Soil Culture

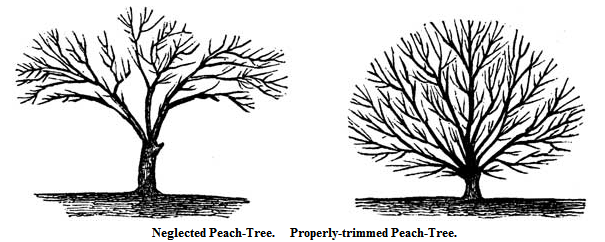

But a work to precede this annual shortening-in, is the original formation of a head to a peach-tree. Take a tree a year old from the bud, and cut it down to within two and a half feet from the ground. Below that numerous strong shoots will come out. Select three vigorous ones and let them grow as they please, carefully pinching off all the rest. In the fall you will have a tree of three good strong branches. In the next spring cut off these three branches, one half. Below these cuts, branches will start freely. Select one vigorous shoot to continue the limb, and another to form a new branch. Check the growth of the shoots below, by cutting off their ends, but do not rub them off, as they will form fruit branches. At the close of the season you will have a tree with six main branches, and some small ones for fruit, on the older wood. Repeat this process the third year, and you have a tree with twelve main branches, and plenty smaller ones for fruit. All these small branches on the old wood, should be shortened in half their length, to cause the leaf-buds near their base to start, so as to produce large numbers of young shoots. Continue this as long as you please, and make just as large a head and just such a form as you may wish, being careful only to control the shape of the top so as to let the sun and air freely into every part.

Trees thus trained may be planted thick enough to allow four hundred to stand on an acre, and will bear an abundance of the finest fruit, and all low enough to be easily picked. This method of training is much better than allowing the tree to shoot out on all sides from the ground: in that case, the branches are apt to split down and perish. This system of heading-in freely every year, preserves the life and health of the tree remarkably. Many of the finest peach-trees in France are from thirty to sixty years old, and some a hundred. We may, in this country, have peach-trees live fifty years, in the most healthy bearing condition. By trimming in this way, and carrying out fully this system, some have thrifty-looking peach-trees, more than a foot in diameter, bearing the very best of fruit. It is sheer neglect that causes our peach-orchards to perish after having borne from three to six years. Let every man who plants a peach-tree remember, that this system of training will make his tree live long, be healthy, grow vigorously, and bear abundantly.

Diseases of peach-trees have been a matter of much speculation. The result is, that the hope of the peach-grower is mainly in preventives.

The Yellows is usually regarded as a disease. Imagination has invented many causes of this evil. Some suppose it to be produced by small insects; others that it is in the seed. Again, it is ascribed to the atmosphere. It has been supposed to be propagated in many ways—by trimming a healthy tree with a knife that had been used on a diseased one; by contagion in the atmostphere, as the measles or small-pox; by impregnation from the pollen, through the agency of winds or bees; by the migration of small insects; or by planting diseased seeds, or budding from diseased trees. This great diversity of opinion leaves room to doubt whether the yellows in peach-trees be a disease at all, or only a symptom of general decay. The symptoms, as given in all the fruit-books, are only such as would be natural from decay and death of the tree, from any cause whatever. This may result from neglect to supply the soil with suitable manures, and to trim trees properly, and especially from over-bearing. This view of the case is more probable, from the fact that none pretend to have found a remedy. All advise to remove the tree thus affected at once, root and branch. We have seen the following treatment of such trees tried with marked success. Cut off a large share of the top, as when you would renew an old, neglected tree; lay the large roots bare, making a sort of basin around the body of the tree, and pour in three pailfuls of boiling water: the tree will start anew and do well. This is an excellent application to an old, failing peach-tree. The sure preventive of the yellows is, planting seeds of healthy trees, budding from the most vigorous, heading-in well, supplying appropriate manures, and general good cultivation.

Curled Leaves is another evil among peach-trees, occurring before the leaves are fully grown, and causing them to fall off after two or three weeks. Other leaves will put out, but the fruit is destroyed, and the general health of the tree injured. Elliott says the curl of the leaf is produced by the punctures of small insects. One kind of curled leaf is, but not this. But we have no doubt that Barry's theory is the correct one, viz., that it is the effect of sudden changes of the weather. We have noticed the curled leaf in orchards where the trees were so close together as to guard each other. On the side where the cold wind struck them, we noticed they were badly affected; while on the warm side, and in the centre where they were protected by the others, they exhibited very few signs of the curl. In western New York, unusual cold east winds always produce the curled leaves, on trees much exposed: hence, the only remedy is the best protection you can give, by location, &c.

Mildew is a minute fungus growing on the ends of tender shoots of certain varieties, checking their growth, and producing other bad effects. Syringe the trees with a weak solution of nitre, one ounce in a gallon of water, which will destroy the fungus and invigorate the tree.

The Borer has been the great enemy of the peach-tree, since about the close of the last century. The female insect, that produces the worms, deposites her eggs under rough bark, near the surface of the ground. This is done mostly in July, but occasionally from June to October. The eggs are laid in small punctures, and covered with a greenish glue; in a few days they come out, a small white worm, and eat through the bark where it is tender, just at, or a little below, the surface of the ground; they eat under the bark, between that and the wood, and, consuming a little of each, they frequently girdle the tree; as they grow larger, they perforate the solid wood; when about a year old, they make a cocoon just below the surface of the ground, change into a chrysalis state, and shortly come out a winged insect, to deposite fresh eggs. But the practical part of all this is the remedy: keep the ground clean around the trees, and rub off frequently all the rough bark; place around each tree half a peck of air-slaked lime, and the borer will not attack it. This should be placed there on the first of May, and be spread over the ground on the first of October; refuse tobacco-stems, from the cigar-makers, or any other offensive substance, as hen-manure, salt and ashes, &c., will answer the same purpose. We should recommend the annual cultivation of a small piece of ground in tobacco, for use around peach-trees. We have found it very successful against the borer, and it is an excellent manure; applied two or three times during the season, it proves a perfect remedy, and is in no way injurious, as an excessive quantity of lime might be.

Leaf Insects.—There are several varieties, which cause the leaves to curl and prematurely fall. This kind of curled leaf differs from the one described as the result of sudden changes and cold wind; that appears general wherever the cold wind strikes the tree, while this only affects a few leaves occasionally, and those surrounded by healthy leaves. The remedy is to syringe them with offensive mixtures, as tobacco-juice, or sprinkle them when wet with fine, air-slaked lime.

Varieties.—Their name is legion, and they are rapidly increasing, and their synonyms multiplying. A singular fact, in most of our fruit-books, is a minute description of useless kinds, and such descriptions of those that they call good, as not one in ten thousand cultivators will ever try to master—they are worse than useless, except to an occasional amateur cultivator.

Elliott, in his fruit-book, divides peaches into three classes: the first is for general cultivation; under this class he describes thirty-one varieties, with ninety-eight synonyms. His second class is for amateur cultivators, and includes sixty-nine varieties, with eighty-four synonyms. His third class, which he says are unworthy of further cultivation, describes fifty-four varieties, with seventy-seven synonyms. Cole gives sixty-five varieties, minutely described, and many of them pronounced worthless. In Hooker's Western Fruit-Book, we have some eighty varieties, only a few of which are regarded worthy of cultivation. Downing gives us one hundred and thirty-three varieties, with about four hundred synonyms. In all these works the descriptions are minute. The varieties of serrated leaves, the glandless, and some having globose glands on the leaves, and others with reniform glands. Then we have the color of the fruit in the shade and in the sun, which will, of course, vary with every degree of sun or shade. We submit the opinion that those books would have possessed much more value, had they only described the best mode of cultivating peaches, without having mentioned a single variety, thus leaving each cultivator to select the best he could find. Had they given a plain description of ten, or certainly of not more than fifteen varieties, those books would have been far more valuable for the people. We give a small list, including all we think it best to cultivate. Perhaps confining our selection to half a dozen varieties would be a further improvement:—

1. The first of all peaches is Crawford's Early. This is an early, sure, and great bearer, of the most beautiful, large fruit;—a good-flavored, juicy peach, though not the very richest. It is, on the whole, the very best peach in all parts of the country. Time, from July 15th to September 1st. Freestone.

2. Crawford's Late is very large and handsome; uniformly productive, though not nearly so good a bearer as Crawford's Early. Ripens last of September and in October. Fair quality, and always handsome; freestone; excellent for market.

3. Columbia.—Origin, New Jersey. It is a thoroughly-tested variety, raised and described by Mr. Cox, who wrote one of the earliest and best American fruit-books. Fine specimens were exhibited in 1856, grown in Covington, Ky. Excellent in all parts of the United States. Freestone.

4. George the Fourth.—A large, delicious, freestone peach, an American seedling from Mr. Gill, Broad street, New York. The National Pomological Society have decided the tree to be so healthy and productive as to adapt it to all localities in this country. It has twenty-five synonyms.

5. Early York.—Freestone; the best, and first really good, early peach. Time July at Cincinnati, and August at Cleveland. Time of ripening of all varieties varies with latitude, location, and season.

6. Grass Mignonne.—A foreign variety, a great favorite in France, in the time of Louis XIV. Very rich freestone, flourishing in all climates from Boston south. The high repute in which it has long been held is seen in its thirty synonyms. One of the best, when you can obtain the genuine. Time, August.

7. Honest John.—A large, beautiful, delicious, freestone variety. Highly prized as a late peach, maturing from the middle to the last of October. Indispensable in even a small selection.

8. Malacatune.—A very popular American freestone peach, derived from a Spanish, and is the parent of the Crawford peaches, both early and late.

9. Morris White.—Everywhere well known; a good bearer; best for preserving at the North; a good dessert peach South.

10. Morris Red Rare-ripe.—A favorite, freestone, July peach. The tree is healthy and a great bearer.

11. Old Mixon.—Should be found in all gardens and orchards; it is of excellent quality and ripens at a time when few good peaches are to be had; it endures spring-frosts better than any other variety; profitable.

12. Old Mixon Cling.—One of the most delicious early clingstones. Deserves a place in all gardens.

13. Monstrous Cling.—Not the best quality, but profitable for market on account of its great size.

14. Heath Cling.—Very good South and West. Wrapped in paper and laid in a cool room, it will keep longer than any other variety. Tree hardy and often produces when others fail. Excellent for preserving, and when quite ripe, is superior as a dessert fruit.

15. Blood Cling.—A well-known peach, excellent for pickling and preserving. It sometimes measures twelve inches in circumference. The old French Blood Cling is smaller. Many of these varieties will be found under other names. You will have to depend upon your nursery-man to give you the best he has, and be careful to bud from any choice variety you may happen to taste. Difficulties and disappointments will always attend efforts to get desired varieties.

PEAR

The pear is a native of Europe and Asia, and, in its natural state, is quite as unfit for the table as the crab-apple. Cultivation has given it a degree of excellence that places it in the first rank among dessert-fruits. No other American fruit commands so high a price. New varieties are obtained by seedlings, and are propagated by grafting and budding: the latter is generally preferred. Root-grafting of pears is to be avoided; the trees will be less vigorous and healthy. The difficulty of raising pear-seedlings has induced an extensive use of suckers, to the great injury of pear-culture. Fruit-growers are nearly unanimous in discarding suckers as stocks for grafting. The difficulty in raising seedling pear-trees is the failure of the seeds to vegetate. A remedy for this is, never to allow the seeds to become dry, after being taken from the fruit, until they are planted. Keep them in moist sand until time to plant them in the spring, or plant as soon as taken from the fruit. The spring is the best time for planting, as the ground can be put in better condition, rendering after-culture much more easy. The pear will succeed well on any good soil, well supplied with suitable fertilizers. The best manures for the pear are, lime in small quantities, wood-ashes, bones, potash dissolved, and applied in rotten wood, leaves, and muck, with a little stable-manure and iron-filings—iron is very essential in the soil for the pear-tree. In all soils moderately supplied with these articles, all pear-trees grafted on seedling-stocks, and those that flourish on the foreign quince, will do well. A good yellow loam is most natural; light sandy or gravelly land is unfavorable. It is better to cart two or three loads of suitable soil for each tree on such land. The practice of budding or grafting on apple-stocks, on crab-apples, and on the mountain-ash, should be utterly discarded. For producing early fruit, quince-stocks and root-pruning are recommended.

Setting out pear-trees properly is of very great importance. The requisites are, to have the ground in good condition, from manure on the crop of the last season, and thoroughly subsoiled and drained. Pear-trees delight in rather heavy land, if it be well drained; but water, standing in the soil about them, is utterly ruinous. Pear-trees, well transplanted on moderately rich land, well subsoiled and well drained, will almost always succeed. By observing the following brief directions, any cultivator may have just such shaped tops on his pear-trees as he desires. Cut short any shoots that are too vigorous, that those around them may get their share of the sap, and thus be enabled to make a proportionate growth. After trees have come into bearing, symmetry in the form of their heads may be promoted by pinching off all the fruit on the weak branches, and allowing all on the strong ones to mature.

Those two simple methods, removing the fruit from too vigorous shoots, and cutting in others, half or two-thirds their length, will enable one to form just such heads as he pleases, and will prove the best preventives of diseases.

Diseases.—There are many insects that infest pear-orchards, in the same manner as they do apples, and are to be destroyed in the same way. The slugs on the leaves are often quite annoying. These are worms, nearly half an inch long, olive-colored, and tapering from head to tail, like a tadpole. Ashes or quicklime, sprinkled over the leaves when they are wet with dew or rain, is an effectual remedy.

Insect-Blight.—This has been confounded with the frozen-sap blight, though they are very different. In early summer, when the shoots are in most vigorous growth, you will notice that the leaves on the ends of branches turn brown, and very soon die and become black. This is caused by a worm from an egg, deposited just behind or below a bud, by an insect. The egg hatches, and the worm perforates the bark into the wood, and commits his depredations there, preventing the healthy flow of the sap, which kills the twig above. Soon after the shoot dies, the worm comes out in the form of a winged insect, and seeks a location to deposite its eggs, preparatory to new depredations. The remedy is to cut off the shoots affected at once, and burn them. The insect-blight does not affect the tree far below the location of the worm. Watch your trees closely, and cut off all affected parts as soon as they appear, and burn them immediately, and you will soon destroy all the insects. But very soon after the appearance of the blight they leave the limb; hence a little delay will render your efforts useless. These insects often commit the same depredations on apple and quince-trees. We had an orchard in Ohio seriously affected by them. We know no remedy but destruction as above.

The Frozen-Sap Blight is a much more serious difficulty. Its nature and origin are now pretty well settled. In every tree there are two currents of sap: one passes up through the outer wood, to be digested by the leaves; the other passing down in the inner bark, deposites new wood, to increase the size of the tree. Now, in a late growth of this kind of wood, the process is rapidly going on, at the approach of cold weather, and the descending sap is suddenly frozen, in this tender bark and growing wood. This sudden freezing poisons the sap, and renders the tree diseased. The blight will show itself, in its worst form, in the most rapid growing season of early summer, though the disease commenced with the severe frosts of the previous autumn. Its presence may be known by a thick, clammy sap, that will exude in winter or spring pruning, and in the discoloration of the inner bark and peth of the branches. On limbs badly affected on one side, the bark will turn black and shrivel up. But its effects in the death of the branches only occur when the growth of the tree demands the rapid descent of the sap: then the poisoned sap which was arrested the previous fall, in its downward passage, is diluted and sent through the tree; and when it is abundant, the whole tree is poisoned and destroyed in a few days; in others more slightly affected, it only destroys a limb or a small portion of the top. Another effect of this fall-freezing of sap and growing wood, is to rupture the sap-vessels, and thus prevent the inner bark from performing its functions. This theory is so well established, that an intelligent observer can predict, in the fall, a blight-season the following summer. If the summer be cool, and the fall warm and damp, closed by sudden cold, the blight will be troublesome the next season, because the plentiful downward flow of sap, and rapid growth of wood, were arrested by sudden freezing. If the summer is favorable, and the wood matures well before cold weather, the blight will not appear. This is of the utmost practical moment to the pear-culturist. Anything in soil, situation, or pruning, that favors early maturity of wood, will serve as a preventive of blight; hence, cool, moist situations are not favorable in climates subject to sudden and severe cold weather in autumn. Root-pruning and heading-in, which always induce early maturity of wood, are of vast importance; they will, almost always, prevent frozen-sap blight. If, in spite of you, your pear-trees will make a late luxuriant growth, cut off one half of the most vigorous shoots before hard freezing, and you will check the flow of sap, by removing the leaves and shoots that control it, and save your trees. If blight makes its appearance, cut off at once all the parts affected. The effects will be visible in the wood and inner bark, far below the external apparent injury. Remove the whole injured part, or it will poison the rest of the tree. When this frozen sap is extensive, it poisons and destroys the whole tree; when slight, the tree often wholly recovers. If a spot of black, shrivelled bark appears, shave it off, deep enough to remove the affected parts, and cover the wound with grafting-wax. Remove all affected limbs. These are the only remedies. But the practice of pruning both roots and branches will prove a certain preventive. A tree growing in grass, where it grows more slowly, and matures earlier in the season, will escape this blight; while one growing in very rich garden soil, and continuing to grow until cold weather, will suffer severely. The effects on orchards, in different soils and localities everywhere, confirm this theory. A little care then will prevent this evil, which has sometimes been so great as to discourage attempts at raising pears. In some localities, some of the finer varieties of pears, as the virgalieu, are ruined by cracking on the trees before ripening. Applications of ashes, salt, charcoal, iron-filings, and clay on light lands, will remedy this evil.

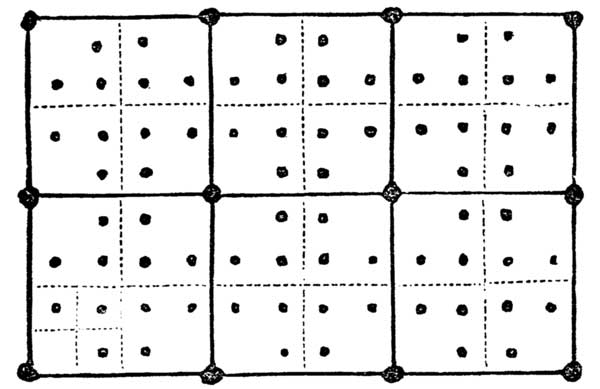

Distances apart.—All fruit-trees had better occupy as little ground as is consistent with a healthy vigorous growth. They are manured and well cultivated, at a much less expense. The trees protect each other against inclement weather. The fruit is more easily harvested. And it is a great saving of land, as nothing else can be profitably grown in an orchard of large fruit-trees. The two kinds of pear-trees, dwarf and standard, may be planted together closely and be profitable for early and abundant bearing. The plan given on the next page of a pear-orchard, recommended in Cole's Fruit Book, is the best we have seen.

In the plan the trees on pear-stocks, designed for standards, occupy the large black spots where the lines intersect. They are thirty-three feet apart. The small spots indicate the position of dwarf-trees on quince stocks. Of these there are three on each square rod. An acre then would have forty standard trees, and four hundred and eighty dwarfs. The latter will come into early bearing, and be profitable, long before the former will produce any fruit. This will induce and repay thorough cultivation. They should be headed in, and finally removed, as the standards need more room. One acre carefully cultivated in this way, will afford an income sufficient for the support of a small family.

Plan of a Pear-Orchard.

Gathering and Preserving.—Most fruits are better when allowed fully to ripen on the tree. But with pears, the reverse is true; most of them need to be ripened in the house, and some of them, as much as possible, excluded from the light. Gather when matured, and when a few of the wormy full-grown ones begin to fall, but while they adhere somewhat firmly to the tree. Barrel or box them tight, or put them in drawers in a cool dry place. About the time for them to become soft, put them in a room, with a temperature comfortable for a sitting-room, and you will soon have them in their greatest perfection. They do better in a warm room, wrapped in paper or cotton. A few only ripen well on the trees. Those ripened in the house keep much longer and better.

Varieties.—The London Horticultural Society have proved seven hundred varieties, from different parts of the world, in their experimental garden. Cole speaks of eight hundred and Elliott of twelve hundred varieties. There are now probably more than three thousand growing in this country. Many seedlings, not known beyond the neighborhood where they originated, may be among our very best. From six to ten varieties are all that need be cultivated. We present the following list, advising cultivators to select five or six to suit their own tastes and circumstances, and cultivate no more. We do not give the usual descriptions of the varieties selected. The mass of cultivators, for whom this work is specially intended, will never learn and test the descriptions. They will depend upon their nursery-man, and bud and graft from those they have tasted.