said. ‘They always think we’re crazy to want milk in our tea.’

‘Takes all sorts,’ he said and offered her a cigarette. ‘Ferguson told me how you got that scar.’

‘Souvenir of old Ireland,’ she shrugged.

He was desperately trying to think of something to say. ‘What about your family? Do they live in London?’

‘My father was a Professor of Surgery at Oxford. He died some time ago. Cancer. My mother’s still alive. Has an estate in Herefordshire.’

‘Brothers and sisters?’

‘I had one brother. Ten years older than me. He was shot dead in Belfast in nineteen-eighty. Sniper got him from the Divis Flats. He was a Marine Commando captain.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘A long time ago.’

‘It can’t make you particularly well disposed towards a man like me.’

‘Ferguson explained to me how you became involved with the IRA after Viet Nam.’

‘Just another bloody Yank sticking his nose in, is that what you think?’ he sighed. ‘It seemed the right thing to do at the time, it really did and don’t let’s pretend. I was up to my neck in it for five long and bloody years.’

‘And how do you see it now?’

‘Ireland?’ he laughed harshly. ‘The way I feel I’d see it sink into the sea with pleasure.’ He got up. ‘Come on, let’s stretch our legs,’ and he led the way out.

Dillon was in the kitchen in the barge heating the kettle when the phone rang. Makeev said, ‘She’s in the Hôpital St-Louis. We’ve had to be discreet in our enquiries, but from what my informant can ascertain, she’s on the critical list.’

‘Sod it,’ Dillon said. ‘If only she’d kept her hands to herself.’

‘This could cause a devil of a fuss. I’d better come and see you.’

‘I’ll be here.’

Dillon poured hot water into a basin then he went into the bathroom. First he took off his shirt, then he got a briefcase from the cupboard under the sink. It was exactly as Brosnan had forecast. Inside he had a range of passports, all of himself suitably disguised. There was also a first-class make-up kit.

Over the years he had travelled backwards and forwards to England many times, frequently through Jersey in the Channel Islands. Jersey was British soil. Once there, a British citizen didn’t need a passport for the flight to the English mainland. So, a French tourist holidaying in Jersey. He selected a passport in the name of Henri Jacaud, a car salesman from Rennes.

To go with it, he found a Jersey driving licence in the name of Peter Hilton with an address in the Island’s main town of St Helier. Jersey driving licences, unlike the usual British mainland variety, carry a photo. It was always useful to have positive identification on you, he’d learned that years ago. Nothing better than for people to be able to check the face with a photo and the photos on the driving licence and on the French passport were identical. That was the whole point.

He dissolved some black hair dye into the warm water and started to brush it into his fair hair. Amazing what a difference it made, just changing the hair colour. He blow-dried it and brilliantined it back in place, then he selected from a range in his case, a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles, slightly tinted. He closed his eyes, thinking about the role and when he opened them again, Henri Jacaud stared out of the mirror. It was quite extraordinary. He closed the case, put it back in the cupboard, pulled on his shirt and went into the stateroom carrying the passport and the driving licence.

At that precise moment Makeev came down the companionway. ‘Good God!’ he said. ‘For a moment I thought it was someone else.’

‘But it is,’ Dillon said. ‘Henri Jacaud, car salesman from Rennes on his way to Jersey for a winter break. Hydrofoil from St Malo.’ He held up the driving licence. ‘Who is also Jersey resident Peter Hilton, accountant in St Helier.’

‘You don’t need a passport to get to London?’

‘Not if you’re a Jersey resident, it’s British territory. The driving licence just puts a face to me. Always makes people feel happier. Makes them feel they know who you are, even the police.’