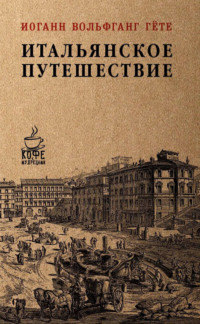

Letters from Switzerland and Travels in Italy

Sicily – Messina

In seeking out and visiting these spots we were accompanied by a friendly consul, who spontaneously put himself to much trouble on our account – a kindness to be gratefully acknowledged in this wilderness more than in any other place. At the same time, having learned that we were soon about to leave, he informed us that a French merchantman was on the point of sailing for Naples. The news was doubly welcome, as the flag of France is a protection against the pirates.

We made our kind cicerone aware of our desire to examine the inside of one of the larger (though still one storied) huts, and to see their plain and extemporized economy. Just at this moment we were joined by an agreeable person, who presently described himself to be a teacher of French. After finishing our walk, the consul made known to him our wish to look at one of these buildings, and requested him to take us home with him and show us his.

We entered the hut, of which the sides and roof consisted alike of planks. The impression it left on the eye was exactly that of one of the booths in a fair, where wild beasts or other curiosities are exhibited. The timber work of the walls and the roof was quite open. A green curtain divided off the front room, which was not covered with deals, but the natural floor was left just as in a tent. There were some chairs and a table; but no other article of domestic furniture. The space was lighted from above by the openings which had been accidentally left in the roofing. We stood talking together for some time, while I contemplated the green curtain and the roof within, which was visible over it, when all of a sudden from the other side of the curtain two lovely girls' heads, black-eyed, and black-haired, peeped over full of curiosity, but vanished again as soon as they saw they were perceived. However, upon being asked for by the consul, after the lapse of just so much time as was necessary to adorn themselves, they came forward, and with their well dressed and neat little bodies crept before the green tapestry. From their questions we clearly perceived that they looked upon us as fabulous beings from another world, in which most amiable delusion our answers must have gone far to confirm them. The consul gave a merry description of our singular appearance: the conversation was so very agreeable, that we found it hard to part with them. It was not until we had got out of the door that it occurred to us that we had never seen the inner room, and had forgotten all about the construction of the house, being entirely taken up with its fair inhabitants.

Messina, Saturday, May 12, 1787.

Among other things we were told by the consul, that although it was not indispensably necessary, still it would be as well to pay our respects to the governor, a strange old man, who, by his humours and prejudices, might as readily injure as benefit us: that besides it always told in his (the consul's) favour if he was the means of introducing distinguished personages to the governor; and besides, no stranger arriving here can tell whether some time or other he may not somehow or other require the assistance of this personage. So to please my friend, I went with him.

As we entered the ante-chamber, we heard in the inner room a most horrible hubbub; a footman, with a very punch-like expression of countenance, whispered in the consul's ear: – "An ill day – a dangerous moment!" However we entered, and found the governor, a very old man, sitting at a table near the window, with his back turned towards us. Large piles of old discoloured letters were lying before him, from which, with the greatest sedateness, he went on cutting out the unwritten portion of the paper – thus giving pretty strong proofs of his love of economy. During this peaceful occupation, however, he was fearfully rating and cursing away at a respectable looking personage, who, to judge from his costume, was probably connected with Malta, and who, with great coolness and precision of manner, was defending himself, for which, however, he was afforded but little opportunity. Though thus rated and scolded, he yet with great self-possession endeavoured by appealing to his passport and to his well-known connections in Naples, to remove a suspicion which the governor, as it would appear, had formed against him as coming backwards and forwards without any apparent business. All this, however, was of no use: the governor went on cutting his old letters, and carefully separating the clean paper, and scolding all the while.

Sicily – Messina

Besides ourselves there were about twelve other persons in the room, spectators of the bull-baiting, standing hovering in a very wide circle, and apparently envying us our proximity to the door, as a desirable position should the passionate old man seize his crutch, and strike away right and left. During this scene our good consul's face had lengthened considerably; for my part, my courage was kept up by the grimaces of a footman, who, though just outside the door, was close to me, and who, as often as I turned round, made the drollest gestures possible to appease my alarm, by indicating that all this did not matter much.

And indeed the awful affair was quickly brought to an end. The old man suddenly closed it with observing that there was nothing to prevent him clapping the Maltese in prison, and letting him cool his heels in a cell – however, he would pass it over this time; he might stay in Messina the few days he had spoken of – but after that he must pack off, and never show his face there again. Very coolly, and without the slightest change of countenance, the object of suspicion took his leave, gracefully saluting the assembly, and ourselves in particular, as he passed through the crowd to get to the door. As the governor turned round fiercely, intending to add yet another menace, he caught sight of us, and immediately recovering himself, nodded to the consul, upon which he stepped forward to introduce me.

The governor was a person of very great age; his head bent forwards on his chest, while from beneath his grey shaggy brows, black sunken eyes cast forth stealthy glances. Now, however, he was quite a different personage, from what we had seen a few moments before. He begged me to be seated; and still uninterruptedly pursuing his occupation, asked me many questions, which I duly answered, and concluded by inviting me to dine with him as long as I should remain here. The consul, satisfied as well as myself, nay, even more satisfied, since he knew better than I did the danger we had escaped, made haste to descend the stairs; and, for my part, I had no desire ever again to approach the lion's den.

Messina, Sunday, May 13, 1787.

Waking this morning, we found ourselves in a much pleasanter apartment, and with the sun shining brightly, but still in poor afflicted Messina. Singularly unpleasant is the view of the so-called Palazzata, a crescent-shaped row of real palaces, which for nearly a quarter of a league encloses and marks out the roadstead. All were built of stone, and four stories high; of several the whole front, up to the cornice of the roof, is still standing, while others have been thrown down as low as the first, or second, or third story. So that this once splendid line of buildings exhibits at present with its many chasms and perforations, a strangely revolting appearance: for the blue heaven may be seen through almost every window. The interior apartments in all are utterly destined and fallen.

One cause of this singular phenomenon is the fact that the splendid architectural edifices erected by the rich, tempted their less wealthy neighbours to vie with them, in appearance at least, and to hide behind a new front of cut stone the old houses, which had been built of larger and smaller rubble-stones, kneaded together and consolidated with plenty of mortar. This joining, not much to be trusted at any time, was quickly loosened and dissolved by the terrible earthquake. The whole fell together. Among the many singular instances of wonderful preservation which occurred in this calamity, they tell the following. The owner of one of these houses had, exactly at the awful moment, entered the recess of a window, while the whole house fell together behind him; and there, suspended aloft, but safe, he calmly awaited the moment of his liberation from his airy prison. That this style of building, which was adopted in consequence of having no quarries in the neighbourhood, was the principal cause why the ruin of the city was so total as it was, is proved by the fact that the houses which were of a more solid masonry are still standing. The Jesuits' College and Church, which are solidly built of cut stone, are still standing uninjured, with their original substantial fabric unimpaired. But whatever may be the cause, the appearance of Messina is most oppressive, and reminds one of the times when the Sicani and Siculi abandoned this restless and treacherous district, to occupy the western coast of the island.

After passing the morning in viewing these ruins, we entered our inn to take a frugal meal, We were still sitting at table, feeling ourselves quite comfortable, when the consul's servant rushed breathless into the room, declaring that the governor had been looking for me all over the city – he had invited me to dinner, and yet I was absent. The consul earnestly intreated me to go immediately, whether I had or not dined – whether I had allowed the hour to pass through forgetfulness or design. I now felt, for the first time, how childish and silly it was to allow my joy at my first escape to banish all further recollection of the Cyclop's invitation. The servant did not allow me to loiter; his representations were most urgent and most direct to the point; if I did not go the consul would be in danger of suffering all that this fiery despot might chose to inflict upon him and his countrymen.

Messina – The Palazzata

Whilst I was arranging my hair and dress, I took courage, and with a lighter heart followed, invoking Ulysses as my patron saint, and begging him to intercede in my behalf with Pallas Athène.

Arrived at the lion's den, I was conducted by a fine footman into a large dining-room, where about forty people were sitting at an oval table, without, however, a word being spoken. The place on the governor's right was unoccupied, and to it was I accordingly conducted.

Having saluted the host and his guests with a low bow, I took my seat by his side, excused my delay by the vast size of the city, and by the mistakes which the unusual way of reckoning the time had so often caused me to make. With a fiery look, he replied, that if a person visited foreign countries, he ought to make a point to learn its customs, and to guide his movements accordingly. To this I answered that such was invariably my endeavour, only I had found that, in a strange locality, and amidst totally new circumstances, one invariably fell at first, even with the very best intentions, into errors which might appear unpardonable, but for the kindness which readily accepted in excuse for them the plea of the fatigue of travelling, the distraction of new objects, the necessity of providing for one's bodily comforts, and, indeed, of preparing for one's further travels.

Hereupon he asked me how long I thought of remaining. I answered that I should like, if it were possible, to stay here for a considerable period, in order to have the opportunity of attesting, by my close attention to his orders and commands, my gratitude for the favour he had shewn me. After a pause he inquired what I had seen in Messina? I detailed to him my morning's occupation, with some remarks on what I had seen, adding that what most had struck me was the cleanliness and good order in the streets of this devastated city. And, in fact, it was highly admirable to observe how all the streets had been cleared by throwing the rubbish among the fallen fortifications, and by piling up the stones against the houses, by which means the middle of the streets had been made perfectly free and open for trade and traffic. And this gave me an opportunity to pay a well-deserved compliment to his excellency, by observing that all the Messinese thankfully acknowledged that they owed this convenience entirely to his care and forethought. "They acknowledge it, do they," he growled: "well, every one at first complained loudly enough of the hardship of being compelled to take his share of the necessary labour." I made some general remarks upon the wise intentions and lofty designs of government being only slowly understood and appreciated and on similar topics. He asked if I had seen the Church of the Jesuits, and when I said, No, he rejoined that he would cause it to be shown to me in all its splendour.

During this conversation, which was interrupted with a few pauses, the rest of the company, I observed, maintained a deep silence, scarcely moving except so far as was absolutely necessary in order to place the food in their mouths. And so, too, when the table was removed, and coffee was served, they stood up round the walls like so many wax dolls. I went up to the chaplain, who was to shew me the church, and began to thank him in advance for the trouble. However, he moved off, after humbly assuring me that the command of his excellency was in his eyes all sufficient. Upon this I turned to a young stranger who stood near, who, however, Frenchman as he was, did not seem to be at all at his ease; for he, too, seemed to be struck dumb and petrified, like the rest of the company, among whom I recognized many faces who had been anything but willing witnesses of yesterday's scene.

Messina – The Governor

The governor moved to a distance; and after a little while, the chaplain observed to me that it was time to be going. I followed him; the rest of the company had silently one by one disappeared. He led me to the gate of the Jesuit's church, which rises in the air with all the splendour and really imposing effect of the architecture of these fathers. A porter came immediately towards us, and invited us to enter; but the priest held me back, observing that we must wait for the governor. The latter presently arrived in his carriage, and, stopping in the piazza, not far from the church, nodded to us to approach, whereupon all three advanced towards him. He gave the porter to understand that it was his command that he should not only shew me the church and all its parts, but should also narrate to me in full the histories of the several altars and chapels; and, moreover, that he should also open to me all the sacristies, and shew me their remarkable contents. I was a person to whom he was to show all honour, and who must have every cause on his return home to speak well and honourably of Messina. "Fail not," he then said, turning to me with as much of a smile as his features were capable of, – "Fail not as long as you are here to be at my dinner-table in good time – you shall always find a hearty welcome." I had scarcely time to make him a most respectful reply before the carriage moved on.

From this moment the chaplain became more cheerful, and we entered the church. The Castellan (for so we may well name him) of this fairy palace, so little suited to the worship of God, set to work to fulfil the duty so sharply enjoined on him, when Kniep and the consul rushed into the empty sanctuary, and gave vent to passionate expressions of their joy at seeing me again and at liberty, who, they had believed, would by this time have been in safe custody. They had sat in agonies until the roguish footman (whom probably the consul had well-feed) came and related with a hundred grimaces the issue of the affair; upon which a cheerful joy took possession of them, and they at once set out to seek me, as their informant had made known to them the governor's kind intentions with regard to the church, and thereby gave them a hope of finding me.

We now stood before the high altar, listening to the enumeration of the ancient rarities with which it was inlaid: pillars of lapis lazuli fluted, as it were, with bronzed and with gilded rods; pilasters and panellings after the Florentine fashion; gorgeous Sicilian agates in abundance, with bronze and gilding perpetually recurring and combining the whole together.

And now commenced a wondrous counterpointed fugue, Kniep and the consul dilating on the perplexities of the late incident, and the showman enumerating the costly articles of the well-preserved splendour, broke in alternately, both fully possessed with their subject. This afforded a twofold gratification; I became sensible how lucky was my escape, and at the same time had the pleasure of seeing the productions of the Sicilian mountains, on which, in their native state, I had already bestowed attention, here worked up and employed for architectural purposes.

My accurate acquaintance with the several elements of which this splendour was composed, helped me to discover that what was called lapis lazuli in these columns was probably nothing but calcara, though calcara of a more beautiful colour than I ever remember to have seen, and withal most incomparably pieced together. But even such as they are, these pillars are still most highly to be prized; for it is evident that an immense quantity of this material must have been collected before so many pieces of such beautiful and similar tints could be selected; and in the next place, considerable pains and labour must have been expended in cutting, splitting, and polishing the stone. But what task was ever too great for the industry of these fathers?

During my inspection of these rarities, the consul never ceased enlightening me on the danger with which I had been menaced. The governor, he said, not at all pleased that, on my very first introduction to him, I should have been a spectator of his violence towards the quasi Maltese, had resolved within himself to pay me especial attention, and with this view he had settled in his own mind a regular plan, which, however, had received a considerable check from my absence at the very moment in which it was first to be carried into effect. After waiting a long while, the despot at last sat down to dinner, without, however, been able to conceal his vexation and annoyance, so that the company were in dread lest they should witness a scene either on my arrival or on our rising from table.

Every now and then the sacristan managed to put in a word, opened the secret chambers, which are built in beautiful proportion, and elegantly not to say splendidly ornamented. In them were to be seen all the moveable furniture and costly utensils of the church still remaining, and these corresponded in shape and decoration with all the rest. Of the precious metals I observed nothing, and just as little of genuine works of art, whether ancient or modern.

Our mixed Italian-German fugue (for the good father and the sacristan chaunted in the former tongue, while Kniep and the consul responded in the latter) came to an end just as we were joined by an officer whom I remembered to have seen at the dinner-table. He belonged to the governor's suite. His appearance certainly calculated to excite anxiety, and not the less so as he offered to conduct me to the harbour, where he would take me to certain parts which generally were inaccessible to strangers. My friends looked at one another; however, I did not suffer myself to be deterred by their suspicions from going alone with him. After some talk about indifferent matters, I began to address him more familiarly, and confessed that during the dinner I had observed many of the silent party making friendly signs to me, and giving me to understand that I was not among mere strangers and men of the world, but among friends, and, indeed, brothers: and that I had, therefore, nothing to fear. I felt it a duty to thank him, and to request him to be the bearer of similar expressions of gratitude to the rest of the company. To all this he replied, that they had sought to calm any apprehensions I might have felt; because, well acquainted as they were with the character of their host, they were convinced that there was really no cause for alarm; for explosions like that with the Maltese were but very rare, and when they did happen, the worthy old man always blamed himself afterwards, and would for a long time keep a watch over his temper, and go on for a while in the calm and assured performance of his duty, until at last some unexpected rencontre would surprise and carry him away by a fresh outbreak of passion.

My valiant friend further added, that nothing was more desired by him and his companions than to bind themselves to me by a still closer tie, and therefore he begged that I would have the great kindness of letting them know where it might be done this evening, most conveniently to myself. I courteously declined the proffered honour, and begged him to humour a whim of mine, which made me wish to be looked upon during my travels merely as a man; if as such I could excite the confidence and sympathy of others, it would be most agreeable to me, and what I most wished, – but that many reasons forbade me to enter into other relations or connexions.

Convince him I could not, – for I did not venture to tell him what was really my motive. However, it struck me as remarkable, that under so despotic a government, these kind-hearted persons should have formed so excellent and so innocent an union for mutual protection, and for the benefit of strangers. I did not conceal from him the fact, that I was well aware of the ties subsisting between them and other German travellers, and expatiated at length on the praiseworthy objects they had in view; and so only caused him to feel still more surprise at my obstinacy. He tried every possible inducement to draw me out of my incognito – however, he did not succeed, partly because, having just escaped one danger, I was not inclined for any object whatever, to run into another; and partly because I was well aware that the views of these worthy islanders were so very different from my own, that any closer intimacy with them could lead neither to pleasure nor comfort.

On the other hand, I willingly spent a few hours with our well-wishing and active consul, who now enlightened us as to the scene with the Maltese. The latter was not really a mere adventurer, – still he was a restless person, who was never happy in one place. The governor, who was of a great family, and highly honored for his sincerity and habits of business, and was also greatly esteemed for his former important services, was, nevertheless, notorious for his illimitable self-will, his unbridled passion, and unbending obstinacy. Suspicious, both as an old man and a tyrant, – more anxious lest he should have, than convinced that he really had, enemies at court, he looked upon as spies, and hated all persons who, like this Maltese, were continually coming and going, without any ostensible business. This time the red cloak had crossed him, when, after a considerable period of quiet, it was necessary for him to give vent to his passion, in order to relieve his mind.

Written partly at Messina, and partly

at Sea, Monday, May 4, 1787.

Both Kniep and myself awoke with the same feelings; both felt annoyed that we had allowed ourselves, under the first impression of disgust which the desolate appearance of Messina had excited, to form the hasty determination of leaving it with the French merchantman. The happy issue of my adventure with the governor, the acquaintance which I had formed with certain worthy individuals, and which it only remained for me to render more intimate, and a visit which I had paid to my banker, whose country-house was situated in a most delightful spot: all this afforded a prospect of our being able to spend most agreeably a still longer time in Messina. Kniep, quite taken up with two pretty little children, wished for nothing more than that the adverse wind, which in any other case would be disagreeable enough, might still last for some time. In the meanwhile, however, our position was disagreeable enough, – all must be packed up, and we ourselves be ready to start at a moment's warning.

Messina – Character of the Governor

And so, at last, about mid-day the summons came; and we hastened on board, and found among the crowd collected on the shore our worthy consul, from whom we took our leave with many thanks. The sallow footman, also, pressed forward to receive his douceur – he was accordingly duly rewarded, and charged to mention to his master the fact of our departure, and to excuse our absence from dinner. "He who sails away is at once excused," exclaimed he; and then turning round with a very singular spring, quickly disappeared.