Soil Culture

In our article on manures, we have shown that it is the texture of soils, and their power to control moisture and heat, that renders them productive: hence, no soil can be poor that is stirred deep and kept in a friable condition, without being too open and porous; and no soil can be good that is hard and not retentive of moisture, without having water stand upon it. Hence, the great secret of successful farming, is, such a mixture of the soils, and of fertilizers with the soil, as shall keep it friable and moist, and such thorough drainage as will prevent water from standing so as to become stagnant, and to unduly chill the roots of growing plants. Nature has provided, near at hand, all that is essential to productiveness; all that is necessary is to properly mix them. We do not believe that there is an acre of land now under cultivation in the United States, in a latitude where corn will grow, on which we can not raise a hundred bushels of shelled Indian corn, without applying anything but what may be raised out of that soil, and procured in the shape of manure by animals in consuming that product. The poorest farm in America may be brought up to a state of great fertility, without applying one dollar's worth of any foreign substance. Plow deep, turn under all the green substances possible, and feed out the products on the farm and apply the manure, and mix opposite soils, that may be found in different localities. Three years will secure great productiveness, and the same course will increase its value, from year to year, without cost. Three things only are essential to convert poor land into the best; deep and thorough stirring and pulverization, suitable draining, and thorough mixture of soils of different qualities, and the incorporation of such animal and vegetable substances as can be produced on the land itself. We would not declare against foreign manures, but insist that the necessary ingredients are found, or may be manufactured near at hand. The philosophy of deep plowing and thorough pulverization is obvious. A fine soil will retain and appropriate moisture in an eminent degree, on the principle of capillary attraction, or as a sponge or a piece of loaf sugar will take up water. There is also room for excess of water to sink away from the surface, and return again when needed. It also affords room for the roots of plants. Such a soil also receives moisture from the atmosphere. The atmosphere also contains much water, and more in the heat of summer than at any other time. The air also, with a constant pressure of fifteen pounds to the square inch, enters to a considerable depth into the soil, and the deeper it is stirred, and the more thoroughly it is pulverized, the more it will enter. In coming in contact with the cool moisture below, it is condensed and waters the soil, on the principle that a pitcher of cold water in a warm room has large drops of water on the outside; that water is a mere condensation of moisture in the atmosphere. The cool subsoil acts in the same way upon the atmosphere at night. A deeply disintegrated soil, also, seldom washes by rain. Shallow-plowed and coarse land sends off the water after a slight rain, while deep-plowed and thoroughly pulverized land retains it. The philosophy of manures involves the same principles. All the fertilizers act upon soils in such a manner as to render them fine, and open an immense surface to the action of the atmosphere, and form large reservoirs for moisture through their innumerable fine pores. Draining is to carry off an excess of water that would stand on an unfavorable subsoil. That water, on undrained land, causes two evils; it stagnates and renders plants unhealthy, and it is too cool, rendering land what we call cold. Thus, the deeper you plow land, and the finer you make it, the warmer it will be, and the more perfectly it will control moisture. Mixing soils by subsoiling, trenching, and deep plowing, and by carting on foreign substances, is wholly on this principle. Sand that drifts about with the wind is too light to retain moisture, and needs clay carted on. By this means the poorest white sand has often been converted into the most productive soil. Definite rules for this mixture of soils can not be safely given. The rules must differ in different localities and circumstances; it must, therefore, be determined by experiment. Analyzing soils is sometimes of use, but usually has too much importance attached. We do not advise farmers to study it. Let them try applications and mixtures, at first on a small scale: they will soon learn what is best on their farms, and may then proceed without loss. Some lands are of such a character that the carting on, and suitably mixing, the substances in which they are deficient, may cost as much as it did to clear the land of its original forest; but it will pay well for a long series of years. So well are we persuaded of the utility and correctness of these brief hints, that, in selecting a farm, we should regard the location more than the quality of the soil. The latter we could mend easily; while we should find it difficult to move our farm to a more favorable location. Poor land near a city or large town, or on some great thoroughfare, we should much prefer to good land far removed from market, or in an unpleasant location.

SPINAGE, OR SPINACH

Both these names are correct; the former is the general one among Americans. This plant is used in soups, but more generally boiled alone and served as greens. In the spring of the year, this is one of the most wholesome vegetables. By sowing at different times, we may have it at any season of the year, but it is more tender and succulent in the spring. The male and female flowers are produced on separate plants. The male blossoms are in long, terminal spikes, and the female in clusters, close at the stalk, on each joint.

Varieties—The two best are the broad, or summer, and the prickly, or fall. There are three others—the English Patience Dock, the Holland, or Lamb's Quarter, and the New Zealand. The first two are sufficient. Sow in August and September for winter and spring use, and in spring for summer. Sow in rich soil, in drills eighteen inches apart. Thin to three inches in the row, and when large enough for use, remove every other one, leaving them six inches apart. To raise seed, have male plants at convenient distances, say one in two or three feet. When they have done blossoming, remove the male plants, giving all the room to the others, for perfecting the seed. Success depends upon very rich soil and plenty of moisture.

SQUASH

There are several varieties of both summer and winter squashes. All the summer varieties have a hard shell, when matured. They are usually eaten entire, outside, seeds and all, while young and tender, from one quarter to almost full grown. They are also used as a fall and winter squash, rejecting the shell and that portion of the inside which contains the seeds. The Summer Crookneck, and Summer Scolloped, both white and yellow, are the principal summer squashes. The finest is the White Scolloped. The best winter varieties are the Acorn, Valparaiso, Winter Crookneck, and Vegetable Marrow or Sweet Potato squash. The latter is the best known.

Cultivate as melons, but leave only two plants in a hill. They do best on new land. Varieties should be grown far apart, and far removed from pumpkins, as they mix very easily, and at a great distance. Bugs eat them worse than any other garden vegetable. The only sure remedy is the box covered with gauze or glass. As they are great runners, they do better with their ends clipped off. Used as a vegetable for the table, and in the same manner as pumpkins, for pies.

STRAWBERRY

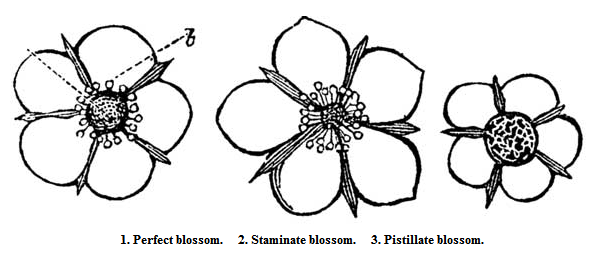

None of our small fruits are more esteemed, or more easily raised, and yet none more frequently fails. Failures always result from carelessness, or the want of a little knowledge of the best methods of cultivation. We omit much that might be said of the history and uses of the strawberry, and confine ourselves to a few brief directions, which, if strictly followed, will render every cultivator uniformly successful. No one need ever fail of growing a good crop of strawberries. In 1857, we saw plats of strawberries in Illinois, in the cultivation of which much money had been expended, and which were remarkably promising when in blossom, but which did not yield the cultivators five dollars' worth of fruit. In the language of the proprietors, "they blasted." Strawberries never blast; but, for the want of fertilizers at suitable distances, they may not fill. There are but three causes of failure—want of fertilizers, excessive drought, and allowing the vines to become too thick. Of most of our best varieties, the blossoms are of two kinds—pistillate and staminate, or male and female—and they are essential to each other. The pistillate plants bear the fruit, and the staminates are the fertilizers, without which the pistillates will be fruitless. There are three kinds of blossom—pistillate, staminate, and perfect, as seen in the cut.

The first (1) is perfect; that is, has both the stamens and pistils well developed: this will produce a fair crop of fruit, without the presence of any other variety. The second (2) has the stamens large, while the pistils (the apparently small green strawberry in the centre) are not sufficiently developed to produce fruit: such plants seldom bear more than a few imperfectly-formed berries. The third (3) has pistils in abundance, but is destitute of stamens, and hence, will not bear alone. The two latter are to be placed near each other, to render them productive; they may be readily distinguished when in blossom. It is always safe to cultivate the hermaphrodite plants; that is, those producing perfect blossoms; but the pistillates and staminates, in due proportions, produce the largest crops, and finer fruit.

Soil.—Much has been said against high fertilization with animal manures, and in favor of vegetable mould only. We feel entirely satisfied that the largest crops of strawberries are grown on land highly manured with common barnyard manure. To plant and manure a strawberry-bed, begin on one side, and dig a trench eighteen inches deep (from two to three feet is much better) and as wide; put six inches of common manure in the bottom; dig another trench as deep, and place the soil upon the manure in the first trench; fill the last with manure as the first, and so on over the whole plat. Manure the surface lightly with very fine manure and wood-ashes.

Transplanting is usually better in the month of August. If done at that season, and it be not too dry, the plants will get such a growth the same season as to produce quite a good crop of fruit the next season. Planted as early in the spring as it will do to stir the soil, they are more sure to grow and yield a very few berries the first season, and very abundantly the next. If you would cultivate in hills, put them two feet apart each way; if otherwise, two feet one way, and one foot the other. Cut off the roots to two or three inches in length, and remove all the dead leaves; dip them in mud, which is a great means of causing them to grow; and set them in fine mould, the crown one inch below the level of the soil around, and leave it in a slight basin, and water it, unless the weather be damp. Many plants are lost from not being set low enough to escape drought. The basin will hold water, and nearly every plant will grow; excessive water will destroy them. Set out three or four rows of pistillate plants, and then one of the staminates, or fertilizers. Some set them out in beds and allow them to cover the whole ground, and cultivate by spading up the bed in alternate sections of eighteen inches or two feet each year, turning under, in the spring, that portion that bore fruit the previous season—which has long been recommended by good authority. This was the lamented Downing's method. We think rows preferable for this reason. The young plants formed by the runners are less vigorous after the first; hence, the tendency is to deterioration by this mode of culture. And this method does not afford so good an opportunity for stirring the soil around the plants as planting in rows; this stirring the soil is a great means of protecting from drought, and securing the most vigorous growth. Deep subsoiling between the rows early in the spring, or after fruiting, is valuable; hence, we always advise to cultivate in hills two feet apart each way, and renew them after they have borne two, or at most three crops.

Hermaphrodites are best for cultivation in beds. Many strawberry-beds do well the first year of their bearing, but are almost useless afterward. The cultivator says they all run to vines. In such cases, they overlook the fact that the staminate plants grow altogether the fastest, because their strength goes to support foliage in the absence of fruit, while bearing vines require much of their strength to mature the fruit; hence, if they are allowed to run together the second, or at most the third year, the fertilizers will monopolize the ground and prevent fruiting. This is the greatest cause of failure of a crop, next to a want of both kinds of plants. This is the origin of fears of having land too rich. It is said it all runs to vines without fruit; this is because the wrong vines have intruded—the staminates have overcome the pistillates. We reject the whole theory of the luxuriance of the vines preventing the production of fruit. The larger the vines the more fruit, provided only the vines are bearers, and not too thick: hence this invariable rule—always have fertilizers within five feet, and never allow the two kinds to run together. Manures should be applied in August, well spaded in. Applying in the spring to increase the crop for that season, is like feeding chickens in the morning to fatten them for dinner—it is too late. Fertilizing in August is a good preparation for a large crop for the next season. Strawberry-vines, in all freezing climates, should be covered, late in the fall, with forest-leaves or straw, to protect from the severity of winter, and enrich the land by what can be dug into the soil in spring. Rotten wood, fine chips, sawdust, &c., are all good for a fall top-dressing. After well hoeing and weeding in spring, until blossom-buds appear, just before the blossoms open, cover the bed thoroughly with spent tanbark, sawdust, or fine straw. This will keep down weeds, preserve moisture in the soil, enrich the ground, and protect the fruit from injury by rains, and in part from worms and insects. This should never be omitted.

Varieties are numerous, and, from the ease with which they are raised from seed, will rapidly increase; it is so frequent to have blossoms fertilized by pollen from several different varieties. Some of the most marked varieties are known in different parts of the country by very different names; hence, we advise cultivators to select the best in their locality. Every valuable variety is soon scattered over the country. The following are good:—

Burr's New Pine.—Originated at Columbus, Ohio, in 1856. Hardy, vigorous, and quite productive; very early; tender for market, but superior for a private garden.

Western Queen.—Originated at Cleveland, Ohio, by Professor J. P. Kirtland, 1849. Very hardy and productive; larger than the Hudson or the Willey; good for market; bears carriage well.

Longworth's Prolific.—Origin, Cincinnati, 1848. Regular, sure, full bearer of large, delicious fruit; good for market; an independent bearer.

M'Avoy's Superior.—Cincinnati, 1848. Received one-hundred-dollar prize from the Cincinnati Horticultural Society in 1851. Exceedingly large; hardy; female or pistillate flowers; needs fertilizers, and then is one of the best ever grown; rather tender for carriage, though it is extensively sold in Western markets.

Jenney's Seedling.—Valuable for ripening late; fruit large and regular; very productive, 3,200 quarts having been gathered from three quarters of an acre.

Hovey's Seedling.—Elliott puts it in his second class; but we can not avoid the conviction that it is one of the best that ever has been raised. It is pistillate, but with fertilizers it yields immense crops, of very fine large fruit. Boston Pine is one of the best fertilizers for the Hovey Seedling.

Hudson Bay.—A hardy and late variety, highly esteemed.

Pyramidal Chilian.—Hermaphrodite, highly valued.

Crimson Cone.—An old variety, quite early, and something of a favorite in Eastern markets.

Peabody's New Hautbois.—Originated in Columbus, Georgia, by Charles A. Peabody. Said to bear more degrees of heat and cold than any other variety. Very vigorous, fruit of the largest size, very many of the berries measuring seven inches in circumference. Flesh firm, sweet, and of a delicious pine-apple flavor. Rich, deep crimson. It may be seen in full size in the patent office report on agriculture for 1856. If this new fruit sustains its recommendations, it will prove the best of all strawberries.

Downing describes over one hundred varieties. We repeat our recommendation to select the best you can find near home. The following rules will insure success:

1. Make the ground very rich.

2. Put fertilizers within five feet of each other, and never allow different kinds to run together.

3. Cover the ground two inches deep with tan-bark, sawdust, or fine straw, just before the blossoms open; tan-bark is best.

4. Never allow the vines to become very thick, but thin them out.

5. Water every day from the appearance of the blossoms until done gathering the fruit; this increases the crop largely, and, at the South, has continued the vines in bearing until November. Daily watering will prolong the bearing season greatly in all climates, and greatly increase the crop.

6. Protect in winter by a slight covering of forest-leaves, coarse straw, or cornstalks.

7. To get a late crop, keep the vines covered deep with straw. You can retard their maturity two weeks, and daily watering will prolong it for weeks.

8. Apply, twice in the fall and once in the spring, a solution of potash, one pound in two pails of water, or two pounds in a barrel of water in which stable-manure has been soaked.

9. The best general applications to the soil, in preparing the bed, are lime, charcoal, and wood-ashes—one part of lime to two of ashes and three of charcoal. The application of wood-ashes will render less dissolved potash necessary.

These nine rules, strictly observed, will render every cultivator successful in all climates and localities.

SUGAR

There have, until recently, been but two general sources of our supply of sugar—the sugar-cane of the South, and the sugar-maple of the North. Beet-sugar will not be extensively manufactured in this country. We now have added the Sorgho, or Chinese sugar-cane, and the Imphee, or African sugar-cane, adapted to the North and the South, flourishing wherever Indian corn will grow, and raised as easily and surely, and much in the same way. Of the methods of making sugar from the old sugar-cane of the South, we need give no account. It is not an article of general domestic manufacture. It is made on a large scale on plantations, and is in itself simple, and easily learned by the few who become sugar-planters.

The process of manufacturing sugar from the maple-tree is very simple and everywhere known. It is to be regretted that our sugar-maples are being so extensively destroyed, and that those we pretend to keep for sugar-orchards are so unmercifully hacked up, in the process of extracting the sap. To so tap the trees as to do them the least possible injury, is a matter of much importance. Whether it should be done by boring and plugging up with green maple-wood after the season is over, or be done by cutting a small gash with an axe and leaving open, has been a disputed point. Many prefer the axe, and think the tree will be less blackened in the wood, and will last longer, provided it be judiciously performed. Cut a small, smooth gash; one year tap the tree low, and another high, and on alternate sides; scatter the wounds, made from year to year, as much as possible. Another process of tapping is now most popular with all who have tried it. Bore into the tree half an inch, with a bit not larger than an inch, slanting slightly up, that standing sap or water may not blacken the wood. Make the spout out of hoop-iron one and a fourth inches wide; cut the iron, with a cold chisel, into pieces four inches long; grind one end sharp; lay the pieces over a semicircular groove in a stick of hard wood, and place an iron rod on it lengthwise over the groove—slight blows with a hammer will bend it. These can be driven into the bark, below the hole made by the bit. They need not extend to the wood, and hence make no wound at all. If the wound dries before the season is over, deepen it a little by boring again, or by taking out a small piece with a gouge. This process will injure the trees less than any other. The spouts will be cheaper than wooden ones, and may last twenty years. Always hang buckets on wrought nails, that may be drawn out. Buckets made of tin, to hold three or four gallons, need cost only about twenty-five cents each, and, with good care, may last twenty years. A crook in the wire of the rim will make a good place to hang upon the nail. A hole bored in the ear of other buckets will answer the same purpose. In all windy situations, the bucket must be near the end of the spout, or much will be lost by being blown over by the wind. Great care to keep all vessels used, clean and sweet, and not burn the sugar in finishing it, will enable any one to succeed in making good maple-sugar. The various forms in which it is put up, and the manner of draining, are familiar to all makers. It is only necessary to add, that there are few small farms on which the sugar-maple will grow, where there might not be raised two or three hundred maples, within fifteen or twenty years, that would add greatly to the beauty, comfort, and value of the farm. On the highway as shade-trees, or on the side of lots, they would be very ornamental and profitable, without doing injury. We can not too strongly recommend raising sugar-maples. Always cultivate trees that will bear fruit, yield sugar, or be good for timber.

Sorgho, or Chinese sugar-cane, is raised much as Indian corn—only, it will bear some ten or twelve stalks in a hill, instead of three or four. In all parts of our continent, it produces enormous crops of stalks. The trials thus far indicate, that the quantity of saccharine matter it contains is not quite equal to that of the common sugar-cane; but, with the necessary facilities for manufacturing, it makes quite as good sugar and as fine sirups as the other cane. Suitable machinery, that need not be expensive, owned by a neighborhood of farmers, may enable all Northern men, where other cane will not grow, to make their own sugar cheaper than to buy. But it will be made probably by large establishments as other sugar. We give no method of making it. The subject is so new, that every method of manufacture finds its way into all the newspapers, and what might appear the best to-day would be quite antiquated to-morrow. We have seen as fine sugars and sirups, of all the different grades, made from this new cane, as any others we have ever tasted. The question is settled that imphee and sorgho will make good sugar in abundance. A few years will place such sugars among the great staple products of the country.

SUMMER-SAVORY

This is a hardy annual, raised from seed on any good soil, with no care but keeping free from weeds. The seed is small, and may not vegetate well in dry, warm weather, without a little shade or regular watering. Its use for culinary and medicinal purposes is well known. Gather and dry when nearly ripe. Keep in paper bags, or pulverize and put in glass bottles. For the benefit of persons who keep those sprightly pets called fleas, we mention the fact that dry summer-savory leaves, put in the straw beds, will expel those insects.

SUNFLOWER

This large, hardy, annual plant would be considered very beautiful, were it not so common. Three quarts of clear, beautiful oil are expressed from a bushel of the seed, in the same way as linseed-oil. The seed, in small quantities, is good for fowls. It may be grown with less labor than corn.