По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

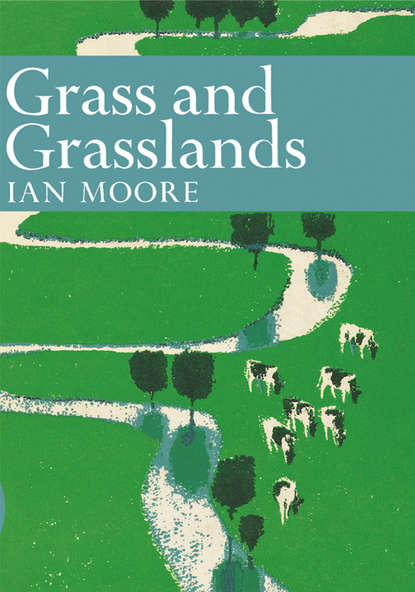

Grass and Grassland

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Our life is so inextricably interwoven with that of the grasses which grace our fields that the study of grassland is both fascinating and intriguing to all who possess an inquiring mind, be they born and bred in towns or sons of the soil. What is more, the management of the grass sward for farming, sport or pleasure offers a real challenge to skill, in the feeding of plants and the tending of them throughout their life, as well as to one’s understanding of technical developments in the realm of botany, chemistry, engineering and economics.

Where should we be without grass? Our life is so dependent on this humble, oft-neglected plant that we must appreciate its real significance in the nation’s economy. Without grass our country would lose its scenic beauty, so many sports their colourful background and in scores of ways our lives would be changed. The ordinary grass field one sees every day on any farm, the sports ground with which one is so familiar at school or college or in the wider arena of national games, the small patch of green which graces the front or back of so many English homes, is a complex community of plants each displaying likes and dislikes, and different reactions to varying treatment, yet supplying an essential need whether on the world or simply the individual scale.

For over thirty years my special interest has been grassland and when I was asked by the Editors of the New Naturalist Series to present the story of grassland for their readers, I accepted with alacrity.

In writing such a book one must draw from many sources of knowledge and from many writers of the past and I hope I have made due acknowledgements to the many who have contributed to our understanding of grassland. I am deeply indebted to my own colleagues in College for their ready help and guidance and particularly to Mr. K. C. Vear, Professor H. T. Williams and Mr. R.J. Halley. Not being a botanist, I have had much assistance from Mr. Vear, Head of the Biology Department and as I am not an economist, Professor Williams, formerly Head of Agricultural Economics and now of the University of Aberystwyth, has been of material assistance with Chapter 16; Mr. Halley has given me invaluable assistance with the more practical aspects of grassland husbandry, and Mr. R. W. Younger with Chapter 18. To Mr. D. J. Barnard I am very indebted for help with the proofs.

To the Editors I am grateful for their help in the preliminary stages of writing the book, while to Mr. John Gilmour I am especially indebted for his most valuable criticism and guidance at all stages of preparation. While I hope the book will have a wide appeal generally, I am particularly hopeful that the many schools throughout the country now using a school plot or a school farm or maybe a neighbour’s farm as a living medium for teaching, will find it of value. To the many students now attending the recently instituted day-release classes organised by County Education Authorities in agriculture, to those at Farm Institutes and to all students gaining practical experience prior to College or University courses I hope this book will serve as encouragement to a deeper appreciation of the value of the grass crop and an added incentive to further investigation and wider reading.

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_0b3690a6-7d8a-5b71-8053-515c1981d2a9) THE ROLE OF GRASS IN NATIONAL LIFE

The significance of grass in the life of man was recognised in earliest times but the distractions of modern life in great cities and the speed with which man now passes through the countryside have caused him to underestimate its importance.

Wherever one travels throughout the British Isles grass is to be seen. Our temperate climate and high rainfall, especially in the western areas, favour the growth of grass which in some parts has a growing season of nine months a year, from March to November. Grassland farming, therefore, is our predominant type of farming, and the efficient production and utilisation of grass are obviously of the greatest economic significance to British agriculture. Agriculture is still Britain’s largest single industry and the annual turnover accounts for about 5 per cent of the gross national product thereby exceeding coal (3.2 per cent) and iron and steel (2.8 per cent) which are the next largest industries in gross output. In turn grass, which is our most important crop, makes the greatest single contribution to the farming income. This apart, grass is of prime importance for leisure hours, and our playing fields, which are so much a part of our national life, depend upon grass.

There is obviously a wide range in the types of grassland found in this country, according to the purpose for which they are used. These include bowling greens and cricket pitches with their velvet, close-knit turf, pastures which fatten cattle or carry large herds of milch cows, and moorland sheep walks. Nor must one forget the importance even of the small garden lawn. This may well be the pride of the owner, who mows it with great care each week-end in the summer months. Each type of turf requires specialised treatment and the potential productivity of the different types of farm grassland—permanent meadows, pastures and cultivable leys as well as the rolling hills and moorland which are classified as rough grazings—varies greatly.

Grass provides some two-thirds of the total requirements in terms of starch, and even more in terms of protein, of all the cattle, sheep, and horses in the country. This is shown vividly by the following figures for the area under crops and grass in the United Kingdom in 1961.

TABLE I. AREA UNDER CROPS AND GRASS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

The astonishing fact is revealed that on 4th June, 1961, when these agricultural returns were made, some nine-tenths of our farmland was under grass of one sort or another, i.e. members of the family Gramineae.

Grass is not, in the great majority of cases, a natural clothing for the earth’s surface, provided by a beneficent nature. It is a community of widely differing species and varieties of plants living together in a constant struggle one with another and overshadowed always by the threat of being overwhelmed by weeds, rushes, bracken, heather, gorse, thorns, alder and other trees until, if man allows this process to go unchecked, scrub or even forest reigns supreme once more. Even the patch of lawn is subjected to the same forces and only by constant attention is a weed-free, close-knit, verdant green turf maintained.

During the lean times of farming in the 1920’s and 30’s, thousands of acres of farm land reverted to derelict grass and scrub, the farmers being forced to save labour, cut out expensive arable crops, and be satisfied with mere subsistence standards of life, since following the first world war the prices obtained for many farm products were less than the cost of production. Then too, in those days cheap imported cattle cakes and food were readily available, which could serve as a substitute for the grass normally fed to stock, not only during the winter months but even in summer. It was by no means uncommon for dairy herds in industrial areas, such as those in Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire, for instance, to be fed wholly on imported feeding stuffs. In extreme cases the cows probably never left the byre, except perhaps to take exercise in a nearby field during the summer months. Under these conditions the productivity of the grassland was negligible and mineral deficiencies in the soil determined that the land was little more than exercise ground.

Grass is a crop requiring the same care and attention as wheat, potatoes, or sugar beet. It needs cultivating, fertilising, and utilising to best advantage and when it receives this treatment the returns per acre can be as high as from any other crop. Moreover, it has a valuable function in restoring fertility to the soil. In two world wars, by ploughing up a large proportion of our grassland and cropping with cereals, good crops were produced with the minimum of fertiliser, valuable shipping space was saved and a decisive contribution to victory was made.

Mention has been made of the fertility-restoring power of grass and one may rightly ask how this is brought about. The very serious problems of erosion which concern authorities in various parts of the world serve to highlight this vital question of soil conservation. Soil fertility is dependent upon good tilth, maximal water and air, and maximal plant nutrients. Tilth represents the physical condition of the soil in relation to plant growth and each crop has its own requirements for a seed bed. Ploughing, rotovating, cultivating, disc harrowing, and the use of rollers and spiked harrows disturb the soil so that it becomes granular in structure and suitable for the reception of small seeds, yet capable of resisting the shattering and erosive effects of heavy rain until such time as the crop itself provides a close canopy which protects the soil and prevents the fine particles from being washed away by flood waters.

The soil needs to have what is termed “structure.” The extremes are sand, which is devoid of structure, on the one hand, and clay, in which the particles are so small that pore space for air and water is virtually non-existent, on the other. Between these extremes lies a “crumb structure” with aggregated particles usually greater than 0.5 mm. in diameter and preferably from 1 to 55 mm. in diameter. When this crumb structure is attained the soil has the capacity to hold enough moisture for the needs of the crop and can resist both “drying-out” during periods of drought and the mechanical stresses of farm equip ment. Flora and fauna play their part in achieving this ideal through the medium of microbiological activity in the decomposition of organic matter and in fixing atmospheric nitrogen through the medium of leguminous plants. Grassland swards have a vital role to play in the maintenance of fertility since they contain legumes in most cases and when ploughed provide necessary organic matter.

Sandy soils have the advantage of free drainage, good aeration and ease of cultivation, as any gardener on a sandy soil will admit. But these are often too loose and too open in texture and lack the capacity to absorb and hold water and plant nutrients. They are termed “hungry” soils and the limitations of such soils are best overcome by grasses, the fine roots of which physically bind together the mineral particles. Farmyard manure, and green crops which are ploughed in—“green manuring”—perform the same function but a good deal less effectively and at considerably higher cost to the farmer or gardener. Moreover, a long ley or permanent grass sward gives complete coverage from storm water and thus prevents erosion.

Clay soils are very finely-textured and retain moisture to such an extent that a field may be unworkable for several months in the year. Clay is a colloid and therefore very cohesive and highly plastic. Thus when clay soils are cultivated in too wet a condition they become even stickier and are said in farming terms to “poach.” Poached land dries out into hard, intractable clods which defy all the efforts of man and machine to break them down to produce a seed bed. In this case granulation of the clay particles to form aggregates—“flocculation” to the chemist—must be brought about, and here again grasses and deep-rooting clovers have a vital role to perform. Farmyard manure, though more effective with clay than with sandy soils, does not increase soil permeability to the same extent as do the fibrous roots of grasses.

I hope I have stressed adequately this unseen function of our grassland. Most people understand the milk or meat-producing relationship between our grassland and the needs of man. Very few appreciate how essential the grass plant is to the whole cropping system of the country.

Grass provides the cheapest way of feeding herbivorous animals during its growing season, while grass conserved as silage or hay, or dried by artificial means, can be used for feeding during the winter months. The following table compares the cost of each food unit (“starch equivalent”) from various forms of grass with other succulent foods and clearly underlines the vital necessity of having an adequate supply of fresh grass for feeding.

TABLE 2. COST OF STARCH EQUIVALENTS

Recent research work both in the United States and on farms in this country points to the fact that it may be cheaper and more efficient to mow the grass during the summer months and cart it to the cows, which remain in covered yards—a practice known as “zero grazing,” “green soiling” or “mechanical grazing”—rather than to allow the cattle to graze. We shall deal with this question later on.

What are the products of grass? It contributes some 67 per cent of the total feed requirements of all our livestock and since pigs only account for about 3 per cent and poultry 6 per cent, it means that grass provides on the average at least 70 per cent of the diet of cattle and sheep and the few goats. Home-produced veal, beef, mutton, and lamb, our leather and wool, our milk, butter, and cheese, are largely the final product of grass. Few realise the magnitude of these products and their importance to the economy of the country. The table below gives some idea:

TABLE 3. THE GROSS OUTPUT FROM ANIMALS MAINLY DEPENDENT UPON GRASS—UNITED KINGDOM 1961–2

If grass contributes 70 per cent of the total feed requirements of the above stock groups, £492,300,000 of production can be attributed to grassland. This figure represents 31 per cent of the £1,592,000,000 output from national agriculture in 1961–2.

We are all eaters and users of grass. Numbered within the great grass family Gramineae are the cereals—wheat, barley, oats, rye, maize, rice, millet, and sorghum—which provide many of our staple foods. Most of the world’s really fertile grassland areas grow cereals so well when ploughed that they are known as “bread baskets.” In this category fall the wide prairies of the United States and Canada, the vast grain belts of the Ukraine and Australia, and the pampas of Argentina. Cane sugar is derived from a grass (Saccharum officinale). Those giants amongst the grasses, the bamboos, include majestic trees towering to a height of a hundred and twenty feet and some three feet in circumference, forming impenetrable forests as well as providing a variety of useful articles from musical pipes to furniture and domestic utensils. Some grasses are necessary to bind sand and combat the encroaching sea which at certain points along our coastline is ever striving to engulf more and more land. Other grasses provide fragrant oils and perfumes. Lemon grass or Indian grass (Cymbopogon citratus), which grows wild in India, is also cultivated both there and in Ceylon and is used for infusing a tea which is reputed to have medicinal properties. Andropogon nardus is cultivated in Ceylon and Singapore for the production of citronella oil which is used extensively in the manufacture of soaps and perfumes as well as for the treatment of rheumatism in India. Finally, still other grasses provide the turf we use for sport and recreation.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_9923fa75-7046-5e17-a8a7-71b1ce4a0a64) THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF GRASSLAND

For many generations the term “grasses” as used by farmers had an all-embracing significance and included companion plants like clovers, yarrow, dandelion, ribgrass, and so on, the blending of which made up the turf or sward of a pasture or a meadow which was eaten by horses, sheep and cattle. The term “pasture” usually refers to grassland grazed by animals, while “meadows” are mown for hay. These terms are often used loosely and frequently synonymously, for grassland may be grazed and mown in the same year. Moreover, grazing land is commonly referred to as “meadow” when it borders a stream or river, and in all probability in days gone by it was our poets who contributed to this confusion of terminology. Only in recent years have farmers consciously distinguished between the various plant species composing a particular type of grassland and realised the significance of the grazing animal or the mowing machine in determining the botanical composition of a particular sward or piece of turf. The groundsman, unlike the farmer, abhors all plants other than the special grasses required to produce a hard-wearing turf. Thus the clovers and other miscellaneous plants commonly seen in farm swards and indeed encouraged to flourish there, are eliminated as speedily as possible by both mechanical and chemical agencies when found in the domestic lawn, the cricket field or the golf green.

The history of our grasses from the Ice Age can be traced through the pollen grains which have remained preserved for thousands of years in peat bogs. The pollen of many plants, including the bulk of our forest trees, is liberated in vast showers of golden dust, and is wind-borne for considerable distances. Even the centres of large cities receive their quota as the sufferers from hay fever know to their cost. Each pollen grain is protected by a thin skin which is highly resistant to decay; consequently when down the ages millions upon millions of these grains have settled on the land and been covered by further deposits they have not disintegrated. It is possible in the laboratory to separate the pollen grains from soil particles obtained by the simple process of boring into ancient lake beds and peat bogs. These can be identified and in this way precise records of the local vegetation can be secured from the glacial period onwards. Such information can then be cross-checked with any geological and archaeological data available enabling a complete picture to be built up.

With the improvement in climate after the final retreat of the ice, the country was covered with vast woods of pine and birch, the only grassland being in parts of the forest cleared by early man. Then elm, oak, and hazel scrub gradually became established as conditions improved.

What of the livestock whose development is intimately interwoven with that of the grasses? Animals clearly related to our present-day grazing animals appear in the fossil records early in the Eocene period, some seventy million years ago. Judging by the structure and arrangement of their teeth, these early ungulates were, however, mainly browsing animals, feeding by cropping the leaves of forest trees. This seems to have been true throughout the Eocene and the succeeding Oligocene period, but at the opening of the Miocene, some forty million years later, there appears to have been a decrease in rainfall and a consequent diminution of forest cover, leaving grasses and other low-growing plants in possession of the plains, both in the Old and the New World. True grazing animals, closely related to modern types, then developed. Antelopes and sheep are recognisable from the Upper Miocene, and oxen, goats, and horses from the following Pliocene period.

The pastures which supplied the needs of the stock of primitive man were as can be imagined but a pale shadow of the excellent swards of to-day. It is unlikely that they did more than keep mature cattle alive, although for a short period during the summer months the best milk cows might have produced a few pints of milk per day, compared to the four, five or six gallons expected now. Nor was the farmer of those times conversant with the needs of the soil, and the constant leaching of nutrients by rain water and the removal of minerals by the stock themselves in the herbage consumed meant that phosphate, lime and potash deficiencies were common. As the fertility of the cultivated ground fell to the point where the yield of grain no longer rewarded the efforts of cultivation, this ground was abandoned. The former arable was then allowed to revert to some form of grass again. Such conditions favour the growth of mat grass (Nardus stricta), purple moor grass (Molinia caerulea) sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina), bent (Agrostis spp.), bromes (Bromus spp.) and the oat grasses (Arrhena-therum, Trisetum and Helictotrichon), grasses of poor feeding value. These are in marked contrast to the broad-leaved succulent grasses of high feeding value which comprise a good pasture. Farm stock in those early times was small and stunted as shown by the skeletons which have been found and this was only to be expected under such conditions.

The conversion from forest to pasture can be seen in minature on the broad verge of many a farm road crossing or common. Nearest the road, the constant trampling back and forth of cattle, sheep, and horses promotes the growth of the best pasture grasses, such as the ryegrasses (Lolium spp.) and the meadow grasses (Poa spp.) with wild white clover (Trifolium repens) and probably bird’s foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus). As the trampling and grazing become less intensive further from the road-side so the bents (Agrostis spp.) the fescues (Festuca spp.) and Yorkshire fog (Holcus lanatus) become more dominant and these in turn are replaced by coarser grasses, the tall fescues, tussock grass (Deschampsia caespitosa) and oat grasses until bramble, hazel, blackthorn, wild rose, and hawthorn dominate the scene. It is then only a short step to true forest. This gradual progression from good grass to forest follows any change which results in less intensive grazing or neglect. Should a field be ranched, allowing only a few head of stock on a large acreage of grassland, as opposed to close grazing where many stock are concentrated in a field, or more especially if grassland is allowed to become derelict, young saplings of forest trees spring up and the once valuable turf soon becomes colonised by coarse grasses and scrubby growths reverting back in time to the original forest from which the pasture had been won by the efforts of man.

Not until about 50 B.C. was the liming and marling of fields practised by the Belgae as a means of replenishing the fertility of the soil, and it was very much later that the droppings of animals were collected to be spread as farmyard manure. We owe much to the Belgae; with the eight-ox plough which they introduced, cultivation on a much bigger scale became possible and, moreover, they affected considerable forest clearance with their implements. So successful were their efforts, indeed, that corn and cattle were exported to the Continent, and when Caesar invaded Britain he was able to supply the food needs of his troops from the soil of Kent.

The Romans did little for the grassland of Britain, but after they had withdrawn, the Anglo-Saxon invaders, with great vigour, began clearing more forest land and converting lowland soils into meadows and cornfields. Many more were enclosed for better cropping and compact villages were created. These were usually surrounded by large open fields in which each settler had a number of scattered strips, some for cultivation and others to be mown for hay, the underlying principle being to divide up as evenly as possible the different types of soil with their varying levels of fertility. After harvest the arable and the meadow land were opened for common grazing, the stock feeding on the straw which was left on the arable ground, together with any growth of grass which had been made since the hay was carted. The Anglo-Saxons were really the first farmers to appreciate the need for adequate pasture during the grazing season and the necessity of safeguarding their stock in winter time with a good supply of hay. By so doing, the former practice of slaughtering in the autumn all the stock which could not fend for itself during the winter was avoided. Each occupier of thirty acres was given at the beginning of his tenancy a cow, two oxen, and six sheep by the lord of the manor and there were no farmers who merely rented the land as they do now. It was possible to increase the acreage of pasture by paying money rent to the lord or by rendering services in the form of additional ploughing. The Anglo-Saxon period was fruitful for Britain, and central and eastern England was dotted with villages which were later recorded in Domesday Book. It was a period of winning from the forest, of settlement, and of organised farming.

Domesday Book includes a remarkably comprehensive survey of the land initiated by King William to ensure accurate assessment and punctual payment of tax. The prosperity of each manor depended upon the amount of land which could be ploughed; in essence, upon the strength of its oxen. Plough-teams were in their turn dependent upon an adequate supply of meadow hay for the winter and so large fertile meadows were the key to the farming economy of those days. This is seen in the relative value per acre of meadow land compared with arable, the former often being worth four times as much as the latter. The value of enclosed pasture was usually less than that of meadow land, while the common pasture land in many instances surrounded the village and gradually merged into scrub and woodland which served as a line of demarcation between neighbouring villages. The scarcity of good pasture is a constant theme of all manorial documents of the period.

Reclamation was continued until around A.D. 1500. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were the period of greatest colonising activity in England, but this colonisation drive was largely over by about A.D. 1300. Pressure of population seems to have kept peasant demand for land at a high level up to the Black Death in A.D. 1349 although there was considerable contraction of the arable, and hence an increase in grassland, on many estates before A.D. 1300 or very soon afterwards. The Black Death resulted in the death of large numbers of labourers and hence wages rose and the landlords were unable to get their fields cultivated and in spite of legislative measures to resolve the problem a good deal of land simply reverted to grass. This contraction of the arable acreage continued through the late fourteenth century and the first half of the fifteenth. With the break-up of the manorial system a gradual consolidation of holdings took place mainly by exchange. Then too, the trend from a two field system of farming—one field under crop while one lay fallow—towards a three-course system of two fields under crop and one fallow became evident. Ultimately this system gave way to the four course system whereby grass appeared in the open fields which had hitherto been exclusively arable.

The Tudor period was marked by a spate of writings from farmers and historians, and such names as Fitzherbert, Tusser, Leland, Camden and Morden are an essential part of agricultural history. From them a clear picture of the husbandry of the time is obtained and it is quite evident that farmers were becoming very concerned about grass. The meadows of Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Devon and Somerset brought forth ecstatic praise and it is significant that by A.D. 1600 graziers were obviously men of substance, and wealthy classes of butchers and tanners were arising. The records of the period abound in such cases as the Earl of Derby, whose household in 1590 consumed 56 oxen and 535 sheep, while that of Sir William Fairfax in Yorkshire consumed 49 oxen and 150 sheep, and the household of the Bishop of Aberdeen consumed 48 oxen, 160 sheep, and 17 pigs. Fresh meat in winter was for the wealthy only, for the problem of feeding cattle and sheep on a large scale during the winter months still remained to be solved; the poor, when they had meat in winter, had to make do with salted. England lagged behind the times on this problem, for the value of turnips for cattle during the winter months was already appreciated in the Low Countries.

Wheat as an economic crop offers many attractions to farmers with suitable land and many of the enclosed pastures which had carried cattle and sheep for many years and had as a result increased appreciably in fertility were ploughed, and good yields were obtained which were markedly better than the medieval yield from the open fields, which was recorded as being a meagre 10 bushels per acre. A statute of 1597 had given official recognition to the fact that worn-out arable land regained its fertility when it was laid down to pasture and devoted to grazing stock for a number of years.

We do not know exactly when grass and clover became regarded as a crop and part of a recognised rotation. Richard Weston, a refugee from the Civil War, brought back from Holland a bag of red clover seed when he returned to England. The Spaniards had initiated the Dutch into the growing of red clover (Trifolium pratense) a century before and it was usually sown as a pure crop in the arable rotation. In 1653, Andrew Tarranton wrote The Great Improvement of Lands by Clover and, following much of the advice of Weston and Blyth, gave practical demonstrations of its value for stock feed, either when grazed or made into hay. He also managed to convey something of the fertility-restoring powers of clover and the immense increase in the stock-carrying capacity of clover pastures compared with ordinary grass. He instanced the need for careful control of the grazing to avoid the distressing trouble of “bloat” or “hoven” in which affected animals became “blown up” due to an accumulation of gas in the stomach resulting from failure of the mechanism which normally enables relief to be secured by belching. The trouble usually occurs when animals are suddenly introduced to young rich herbage and unfortunately it may prove fatal within an hour or so. (It is interesting to record that some three hundred years later we have not yet found a wholly reliable remedy.) Finally, he encouraged other farmers to visit him and see his ideas put into practice, and to-day we are broadly speaking still following the technique which he practised.

Progress was slow and more than a hundred years elapsed before the first stages in ley farming were generally adopted. The Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufactures and Commerce did much to encourage land improvement and indeed in 1763 imported the seed of cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata) from Virginia and also offered awards for the best herbage seed crops grown in this country. Benjamin Stillingfleet, in his Calendar of Flora 1762, invented English (as opposed to Latin) names for such species as had not already acquired them. Unfortunately, he included sweet vernal (Anthoxanthum odoratum) and other useless grasses amongst those recommended as valuable for agricultural purposes. This error was still unnoted 150 years later when excellent samples of this weed were offered for sale as a useful “bottom grass” by the agricultural merchants of the day.

The saving of good seed each year has been stressed by agricultural writers from earliest times. In the eighteenth century Coke of Norfolk and the Duke of Bedford employed children to go into the fields and hedgerows and collect the seed heads of different grasses when they were ripe, in order to have available a store of seed for sowing the following year.

During the latter half of the eighteenth century, agricultural progress was rapid. Tillage methods underwent revolutionary changes, substantial sums of money were invested in farm implements and machinery, in drainage and buildings, and every effort was made to improve both crops and livestock. Agricultural Societies were established all over the country and many of these are still in existence.

After the Napoleonic wars agriculture went into decline. The Board of Agriculture was dissolved in 1822.

When the virgin and fertile lands of the New World came into full production, causing a fall in world grain prices, the British farmer had to face a very real challenge. United Kingdom agriculture turned to dairy farming and animal husbandry generally. A good deal of land was allowed to revert to grass, buildings were not maintained, drainage was neglected, and sheep and cattle as alternative sources of income took the place of corn. By 1874, a vast acreage of arable land had been sown down to grass, no less than 1,688,487 acres between 1877 and 1884. Agriculturists were greatly concerned with the sowing down of land to permanent pasture and so we have J. Caird in his English Agriculture (1850) and M. H. Sutton (Laying Down Land to Permanent Pasture, 1861), J. Howard (Laying Down Land to Grass, 1880), C. de L. Faunce-De Laune (On Laying Land to Permanent Grass, 1882) and William Carruthers (On Laying Land to Permanent Grass, 1883) all in the Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society, devoting much attention to the problem but indicating at the same time that the tide would turn, that permanent grassland would again be ploughed for cropping and that the crops would be the better if good grassland had been established. The whole matter was summarised very effectively in Robert H. Elliott’s book The Clifton Park System of Farming (1898).

In 1889 the Board of Agriculture was re-established, and in 1896, the classical experiments at Cockle Park, Northumberland, were initiated to demonstrate the value of basic slag as a source of phosphoric acid for the grass sward. Basic slag, superphosphate, and combinations of lime, slag, potash and nitrate of soda were under trial, the merit of the fertiliser being assessed by the liveweight increase of sheep which grazed the plots, or by the weight of hay. The outstanding treatment was an application of 10 cwt. per acre of basic slag as a first dressing, followed by 5 cwt. per acre every third year afterwards and this treatment was adopted by large numbers of farmers throughout the country. The effect of the slag was to so encourage the growth of wild white clover that the stock-carrying capacity of the grassland was increased threefold. Even to-day, it is quite common to find farmers using slag in these amounts.

By now attention was being given to the value of native strains of grasses in addition to wild white clover, and work at the North of Scotland College of Agriculture, and by Professor A. N. McAlpine at Glasgow, had indicated something of the potential of grass output when the right types of grasses were linked to wise fertilising. In 1919, Lord Milford, by a generous gift to the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth, brought into being the Welsh Plant Breeding Station which, under its director Professor R. G. Stapledon, was to make a far-reaching contribution to the realm of grassland husbandry in the production of leafy, indigenous strains of the principal grasses. Their names to-day carry the prefix “S” and are known throughout the world.

Other land-marks in the history of grassland in this country are the establishment of Jealott’s Hill Research Station in Berkshire by Imperial Chemical Industries in 1936, the formation of the British Grassland Society in 1945, and the opening of the Grassland Research Institute at Hurley in Berkshire in 1949, the first station to be devoted solely to fundamental research problems in the sphere of grassland husbandry.

Spectacular progress has been made in British agriculture during the past quarter-century. It has become much more productive, has reached a high level of technical efficiency and is probably the most highly mechanised in the world. The acute dangers of two world wars and their aftermath have indicated the vital national need to reduce the dependence of a very large industrial population upon imported food supplies.