По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

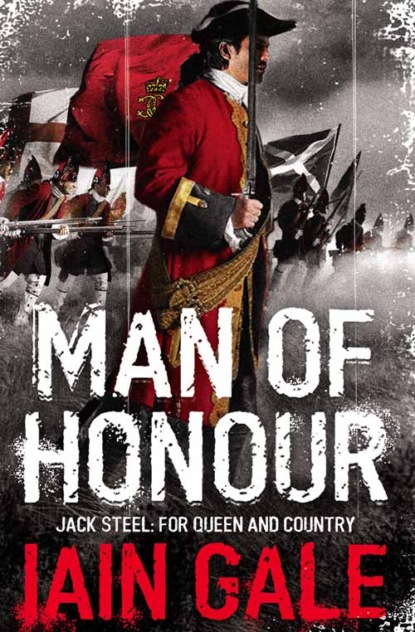

Jack Steel Adventure Series Books 1-3: Man of Honour, Rules of War, Brothers in Arms

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Steel goaded the horse into a trot and rode along to the where Williams led the column. ‘Looks a pretty little place, Tom, don’t it?’

They had started from their bivouac an hour ago, travelling more slowly now, on account of the wagon train. Not that they had woken late. It had taken a good two hours to bury all the dead, from both sides. It was around nine in the morning now and, as they grew closer to the village Steel noticed in the neighbouring fields the cattle grazing happily and carts standing half-filled with harvested produce.

‘Villagers seem to be at their breakfast, Sir.’

‘Perhaps they’ll save some for us, Tom, eh?’

As the redcoats entered what appeared to be the place’s major street a single sheepdog, who had been standing in the middle of the highway, barked a greeting and ran off to the left.

Steel looked up to the windows, waiting for the usual inquisitive faces to appear. For the children to run to greet them with taunting rhymes and begging gestures. Waiting for the doors of the houses to open. For the women to stand on the thresholds. For his men to whistle at the pretty ones and mock the ugly and the old. Would they be treated, he wondered, with condemnatory silence, or openly jeered. He hardly thought it likely they would have a warm welcome. What they received though exceeded all his expectations. The column advanced still further into the half-cobbled street, until it was almost at a tall stone cross, in the very heart of the little community. Still, though the half-timbered houses stood neat and silent in black-and-white perfection, the bright summer flowers pretty in their painted wooden boxes, no doors were opened. Steel raised his hand in command.

‘Company, halt.’

Everything was just as it should be. Beside a well-maintained water pump sat a clean pail, ready to be filled. Smoke curled up from the chimney of the inn to his right and from those of several other houses. He fancied that he caught the faint smell of cooking on the air. Cabbage. And something else – a strange aroma.

On one side of the village square, beyond the cross, stood a small church, a solid enough structure of stone and wood in the local style. He looked around to find any other building of authority. The church would do. Surely the priest would know what was going on. Grasping his pommel, Steel dismounted and, drawing his fusil from its sheath on the back of his saddle, he slung it over his shoulder.

‘Mister Williams. Stay here. I’m going to find someone. Sarn’t, with me.’

With measured step, Slaughter at his side, eyes searching the windows and surrounding lanes, Steel walked towards the church. Pushing gently at the door, he found it to be open. Inside was a cool haven. It was a simple basilica of plain stone, enlivened by two large and unremarkable oil paintings of obscure Catholic saints in grizzly attitudes of martyrdom. At the far end stood an altar whose gold ornament and richness of decoration were in profound contrast to the dun-hued stone. The place reeeked of incense and damp.

Steel yelled into the cool gloom: ‘Hello. Monsignor?’

His words echoed around the stones. The place was quite empty.

Nodding to Slaughter to follow him, he turned and walked out, back into the square.

Jennings had ridden up and was talking to Williams. Steel walked over to them. ‘No one in there. No priest. No one. Where the hell is everyone?’

Jennings gazed down at him with the supercilious disdain of someone to whom that conclusion had long been obvious.

‘Yes, I do wonder.’

He took a handkerchief from his sleeve and dabbed at his nose.

‘So, Mister Steel. What do you suggest that we do now? As you rightly observe the place appears to be deserted. Where, d’you suppose, is our contact?’

Steel, more bemused than irritated, shook his head. ‘I have no idea, Sir. Really. I can’t fathom it.’

‘Well we’d better find someone. Let me try.’

He turned in the saddle towards the rear of the column.

‘Stringer.’

The Sergeant came running, eager-eyed, from across the village square.

‘Sir.’

‘See if you can find someone in this godforsaken place. Anyone. Take … a platoon and search the houses. One by one. Kick down any doors that are locked.’

Steel turned to Williams. ‘Tom, rest the men here. Have them sit down. Ten minutes.’

Ignoring Jennings’ raised eyebrows, he looked at Slaughter. ‘Come on, Jacob.’

Steel unslung his gun from his shoulder and, holding it at the ready, began to walk with the Sergeant, up the road which led away from the church to the left, and from where he could still hear the sound of the howling dog. He looked down at the dusty cobbles. There had been movement here recently. The earth, which would normally have lain in a dust across the round stones, had been displaced so that they shone in the pale sunlight. A lot of movement by the look of it. Following the line of the exposed cobblestones he looked up the road, tracing the path of those who had gone before. Houses flanked either side of the narrow street and at the top, at the edge of a field, stood a large structure, simpler than the rest. A barn.

He turned to Slaughter. ‘Come on. Keep your eyes open.’

Slowly, the two men made their way up the hill. From below they could hear the splinter of wood as Stringer and his men kicked in the doors of locked houses. As they neared the edge of the village he looked at Slaughter and nodded in the direction of the timber-framed barn.

Quickly, Steel pushed open the door of the building and was barely over the threshold when he retched. Instinctively, although the place was quite dark, he closed his eyes. It was all he could do to avoid vomiting.

The smell was vile, but what met his gaze was far worse.

The barn was filled with bodies. Men, women and children, piled high upon one another. There must have been six score of them. All ages. And all were quite dead. He knew that without even troubling to look. Whoever had done this thing had been thorough. Not a sound came from the place save the buzzing of the flies that hovered and settled on the lifeless forms. Sattelberg had been a small farming township, with a population of barely 120 souls.

And here they were. Murdered in cold blood and left to rot.

Left, rather, thought Steel, with the specific intention that they should be discovered. This, he knew, was not the work of any of Marlborough’s men. But that was precisely what those who had done it wanted those who were meant to find the bodies to suppose. This had been meant to look like the work of British soldiers, but whoever had really done it had certainly not been counting upon their handiwork being discovered first by a company of genuine redcoats.

Yet, Steel asked himself, what sort of men could have done such a thing? This sort of atrocity had not taken place in Europe for almost a hundred years. Not since the wars of Gustavus. Could this really be the way that his own age would now go to war? The assault on Schellenberg had indeed made him think. But this new horror was quite another thing. He looked down at the bloody cadavers. Saw the leg of a young girl, not yet ten, he thought, protruding at a sickening angle from beneath the torso of a half-naked woman streaked with dried blood, presumably her dead mother, her arms still wrapped around the child. He forced himself to walk deeper into the gloom. Saw the body of a boy, the top of his head blown off, and that of a girl in her teens, a gaping hole in her back marking the exit of a musket ball. Tripping over outstretched, lifeless limbs to make his way back to the door, he found the corpse of the priest, tumbled into a corner. He had died from a sword cut to his head.

Steel staggered to the door. What sort of men killed innocents in this way? Not men at all. Mere beasts. Choking again on the stench, he pulled a handkerchief from his pocket and held it to his face. Calling out into the street, he struggled to get the words out of his dry mouth.

‘Sarn’t Slaughter. In here. Burial detail.’

Slaughter walked towards him and entered the barn. For a moment he stood speechless then, covering his mouth with his hand, spoke in a quiet voice:

‘Holy Christ, Sir. Sweet mother of God. The poor bastards. Who the bloody hell did this? Not the French, surely? Not soldiers? Eh?’

Steel gazed at the corpses and managed at last to speak. ‘Well, I don’t think, Jacob, that it was our men. And it surely couldn’t be the Bavarians themselves. This surely is the reason why Major Jennings was attacked by those peasants. It can only have been the French. D’you think?’

‘I’m learning not to think in this war, Mister Steel, Sir. Christ. Will you look at them. The poor wee babbies too. Holy Mother. It’s inhuman. Inhuman, Sir.’

‘And that’s just what we were meant to think, Sarn’t. And anyone else who might have found this. This wasn’t meant for us. But you’ve seen the smoke. Let’s say you were Bavarian and that you found this. What would you think? Who would you suppose had done it? What would you do?’

Slaughter froze. ‘I … I’d say that it was us that had done it, Sir. The English. Or at least them Dutch dragoons that’s been burnin’ the villages. I’d swear to kill any redcoats that I saw. Oh Christ. I see, Sir. The bastards.’

‘Of course you’d think that. And of course you’d want to kill the bloody English, wouldn’t you? And you’d come looking for any of us you could find.’

They turned and left the charnel-house, stunned momentarily by the sunlight.

Jennings was advancing towards them up the street, his face a mask of anger. ‘What the devil’s going on, Steel? We can find no one down in the village. We’ve got work to do. There’s no time to dally here. Where’s the bloody agent? Have you found him? What’re you doin’ up here?’

Then he noticed the open door of the barn. ‘I say, what’s in here?’

Jennings walked up to the door, pushed it open to enter and instantly wished he hadn’t. They heard the sound of him puking on the floor and, after a few moments, he emerged, wiping his mouth and ashen faced. He dabbed at his nose with the cologne-scented handkerchief and reached into his waistcoat pocket for his snuff box. Tucking a pinch of the brown powder into each nostril, he sneezed violently and then, after a few moments, turned to Steel.