Letters from Switzerland and Travels in Italy

When they heard that I was soon to depart from Palermo, they became still more urgent, and entreated me to come back again at all events; especially they praised the heavenly day of S. Rosalie's festival, the like of which was not to be seen or enjoyed in the world.

My guide, who for a long while had been wishing to get away, at last by his signs put an end to our talk, and I promised to come on the evening of the next day, and fetch the letter. My guide expressed his satisfaction that all had gone off so well, and we parted, well satisfied with each other.

You may imagine what impression this poor, pious, and well-disposed family made upon me. My curiosity was satisfied; but their natural and pleasing behaviour had excited my sympathy, and reflection only confirmed my good will in their favour.

Palermo – Count Cagliostro

But then some anxiety soon arose in my mind about to-morrow. It was only natural that my visit, which at first had so charmed them, would, after my departure, be talked and thought over by them. From the pedigree I was aware that others of the family were still living. Nothing could be more natural than that they should call in their friends to consult them on all that they had been so astonished to hear from me the day before. I had gained my object, and now it only remained for me to contrive to bring this adventure to a favourable issue. I therefore, set off the next day, and arrived at their house just after their dinner. They were surprised to see me so early. The letter, they told me, was not yet ready; and some of their relatives wished to make my acquaintance, and they would be there towards evening.

I replied that I was to depart early in the morning; that I had yet some visits to make, and had also to pack up, and that I had determined to come earlier than I had promised rather than not come at all.

During this conversation the son entered, whom I had not seen the day before. In form and countenance he resembled his sister. He had brought with him the letter which I was to take. As usual in these parts, it had been written by one of the public notaries. The youth who was of a quiet, sad, and modest disposition, inquired about his uncle, asked about his riches and expenditure, and added, "How could he forget his family so long? It would be the greatest happiness to us," he continued, "if he would only come back and help us but he further asked, "How came he to tell you that he had relations in Palermo? It is said that he everywhere disowns us, and gives himself out to be of high birth." These questions, which my guide's want of foresight on our first visit had given rise to, I contrived to satisfy, by making it appear possible that, although his uncle might have many reasons for concealing his origin from the public, he would, nevertheless make no secret of it to his friends and familiar acquaintances.

His sister, who had stepped forward during this conversation, and who had taken courage from the presence of her brother, and probably, also, from the absence of yesterday's friend, began now to speak. Her manner was very pretty and lively. She earnestly begged me, when I wrote to her uncle, to commend her to him; and not less earnestly, also, to come back when I had finished my tour through the kingdom of Sicily, and to attend with them the festivities of S. Rosalie.

The mother joined her voice to that of her children. "Signor," she exclaimed, "although it does not in propriety become me, who have a grown-up daughter, to invite strange men to my house, – and one ought to guard not only against the danger itself, but even against evil tongues, – still you, I can assure you, will be heartily welcome, whenever you return to our city."

"Yes! yes!" cried the children, "we will guide the Signor throughout the festival; we will show him every thing; we will place him on the scaffolding from which you have the best view of the festivities. How delighted will he be with the great car, and especially with the splendid illuminations!"

In the mean while, the grandmother had read the letter over and over again. When she was told that I wished to take my leave, she stood up and delivered to me the folded paper. "Say to my son," she said, with a noble vivacity, not to say enthusiasm, "tell my son how happy the news you have brought me of him has made us. Say to my son, that I thus fold him to my heart," (here she stretched out her arms and again closed them over her bosom) – "that every day in prayer I supplicate God and our blessed Lady for him; that I give my blessing to him and to his wife, and that I have no wish but, before I die, to see him once again, with these eyes, which have shed so many tears on his account."

The peculiar elegance of the Italian favoured the choice and the noble arrangement of her words, which, moreover, were accompanied with those very lively gestures, by which this people usually give an incredible charm to everything they say. Not unmoved, I took my leave; they all held out their hands to me: the children even accompanied me to the door, and while I descended the steps, ran to the balcony of the window which opened from the kitchen into the street, called after me, nodded their adieus, and repeatedly cried out to me not to forget to come again and see them. They were still standing on the balcony, when I turned the corner.

I need not say that the interest I took in this family excited in me the liveliest desire to be useful to them, and to help them in their great need. Through me they were now a second time deceived, and hopes of assistance, which they had no previous expectation of, had been again raised, through the curiosity of a son of the north, only to be disappointed.

Palermo – Count Cagliostro

My first intention was to pay them before my departure these fourteen once, which, at his departure, the fugitive was indebted to them, and by expressing a hope that he would repay me, to conceal from them the fact of its being a gift from myself. When, however, I got home, and cast up my accounts, and looked over my cash and bills, I found that, in a country where, from the want of communication, distance is infinitely magnified, I should perhaps place myself in a strait if I attempted to make amends for the dishonesty of a rogue, by an act of mere good nature.

The subsequent issue of this affair may as well be here introduced.

I set off from Palermo, and never came back to it; but notwithstanding the great distance of my Sicilian and Italian travels, my soul never lost the impression which the interview with this family had left upon it.

I returned to my native land, and the letter of the old widow, turning up among the many other papers, which had come with it from Naples by sea, gave me occasion to speak of this and other adventures.

Below is a translation of this letter, in which I have purposely allowed the peculiarities of the original to appear.

"My Dearest Son,

"On the 16th April, 1787, I received tidings of you through Mr. Wilton, and I cannot express to you how consoling it was to me; for ever since you removed from France, I have been unable to hear any tidings of you.

"My dear Son, – I entreat you not to forget me, for I am very poor, and deserted by all my relations but my daughter, and your sister Maria Giovanna, in whose house I am living. She cannot afford to supply all my wants, but she does what she can. She is a widow, with three children: one daughter is in the nunnery of S. Catherine, the other two children are at home with her.

"I repeat, my dear son, my entreaty. Send me just enough to provide for my necessities; for I have not even the necessary articles of clothing to discharge the duties of a Catholic, for my mantle and outer garments are perfectly in rags.

"If you send me anything, or even write me merely a letter, do not send it by post, but by sea; for Don Mattéo, my brother (Bracconeri), is the postmaster.

"My dear Son, I entreat you to provide me with a tari a-day, in order that your sister may, in some measure, be relieved of the burthen I am at present to her, and that I may not perish from want. Remember the divine command, and help a poor mother, who is reduced to the utmost extremity. I give you my blessing, and press to my heart both thee and Donna Lorenza, thy wife.

"Your sister embraces you from her heart, and her children kiss your hands.

"Your mother, who dearly loves you, and presses you to her heart.

"Felice Balsamo."Palermo, April 18, 1787."

Some worthy and exalted persons, before whom I laid this document, together with the whole story, shared my emotions, and enabled me to discharge my debt to this unhappy family, and to remit them a sum which they received towards the end of the year 1787. Of the effect it had, the following letter is evidence.

"Palermo, December 25, 1787.

"Dear and Faithful Brother,

"Dearest Son,

"The joy which we have had in hearing that you are in good health and circumstances, we cannot express by any writing. By sending them this little assistance, you have filled with the greatest joy and delight a mother and a sister who are abandoned by all, and have to provide for two daughters and a son: for, after that Mr. Jacob Joff, an English merchant had taken great pains to find out the Donna Giuseppe Maria Capitummino (by birth Balsamo), in consequence of my being commonly known, merely as Marana Capitummino, he found us at last in a little tenement, where we live on a corresponding scale. He informed us that you had ordered a sum of money to be paid us, and that he had a receipt, which I, your sister, must sign – which was accordingly done; for he immediately put the money in our hands, and the favorable rate of the exchange has brought us a little further gain.

"Now, think with what delight we must have received this sum, at a time when Christmas Day was just at hand, and we had no hope of being helped to spend it with its usual festivity.

"The Incarnate Saviour has moved your heart to send us this money, which has served not only to appease our hunger, but actually to clothe us, when we were in want of everything.

"It would give us the greatest gratification possible if you would gratify our wish to see you once more – especially mine, your mother, who never cease to bewail my separation from an only son, whom I would much wish to see again before I die.

"But if, owing to circumstances, this cannot be, still do not neglect to come to the aid of my misery, especially as you have discovered so excellent a channel of communication, and so honest and exact a merchant, who, when we knew nothing about it, and when he had the money entirely in his own power, has honestly sought us out and faithfully paid over to us the sum you remitted.

"With you that perhaps will not signify much. To us, however, every help is a treasure. Your sister has two grown up daughters, and her son also requires a little help. You know that she has nothing in the world; and what a good act will you not perform by sending her enough to furnish them all with a suitable outfit.

"May God preserve you in health! We invoke Him in gratitude, and pray that He may still continue the prosperity you have hitherto enjoyed, and that He may move your heart to keep us in remembrance. In His name I bless you and your wife, as a most affectionate mother – and I your sister, embrace you: and so does your nephew, Giuseppe (Bracconeri), who wrote this letter. We all pray for your prosperity, as do also my two sisters, Antonia and Theresa.

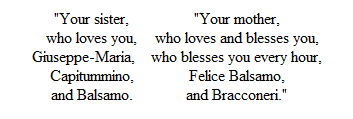

"We embrace you, and are,

The signatures to the letter are in their own handwriting. I had caused the money to be paid to them without sending any letter, or intimation whence it came; this makes their mistake the more natural, and their future hopes the more probable.

Now, that they have been informed of the arrest and imprisonment of their relative, I feel myself at liberty to explain matters to them, and to do something for their consolation. I have still a small sum for them in my hands, which I shall remit to them, and profit by the opportunity to explain the true state of the matter. Should any of my friends, should any of my rich and noble countrymen, be disposed to enlarge, by their contributions, the sum I have already in my hands, I would exhort them in that case to forward their land gifts to me before Michaelmas-day, in order to share the gratitude, and to be rewarded with the happiness of a deserving family, out of which has proceeded one of the most singular monsters that has appeared in this century.

I shall not fail to make known the further course of this story, and to give an account of the state in which my next remittance finds the family; and perhaps also I shall add some remarks which this matter induced me to make, but which, however, I withhold at present in order not to disturb my reader's first impressions.

Palermo, April 14, 1787.

Towards evening I paid a visit to my friend the shop-keeper, to ask him how he thought the festival was likely to pass off; for to-morrow there is to be a solemn procession through the city, and the Viceroy is to accompany the host on foot. The least wind will envelop both man and the sacred symbols in a thick cloud of dust.

With much humour he replied: In Palermo, the people look for nothing more confidently than for a miracle. Often before now on such occasions, a violent passing shower had fallen and cleansed the streets partially at least, so as to make a clean road for the procession. On this occasion a similar hope was entertained, and not without cause, for the sky was overcast, and promised rain during the night.

Palermo, Sunday, April 15, 1787.

And so it has actually turned out! During the night the most violent of showers have fallen. In the morning I set cut very early in order to be an eye-witness of the marvel. The stream of rain-water pent up between the two raised pavements had carried the lightest of the rubbish down the inclined street, either into the sea or into such of the sewers as were not stopped up, while the grosser and heavier dung was driven from spot to spot. In this a singular meandering line of cleanliness was marked out along the streets. On the morning hundreds and hundreds of men were to be seen with brooms and shovels, busily enlarging this clear space, and in order to connect it where it was interrupted by the mire; and throwing the still remaining impurities now to this side, now to that. By this means when the procession started, it found a clear serpentine walk prepared for it through the mud, and so both the long robed priests and the neat-booted nobles, with the Viceroy at their head, were able to proceed on their way unhindered and unsplashed.

I thought of the children of Israel passing through the waters by the dry path prepared for them by the hand of the Angel, and this remembrance served to ennoble what otherwise would have been a revolting sight – to see these devout and noble peers parading their devotions along an alley, flanked on each side by heaps of mud.

Palermo – Its streets

On the pavement there was now, as always, clean walking; but in the more retired parts of the city whither we were this day carried in pursuance of our intention of visiting the quarters which we had hitherto neglected, it was almost impossible to get along, although even here the sweeping and piling of the filth was by no means neglected.

The festival gave occasion to our visiting the principal church of the city and observing its curiosities. Being once on the move, we took a round of all the other public edifices. We were much pleased with a Moorish building, which is in excellent preservation – not very large, but the rooms beautiful, broad, and well proportioned, and in excellent keeping with the whole pile. It is not perhaps suited for a northern climate, but in a southern land a most agreeable residence. Architects may perhaps some day furnish us with a plan and elevation of it.

We also saw in most unsuitable situations various remains of ancient marble statues, which, however, we had not patience to try to make out.

Palermo, April 16, 1787.

As we are obliged to anticipate our speedy departure from this paradise, I hoped to-day to spend a thorough holiday by sitting in the public gardens; and after studying the task I had set myself out of the Odyssey, taking a walk through the valley, and at the foot of the hill of S. Rosalie, thinking over again my sketch of Nausicaa, and there trying whether this subject is susceptible of a dramatic form. All this I have managed, if not with perfect success, yet certainly much to my satisfaction. I made out the plan, and could not abstain from sketching some portions of it which appeared to me most interesting, and tried to work them out.

Palermo, Tuesday, April 17, 1787.

It is a real misery to be pursued and hunted by many spirits! Yesterday I set out early for the public gardens, with a firm and calm resolve to realize some of my poetical dreams; but before I got within sight of them, another spectre got hold of me which has been following me these last few days. Many plants which hitherto I had been used to see only in pots and tubs, or under glass-frames, stand here fresh and joyous beneath the open heaven, and as they here completely fulfil their destination, their natures and characters became more plain and evident to me. In presence of so many new and renovated forms, my old fancy occurred again to me: Might I not discover the primordial plant among all these numerous specimens? Some such there must be! For, otherwise, how am I able at once to determine that this or that form is a plant unless they are all formed after one original type? I busied myself, therefore, with examining wherein the many varying shapes differed from each other. And in every case I found them all to be more similar than dissimilar, and attempted to apply my botanical terminology. That went on well enough; still I was not satisfied; I rather felt annoyed that it did not lead further. My pet poetical purpose was obstructed; the gardens of Antinous all vanished – a real garden of the world had taken their place. Why is it that we moderns have so little concentration of mind? Why is it that we are thus tempted to make requisitions which we can neither exact nor fulfil?

Alcamo, Wednesday, April 18, 1787.

At an early hour, we rode out of Palermo. Kniep and the Vetturino showed their skill in packing the carnage inside and out. We drove slowly along the excellent road, with which we had previously become acquainted during our visit to San Martino, and wondered a second time at the false taste displayed in the fountains on the way. At one of these our driver stopped to supply himself with water according to the temperate habits of this country. He had at starting, hung to the traces a small wine-cask, such as our market-women use, and it seemed to us to hold wine enough for several days. We were, therefore, not a little surprised when he made for one of the many conduit pipes, took out the plug of his cask, and let the water run into it. With true German amazement, we asked him what ever he was about? was not the cask full of wine? To all which, he replied with great nonchalance: he had left a third of it empty, and as no one in this country drank unmixed wine, it was better to mix it at once in a large quantity, as then the liquids combined better together, and besides you were not sure of finding water everywhere. During this conversation the cask was filled, and we had some talk together of this ancient and oriental wedding custom.

And now as we reached the heights beyond Mon Reale, we saw wonderfully beautiful districts, but tilled in traditional rather than in a true economical style. On the right, the eye reached the sea, where, between singular shaped head-lands, and beyond a shore here covered with, and there destitute of, trees, it caught a smooth and level horizon, perfectly calm, and forming a glorious contrast with the wild and rugged limestone rocks. Kniep did not fail to take miniature outlines of several of them.

Alcamo

We are at present in Alcamo, a quiet and clean little town, whose well-conducted inn is highly to be commended as an excellent establishment, especially as it is most conveniently situated for visitors to the temple of Segeste, which lies out of the direct road in a very lonely situation.

Alcamo, Thursday, April 19, 1787.

Our agreeable dwelling in this quiet town, among the mountains, has so charmed us that we have determined to pass a whole day here. We may then, before anything else, speak of our adventures yesterday. In one of my earlier letters, I questioned the originality of Prince Pallagonia's bad taste. He has had forerunners and can adduce many a precedent. On the road towards Mon Reale stand two monstrosities, beside a fountain with some vases on a balustrade, so utterly repugnant to good taste that one would suppose they must have been placed there by the Prince himself.

After passing Mon Reale, we left behind us the beautiful road, and got into the rugged mountain country. Here some rocks appeared on the crown of the road, which, judging from their gravity and metallic incrustations, I took to be ironstone. Every level spot is cultivated, and is more or less prolific. The limestone in these parts had a reddish hue, and all the pulverized earth is of the same colour. This red argillaceous and calcareous earth extends over a great space; the subsoil is hard; no sand underneath; but it produces excellent wheat. We noticed old very strong, but stumpy, olive trees.

Under the shelter of an airy room, which has been built as an addition to the wretched inn, we refreshed ourselves with a temperate luncheon. Dogs eagerly gobbled up the skins of the sausages we threw away, but a beggar-boy drove them off. He was feasting with a wonderful appetite on the parings of the apples we were devouring, when he in his turn was driven away by an old beggar. Want of work is here felt everywhere. In a ragged toga the old beggar was glad to get a job as house-servant, or waiter. Thus I had formerly observed that whenever a landlord was asked for anything which he had not at the moment in the house, he would send a beggar to the shop for it.

However, we are pretty well provided against all such sorry attendance; for our Vetturino is an excellent fellow – he is ready as ostler, cicerone, guard, courier, cook, and everything.

On the higher hills you find every where the olive, the caruba, and the ash. Their system of farming is also spread over three years. Beans, corn, fallow; in which mode of culture the people say the dung does more marvels than all the Saints. The grape stock is kept down very low.

Alcamo is gloriously situated on a height, at a tolerable distance from a bay of the sea. The magnificence of the country quite enchanted us. Lofty rocks, with deep valleys at their feet, but withal wide open spaces, and great variety. Beyond Mon Beale you look upon a beautiful double valley, in the centre of which a hilly ridge again raises itself. The fruitful fields lie green and quiet, but on the broad roadway the wild bushes and shrubs are brilliant with flowers – the broom one mass of yellow, covered with its pupilionaceous blossoms, and not a single green leaf to be seen; the white-thorn cluster on cluster; the aloes are rising high and promising to flower; a rich tapestry of an amaranthine-red clover, of orchids and the little Alpine roses, hyacinths, with unopened bells, asphodels, and other wild flowers.

Sicily – Segeste

The streams which descend from M. Segeste leave deposits, not only of limestone, but also of pebbles of horn-stone. They are very compact, dark blue, yellow, red, and brown, of various shades. I also found complete lodes of horn, or fire-stone, in the limestone rocks, edged with lime. Of such gravel one finds whole hills just before one gets to Alcamo.

Segeste, April 20, 1787.

The temple of Segeste was never finished; the ground around it was never even levelled; the space only being smoothed on which the peristyle was to stand. For, in several places, the steps are from nine to ten feet in the ground, and there is no hill near, from which the stone or mould could have fallen. Besides, the stones lie in their natural position, and no ruins are found near them.