По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

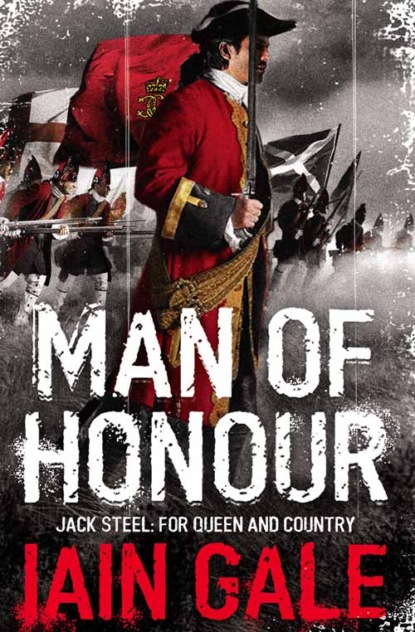

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The column came to a clanking, grinding stop. Steel spoke again:

‘Grenadiers. Forward.’

From behind him, Slaughter and the forward half-platoon of Grenadiers marched in double-time until they were directly to his rear, formed in two ranks.

‘Make ready.’

Steel heard the men cock the locks of their guns and knew that the first rank would now have fallen to their knees, placing the butts of their weapons on the ground with the second at the ready close behind. That should do it. The cavalry, to his consternation, continued to advance towards them at a walk and finally came to an abrupt halt. At the moment of doing so, every trooper of their first three ranks drew his sword. Very neat, thought Steel. Whoever you are, you are good. The officer at the head of this red-coated cavalry, probably Steel adduced, from his lace, a Captain, rode forward with his Lieutenant and another trooper. All three looked grim faced and confident. Like the rest of the troop, the trio were covered in dust and soot and looked utterly exhausted. Steel noticed the broad orange sash around the Captain’s waist. So, they were Dutch. He could guess only too well what their mission might have been. Having reached the head of the column, both of the dragoon officers doffed their hats – short caps of light-brown fur – and their gesture was returned by Steel and Williams. The Captain, a brawny, moustachioed man with two days’ growth of beard on his swarthy skin, spoke first, in thickly accented English:

‘Captain Matthias van der Voert of the regiment of dragoons van Coerland, in the army of the United Provinces, Sir. May I enquire who you are and what business you have here?’

‘Lieutenant Jack Steel, Sir. Of Sir James Farquharson’s Regiment of Foot, in the Army of her Britannic Majesty, Queen Anne. I am here on Lord Marlborough’s business, Captain. We have a consignment of flour to be delivered to the army. Vital provisions, you understand.’

A thought entered his mind. ‘Perhaps you might be able supplement our escort?’

The Captain gazed down the line of wagons and saw the thinly spread force of ill-at-ease infantrymen.

‘I see why you might ask me that favour, Lieutenant. You’re a sitting target like that. But I’m afraid that I really cannot be of any assistance. I am under orders to continue through this country, with my men. We cannot be diverted from our task.’

‘May I enquire then as to the nature of your task, Captain?’

‘We have orders to burn any sizeable village or town in Bavaria that we find still inhabited and to turn out its people into the countryside. It is, I understand, to be done at the express command of your Lord Marlborough.’

Steel nodded his head. It was just as he had presumed. He pointed to the column of smoke.

‘That then, I imagine, Captain must be your work up ahead.’

‘We burnt that town last night, Lieutenant. Cleared it, so to speak. There’s nothing much left. Except the inn and an old church. No one there but an old innkeeper and his daughter. Very pretty. He’s ill and she wouldn’t move him. But they’re quite harmless. Good beer though, if my men have left you any. The girl says that her father’s something to do with the English. His relative lives in England, or some such thing. You may find out more. Please, persuade them to leave, if you can, Lieutenant. Our orders were simply to move the people on and burn their houses. We want no part in killing civilians. We left them alone there, just burned the houses. That’s what we were told to do.’

He looked genuinely concerned, but was obviously ultimately confident that he had carried out his orders to the letter.

‘They should leave. We’re not alone here, this country’s full of troops. Ours and theirs. Dutch, English, French. I wouldn’t stay there if I were them. An old man and a girl. What can they do? They’re dead meat, Lieutenant. Or worse.’

Steel was suddenly aware of a commotion from the rear of the column. He looked back along its length and saw that Jennings was trotting towards them. He was mouthing unintelligible words. The Dutch officer saw him too.

‘You have another officer?’

‘My superior. Our Adjutant. He prefers to travel towards the rear.’

The Dutchman shook his head. The English army never ceased to amuse him. Pleasant men to be sure, but such amateurs. They wage no war for seven years and then they march into the continent and blithely expect to take command. Someone had even told him recently that the English were now claiming to have invented the new system of firing by platoon which the Dutch infantry had been using for at least five years. He laughed and Steel smiled back. Jennings grew closer.

‘Mister Steel. What’s this? Introduce me.’

‘Major Jennings, Captain van der Voert of the dragoons, in the army of our friends in the United Provinces.’

Jennings flashed a disarming smile at the Dutchman.

‘My dear Captain. How very fortunate. Now we shall all travel together. The country is teeming with French troops and brigands of every description. My own command was attacked and we have lately fought an action against Frenchmen of the foulest sort …’

Van der Voert cut him short.

‘Major, I am indeed alarmed to hear of your encounters. But I am afraid that we cannot be travelling companions. We have specific orders, direct from the high command of the allied army. We proceed due west, Sir, and canot divert from our course.’

Steel interjected:

‘The Captain is under orders from the Duke of Marlborough himself, Sir. He is to lay waste Bavaria.’

Jennings stared at Steel, tight-lipped.

‘Then clearly we must not delay the good Captain from his duty. Good day to you, Sir.’

The Dutchman nodded.

‘Herr Major, Lieutenant. I am afraid that we must leave you. We have pressing work, you know. Your Lord keeps us busy.’

Steel grimaced. The Captain touched his hat and the others followed suit, then he turned with his men and rode back to the troop. Closing with them, he barked a gutteral order and with an impressive single movement, the dragoons returned their swords to their scabbards. Jennings, without a word, turned his horse and trotted back towards the rear of the column. Steel turned to Slaughter.

‘Stand the men down, Sarn’t.’

He watched the Dutch Captain lead his men off the road and into the fields so that they might ride past Steel’s column to ease its passage.

Steel looked at Slaughter:

‘Come on, Sarn’t. Let’s get to the bloody town before that inn, if it really exists, burns down.’

He sighed. ‘Christ, Jacob. I hope we find the army soon. I’m not sure how much more of this I can take.’

‘Sir?’

‘Major Jennings, Sarn’t. You know well enough what I mean.’

Slaughter smiled.

‘I know, Sir. And I know that we shouldn’t still be down here. We need to get back to the regiment. And if we don’t get back soon I reckon we’ll not just miss whatever battle there is. We’ll miss the whole bloody war.’

The town of Sielenbach, when they finally arrived there, was nothing less than Steel had expected. A smoking, charred ruin of what had once been the pride of its citizens. The redcoats advanced carefully up the long main street, pausing briefly at every road junction to look both ways, before crossing and peering into the ragged rooms of every ruined house to make sure that no one had indeed been left to die.

Steel knew that the men were tired and, worse than that, thirsty and low in morale. For them this whole expedition had been an inexplicable loss of face. They had covered themselves in blood and glory at the Schellenberg, only to be sent on this sutler’s errand. Steel, they would have followed anywhere, given the prospect of action, but now they were deep in the Bavarian heartland, guarding a wagon train of flour. They had rescued a senior officer and a company of musketeers. Had beaten off an attack by as ruthless a bunch of Frenchmen as you could ever encounter, with no help it seemed from that same officer, their own Adjutant, who had himself recently carried out a ruthless and undeserved punishment on one of their number. They had discovered a terrible massacre and buried the dead, including women and babes, and now they saw towns being put to the torch by their own side and the ordinary people, people like themselves, being forced out into the countryside. Steel knew his men would be wondering what was going on and right now the last thing he wanted to do was answer questions.

The Grenadiers looked up to Steel and believed in him as much as they did in anything. They knew his war record, that he had served with the Swedes and come through that hell unscathed. There was something very special about Mister Steel. He was lucky and, like all soldiers who were deeply superstitious, they thought that perhaps some of his luck would rub off on them. But at the end of the day, he would always be an officer. Steel, too, felt the distance between them at times like this. Oh, he knew that he could rely upon Slaughter to keep them in order. But unless they rested – really rested and found their humour once more – he knew that he might all too easily have a mutiny on his hands.

For better or worse, Steel had taken the flogged man, Cussiter, into his half-company on the day following his punishment. The man had come to him personally and begged to be admitted. Cussiter had real spirit and Steel knew instinctively that, given time he would make a fine Grenadier. But Cussiter was also full of hatred, in particular for Farquharson and Jennings. Given the mood of the men, who knew what slight provocation might be needed for Cussiter to give way to his feelings. Here in the heart of enemy territory, where anything might happen, no one would ever be the wiser. It was better surely to pre-empt any trouble. Get to the damned inn – if it still stood. Stand each man a flagon or two of the local brew and let them get some rest. Soldiers were easy to handle, if you knew their ways. It was all very fine for Colonel James (or was it Septimus) Hawkins to tell his nephew that the key to being a good officer was to maintain respect, but Steel knew better. Keep them in good humour and they’d fight for you. Provoke them too strongly and you were as much a dead man as the nearest Frenchie.

Steel reined in and jumped down from the saddle. Best now to show solidarity, get down among them and lead by example. Besides, his status as an officer on entering a town might as well go to blazes here. He was hardly expecting a reception committee from the Mayor. Slaughter looked at him, equally cheerless.

‘Begging your pardon, Sir, but was you proposing that we would spend the night here? In this godforsaken blackened hole?’

‘That I was, Jacob. That I was. This is Sielenbach and it seems to me to be as fine a place as any to kick off your boots.’