Soil Culture

The varieties for general cultivation are few. The common black is one of the best. The common wild American red, native in all the Middle and Eastern states, is greatly improved by cultivation. As it is perfectly hardy, and a great and early bearer, it should have a place in every collection. The Franconia is a fine fruit, and, among those generally cultivated, occupies the first place. The yellow Antwerp is fine-flavored and good-sized, but too soft for a general market-berry. The same is true of the Fastollf. The red Antwerp is good, but quite inferior to the new red Antwerp, or Hudson River Antwerp. The Ohio Evergreen is a new variety, hardy, prolific, and a long bearer, fine fruit in considerable quantities having been picked on the 1st of November. On this account, it should be in every garden. There are two kinds of red raspberries brought to notice by Mr. Lewis P. Allen, of Black Rock, N. Y., that deserve extensive cultivation, if they warrant his recommendation. Mr. Allen says he has cultivated them for a number of years, and, with no winter protection, they have borne a large crop of excellent fruit every year, pronounced by dealers in Buffalo market superior to any other variety. Should these varieties prove equally good elsewhere, they deserve a place in every garden in the land.

RHUBARB

There are several varieties of rhubarb now in cultivation.

The Victoria, Mammoth, and Scotch Hybrid, all of which (if they be really distinct) are fine and large, under proper culture. There is much of the old inferior kind, which generally affords only small short leaves, and which is of no value, compared with the large varieties. The method of growing is very simple, and yet the value of the plant depends mainly on right cultivation.

Propagation is by seeds, or by dividing the roots. By seed is preferable. The idea that the largest kinds will not produce seed is incorrect. We raised four or five quarts of seed from a single plant of the largest variety, in one season. Young plants are suitable for transplanting after the first year's growth. They should be set three feet apart each way. The soil should be thoroughly enriched and trenched two feet deep, with plenty of well-rotted manure in the bottom, and mixed in all the soil. Plant the crowns two or three inches below the surface to allow stirring the ground in the spring, without injury. After this they will only want enriching with well-rotted manure in rather liberal quantities, worked in with a fork in the fall or spring. Covering up with manure in the fall is good. Those who raise the largest leaves, lay bare the crowns in spring, and with a sharp knife, remove all the smaller crown-buds. The leaves will be greatly reduced in number, but increased in size. We have often seen a single stem of a leaf that weighed a full pound.

The roots live many years. We know a single root, in St. Lawrence county, N. Y., from which we ate pies and tarts twenty-two years ago, and which is now so vigorous as to yield more than a supply for two families through the season. The only care it has ever had, has been liberal supplies of well-rotted manure. The seed stocks have generally been broken off. They should always be, unless you wish to raise seed, then save one or two of the strongest. New crowns come out on the sides, from year to year, until each plant will cover a considerable space. The one mentioned, as being twenty-two years old, has never been moved during the whole time. It is not the giant kind, but the leaves are large and long. Rhubarb has a better flavor and requires much less sugar, by blanching. This is best done by placing an old barrel, without a bottom, over the hill as it begins to grow. The leaves will grow long, with white tender stems. Use it when the leaves are half or full grown, as you please.

RICE

This, in its value to the world as an article of food, is next to Indian corn. It is the main article of diet for one third of the human race. It is produced only in certain parts of the world, and its cultivation is so simple and easy, and so much a department of agriculture by itself, that we omit directions for growing it. The ravages of the rice-weevil, so destructive to rice lying in bulk, are prevented by the application of common salt, at the rate of half a pound to the bushel.

ROCKS

We frequently find, on some of our best land, large boulders, very hard, and too large to be removed, with any team we can command, and which would be in the way, in any place to which we might remove them. The best way to get rid of them, when it can be afforded, is to burn or blast them into pieces small enough to be easily handled. When this can not be afforded, the best method is to make an excavation by the side of them, deep enough to let them sink below the reach of the plow, and allow them to fall in, being careful not to get caught by them.

ROLLER

This is quite as indispensable to good farming and gardening as any other tool. It serves a great variety of useful purposes. The first is to pulverize soils. No man can get a full crop on a soil not made fine on the surface, however rich that soil may be. It is often the case that land needs rolling two or three times before the last harrowing and sowing the seed. Another purpose is, on all light soils, to place the soil close around the seeds after they have been covered. When this is not done, seeds will vegetate very unevenly, and, in dry weather, some of them not at all. Another advantage of rolling a field-crop is the greater facility and economy with which it can be harvested. It makes a level, smooth surface, sinking small stones out of the way of the scythe or reaper. Rolling makes grass-seed catch, when sown with a spring-crop. All beds of small seeds—as onions, beets, carrots, parsnips, &c.—should be rolled after planting. It will so smooth the surface, that hoeing and cultivating can be done without injury to the plants. The rows are also much more easily seen while the plants are young. Any crop will grow better and larger by not being too much exposed to the action of the atmosphere on its roots. When the soil is coarse, part of the seeds and roots are greatly exposed to the action of the atmosphere, and this exposure is very irregular. The roller so crushes the lumps and fills up the openings in the soil as to cause the atmosphere to act regularly on the whole crop. Few farmers stop to think that the pressure of the atmosphere on their soils is fifteen pounds' weight on every square inch, and that, hence, the air must penetrate to a considerable depth into the soil; and where the soil is coarse, the air enters too freely, and acts too powerfully for the good of the plants. Rollers are made of wood, iron, or freestone. For most purposes, wood is best. A log made true and even, or, better, narrow plank nailed on cylindrical ends, are the usual forms. From eighteen inches to three feet in diameter is the better size. Iron or stone rollers, in sections, are best for pulverizing soil disposed to cake from being annually overflowed with water, or from other causes.

ROOT CROPS

It is important that American farmers learn to attach much greater importance to the culture of roots. The potato is the best of all roots for feeding; but, as the yield has become so light in most localities, and the demand for it for human food has so greatly increased, it will no longer be grown extensively as food for animals. Farmers must, therefore, turn their attention to beets, carrots, and parsnips. Reasonable tillage will produce one thousand bushels to the acre of beets and carrots, and two hundred more of parsnips. These roots, raw or cooked, are valuable for all domestic animals. A horse will do better on part oats and part carrots, or beets, than upon clear oats. For milch cows, young stock, and fattening cattle, and for sheep and fowls, they are highly valuable. With the facilities now enjoyed, they may be raised at a cheap rate. Plant scarlet short-top radish-seed in the rows, to shade the vegetating seed and young plants, and to mark the rows, to facilitate clearing and stirring the ground, while the plants are very young, and using the most approved root-cleaners, and the same amount of food can not be grown at the same price in any other crops.

SAFFRON

This is a well-known medicinal herb, as easily grown as a bean or sunflower. It is principally used in eruptive diseases, to induce moisture of the skin and keep the eruption out. Sow in any good soil, in rows eighteen inches apart, and keep clean of weeds. When in full bloom, the flowers are gathered and dried.

SAGE

This is a hardy garden-herb, easily grown. Its value for medicinal and culinary purposes is well known. It is propagated by seeds, or by dividing the roots. With suitable protection in winter, roots will live for a number of years, bearing seed after the first.

Varieties are, the red, the broad-leaved, the green, and the small-leaved green. The red is most used for culinary purposes, and the broad-leaved is most medicinal. All the varieties may be used for the same purposes. Any garden-soil, not decidedly wet, is suitable for sage. Raise new plants once in three or four years. Plants may be renovated, by certain culture and care, but it is better to grow new ones. Cut the leaves two or three times in the season, and dry quickly, and put away in paper bags; or, better, pulverize and cork up in glass bottles. This is the best method of preserving all herbs for domestic use.

SALSIFY, OR VEGETABLE OYSTER

This is a hardy biennial vegetable, resembling a small parsnip, and as easily grown. When properly cooked, its flavor resembles the oyster, whence its name. Sow and cultivate as parsnips or carrots. It is suitable for use from November to May. It is better for being allowed to remain in the ground until wanted for use, though it may be well kept, in moist sand in the cellar. Care is necessary in saving seed as it shells and blows away like thistle seed, as soon as ripe. It must be sown quite thick, on account of its proneness not to vegetate. It should be more extensively cultivated.

SCRAPING LAND

This is a process needed only on land that has not been under cultivation long enough to become level. All new land has many knolls of greater or less size. As soon as the roots are out sufficiently to allow it, the knolls should be plowed and leveled with a common scraper. Most farmers neglect it as injurious to the soil, and too expensive. But when we consider that rough land never gets well plowed, and that the gradual wearing away of the knolls will continue their unproductiveness for a number of years, it will be seen that the cheapest way is to plow and scrape the land level at once, and thoroughly manure the places from which the soil has been scraped.

SEEDS

The best of everything should be saved for seed. Peas, beans, corn, tomatoes, &c., should not be gathered promiscuously, finally preserving the last that matures, for seed. Leave some of the finest and earliest stocks, and from them save seed, not from the first or the last that matures, but from the earliest that grows large and fair. Save tomato-seed from those that grow largest, but near the root. Gather all seeds as soon as mature, as remaining exposed to the weather is unfavorable to vegetation. Dry in a warm place in the shade, but not too near a stove or fire. Keep in paper bags, hung in a dry airy place, beyond the reach of mice.

Trying the quality of seeds is important, as it may save loss and disappointment, from sowing seeds that will not vegetate. A little cotton wool or moss in a tumbler containing a little water, and placed in a warm room, will afford a good means of testing seeds. Seeds placed on that wool, will vegetate sooner than they would do in the soil. But a more speedy, and generally sure method, is by putting a few seeds on the top of a hot stove. If they are good they will crack like corn in parching; otherwise they will burn without noise, and with very little motion. The improvement or declension of fruits, grains, and vegetables, depend very materially upon the manner of gathering and preserving seeds. Gather promiscuously and late, and keep without care, and rapid declension will be the result. Gather the earliest and best, and plant only the very best of that saved, and constant improvement will be secured.

SHEEP

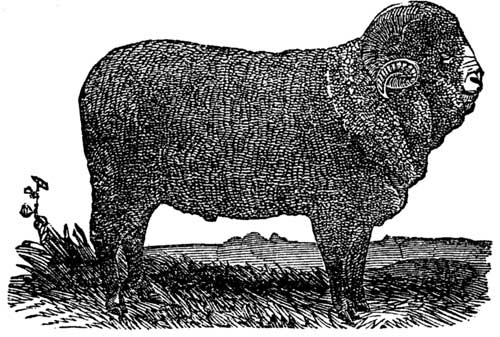

These are the most profitable of all domestic animals. The original cost is trifling, and the expense of raising and keeping is so light, and the sale of meat, tallow, hide, and wool, is so ready, that sheep-growing is always profitable. So important has this always been considered, that in all ages of the world, there have been shepherds, whose sole business it has been to tend their flocks. Were the flesh of sheep and lambs more extensively substituted for that of swine, in this country, it would be equally healthy and economical. American farmers do not attach to sheep-growing half the importance it deserves. We recommend a thorough study of the subject, in the use of the facilities afforded by the writings of practical men. We can only give the outlines of the subject in a work like this. A theory has been scientifically established by Peter A. Brown LL. D. of Philadelphia, in which it is shown that all sheep are divided into two species, Hair-bearing and Wool-bearing. These species crossed, produce sheep that bear both wool and hair, as the two never change. The hair makes blankets that will not shrink. The wool is good for making fulled cloth. Blankets made from the fleeces of sheep that are the product of the cross of these two species, will shrink in some places and not in others, just as the hair or wool prevails. It is also true that the hair-bearing sheep delight in low, moist situations and sea-breezes, while the wool-bearing sheep does best on high, airy, and dry land. These fleeces all pass as wool, but the microscope shows a marked and permanent difference, and one can easily learn to distinguish it at once, by the touch and with the naked eye. This is thrown out here to induce a thorough examination of the whole subject. There are three staples of wool, short, three inches long, middling, five inches, and long, eight inches. Varieties of sheep are numerous. We shall only mention a few. The question of the best breeds has been warmly controverted. We have no disposition to try to settle it. The question of the best variety must depend upon locality and design. If the wool is the object, then the Vermont Merino for the North, and the pure Saxony for the South, are evidently the best. If located near large cities, where the flesh is the main object, then the large-bodied, long-wooled breeds are much preferable. Among those much esteemed we note the following:—

The Cotswold mature young, and the flesh will vary in weight from fifteen to thirty pounds per quarter. The New Leicester is less hardy than the Cotswold, but heavier, weighing from twenty-four to thirty-six pounds per quarter. The Teeswater sheep, improved by a cross with the Leicester, is considered valuable. The Bampton is one of the very best grown in England. Fat ewes average twenty pounds per quarter, and wethers from thirty to thirty-five pounds. The Sussex, Hampshire, and Shropshire varieties of the Down sheep, are all highly esteemed. The Leicester are very valuable. An ordinary fleece weighs from three to five pounds. Mr. Joseph Beers of New Jersey had one that sheared thirteen pounds at one time, and the live weight of the sheep was 378 pounds.

There are French, Silesian, and Spanish Merinoes, much esteemed in Vermont and elsewhere. The average weight of a flock of ewes of French merinoes after shearing was 103 pounds. Their fleeces averaged twelve pounds and eight ounces. The fleece of one buck of the same flock weighed twenty pounds and twelve ounces.

The French Merino Ram.

The Silesian Merinoes are smaller, but produce beautiful fleeces. In a flock of nineteen ewes, the average weight of fleece was seven pounds and ten ounces, and that of the buck weighed ten and a half pounds.

A large flock of Spanish Merinoes yielded an average of a little over five pounds of well-washed wool. All these varieties are valuable for wool. The wool of the pure Saxony sheep, however, is best.

The Tartar sheep, called also Shanghae and Broadtail, is a recently-imported breed, of great promise for mutton. Their fleece is a fine silky hair, making fine blankets that will not shrink, but not good for fulled cloths. The ewes are remarkably prolific, producing sometimes five lambs at a time, and often twice a year. One ewe bore seven lambs in one year, all living and being healthy. The flesh is of the highest quality. This may stand at the head of all our sheep as a market animal. The cross of this with our common sheep has proved fine. They need to be further tested in this country. A new kind of sheep has also been imported from Africa, within a few years; a variety unknown to naturalists, but having some points in common with the Tartar sheep.

Diseases of Sheep.—There are several that have been very troublesome, but which experience has enabled us to cure. Scours is often very injurious. A little common soot from the chimney, or pulverized charcoal, is a sure remedy. Mix it with water, not so thick as to make it difficult to swallow, and give a teaspoonful every two hours, and relief will soon be experienced.

Water in the head is a disease caused by long exposure to wet and cold. This is prevented by a small blanket on the back of the sheep. The wool on the backs of sheep will be seen to be often parted, exposing the skin. Water falling on the back will penetrate the wool and run down, and wet and chill the whole body. A small cotton blanket, fifteen inches wide, and long enough to reach from the neck to the tail, fastened to its place by tying to the wool, and painted on the outside, will cause all the water to run off, saving the health of the sheep, and causing him to require less food. In the cold, wet season, every sheep should have such a blanket; they would cost three or four cents each, and be worth many times their cost in the saving of feed for the animals. The more comfortable an animal is, the less food will he require. Applying tar above the noses of sheep at shearing, that they may be compelled to smell it and eat a little for a long time, is considered favorable to their general health, and a preventive of rot.

The foot-rot, in cattle, sheep, and hogs, is a prevalent disease. Boys walking the path, barefoot, where such diseased animals frequently pass, may contract the disease. This is always cured by washing in blue vitriol. Most cases are cured by one application, and the most confirmed by two or three. Make a narrow passage, where only one animal can pass at once. Put in a trough twelve feet long, twelve inches wide, and as many deep. Put in that fifty pounds of blue vitriol and fill with water, throwing a little straw over the top. Cause the diseased animals to pass through that, and they will be cured. This is thought to be an invariable remedy. If sheep do not appear healthy on lowland pasture, give them small quantities of fine charcoal and salt, and they will be as healthy as on the hills. A little salt for sheep is useful during the whole year. The health of sheep is injured more in fall than at any other season; they are very apt to be neglected at the beginning of winter. They grow poor rapidly when their green feed first fails; a little hay and grain and a few roots then will keep them up, prevent disease, and make it less expensive to keep them through the winter. Feed in racks or troughs, when they can not get their food under foot, and as far as practicable, under shelter, and in a warm place. It is much cheaper, and keeps the sheep much more healthy. They should have fresh water, where they can drink, two or three times a day. Salt, mixed with wood-ashes and pulverized charcoal, should also be constantly within their reach. A few beets, carrots, or parsnips, are always valuable. Some green feed is very essential for ewes, for some time before the yeaning season. Corn is good for fattening sheep; but, for increasing the wool, it is not half as valuable as beans. Good bean-straw is better than hay. Corn-fodder is excellent. The product of one and a half acres of land, sowed with corn, will winter, in fine condition, one hundred sheep—the corn sowed the 20th of June, and cut up after it has begun to lose its weight slightly, and shocked up closely, bound round the top with straw, and then allowed to stand till wanted for feeding. To have healthy sheep, do not use a ram under two, or over six or seven years old, and raise no lambs from unhealthy ewes or rams. The expense of keeping sheep, as all other animals, is much less when they are kept warm. Much feed is wasted in keeping up animal heat, which would be saved by warm quarters.

Sheep-manure is better than any other, except that of fowls. No other parts with its qualities by exposure so slowly. Some farmers save all labor of carting and spreading sheep-manure, by having movable wire fences, and putting their sheep on one acre for a few days, and then removing to another. One hundred sheep may thus be made to manure an acre of land in ten days, better than any ordinary dressing of other manure. We should prefer carefully collecting and saving it under cover, mixed with muck or loam, and apply where and when we choose. Keeping a suitable number of sheep on a farm is very important in keeping up the farm. A farm devoted to grain or vegetables, without a suitable number of animals, usually runs down.

The time when lambs should be allowed to come is important. We much prefer letting them come when they please, if we have warm quarters, and can take a little extra care of them. This will give a larger growth, and furnish large lambs for market, at a season of the year when they are most desired, and bring the greatest price. For those who will not take the necessary pains, let them come when the weather has become warm and grass plenty. Sometimes a ewe loses her lamb, and you wish her to raise one of another ewe's, that has two. To make a ewe own another's lamb, take off the skin of her dead lamb, and bind it on to the other lamb, and she will smell it and own the lamb; after which the skin may be removed.

Sheep-culture is a subject to which farmers should give increased attention, until the average weight of sheep in the United States shall become one third greater than at present, and until there shall be ten sheep to one of all we have at present.

SHEPHERDIA OR BUFFALO BERRY

This is an ornamental shrub, growing from six to fifteen feet high, bearing a roundish red fruit, much esteemed for preserves. Trees are of two kinds, male and female, one bearing staminate and the other pistillate flowers. Hence no fruit can be grown without setting out the trees in pairs from six to fifteen feet apart. If you set out only two, and they chance to be of the same kind, you will get no fruit.

SOILS

The nature and management of soils must be measurably understood by any one who would be a thorough cultivator. The productive power of a soil depends much upon the character of the subsoil. A gravelly subsoil is, on the whole, the best. A thin soil lying on a cold clay subsoil—the hardpan of the East, and the crowfish clay of the West—however rich it may be, will be unproductive; while the same soil, on a gravelly subsoil, would produce abundantly. The best soils, for all purposes, are the brown or hazel-colored. Plowed in wet weather, they do not make mortar, and in dry weather they will not break in clods. Dark-mixed and russet moulds are considered the next best. The worst are the dark-gray or ash-colored. The deep-black alluvial soils of the Western prairies are an exception to all other soils, possessing, under proper treatment, great powers of production. Soils do not, to any considerable extent, afford food for plants. A willow-tree has been known to gain one hundred and fifty pounds' weight, without exhausting more than two or three ounces of the soil, and even that might have been wasted in drying and weighing.