По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

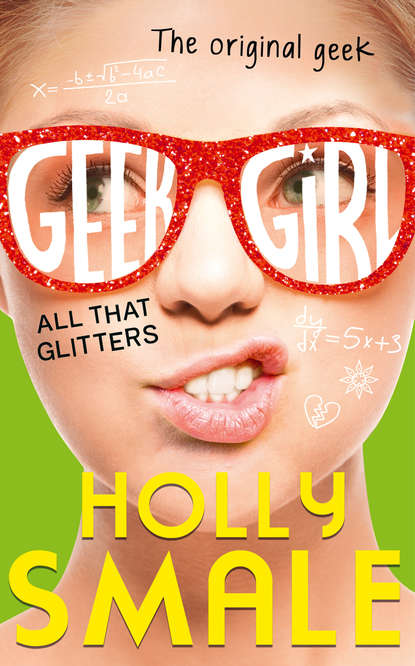

All That Glitters

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I’m obviously going to need every single one of them.

As I walk slowly home, every bush is stared at, every flowerpot glanced behind, every tree trunk checked. At one point I find myself making a little detour around a rubbish bin, just in case there’s somebody lurking there. Honestly, I haven’t behaved this weirdly since I went on a rampaging Flower Fairy hunt, aged six.

Or had so little success.

Because it doesn’t matter how hard I look, or how slowly I walk, or how many times I whisper I believe in you: it’s no good.

There’s nobody following.

Nobody listening, nobody watching.

For the first time in five years, Toby isn’t there.

“Dad?” I say as I push open the front door. “Tabitha? Did you have a nice d—”

I freeze.

Newspapers are strewn around the hallway. The sofa has been dismantled; blankets and clothes are scattered down the stairs. One living-room curtain is closed, every drawer is out, every cupboard is open. The rubbish bin is lying on its side: contents splurged all over the floor.

There are approximately 35,000 robberies reported every month in the UK, and it looks like we’ve just become one of them.

“Dad!” I shout in a panic, dropping my satchel. “Tabitha! Are you OK?”

What if they’ve taken my laptop?

Nobody will ever see the presentation I was making about pandas doing handstands.

“Dad!” I yell as I race into the bathroom. The medicine cupboard has been pulled apart. “Dad!” I yell in the kitchen where the fridge door is still open. “Dad!” I shout in the totally ransacked cupboard under the stairs. “Da—”

Dad walks in through the back door with Tabitha, snuggled up in his arms. “Daughter Number One! The conquering heroine returns!”

I fling myself at them so hard I may have crushed my little sister irreversibly. “Oh my goodness, you poor things. Did they hurt you? Did they threaten you? You could have been kidnapped!”

Actually, they may have been kidnapped and then returned. If I was a robber, I’d have brought my dad back pretty quickly too.

“Did the who which what now?”

“The burglars!”

“We’ve been burgled?” Dad says in alarm. “When did that happen? I was only in the garden for thirty seconds. Blimey, they move fast, don’t they?”

I look at him, and then at the chaos around us.

Now I come to think of it, nothing seems to be missing. It just appears to be … heavily rearranged. There isn’t a single cup left in the cupboard: they’re all sitting next to the sink, half full of cold tea. The plates aren’t gone: they’re just randomly distributed around the living room, covered in ketchup.

“You made all this mess?”

“What mess?” Dad glances around. “Looks fine to me. I tell you what, I don’t know what Annabel was going on about. This stay-at-home-parent malarkey is a doddle. I even wrote a poem after lunch. Do you want to hear it?”

“You wrote a poem?”

“I did indeed. I rhymed artisan with marzipan. And Tarzan.” Dad looks at my sister smugly. “We’re just trying to work out how to get partisan in there too, aren’t we, Tabs. I am partisan to a little marzipan while watching Tarzan.” He thinks about it. “If only it was Tarzipan. Such a shame.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: