По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

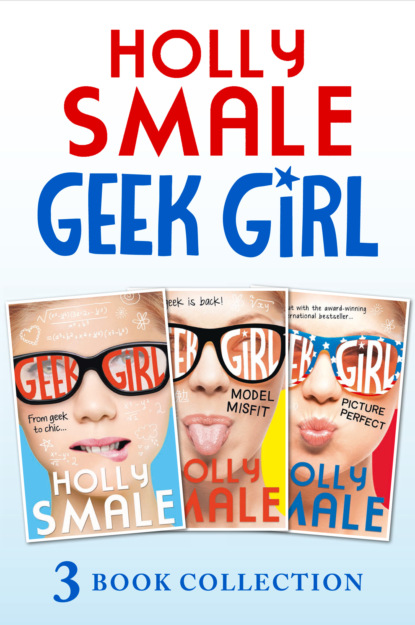

Geek Girl books 1-3: Geek Girl, Model Misfit and Picture Perfect

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Then…” and Annabel clears her throat, “I’ve bought you a present. I thought it might cheer you up.”

I look at Annabel in surprise. She rarely buys me presents, and when she does, they absolutely never cheer me up.

Annabel unfolds a large bag and hands it to me. “Actually, I bought this for you a while ago. I was waiting for the right moment and I think this might be it. You can wear it today.” And she unzips the bag.

I stare at the contents in shock. It’s a jacket. It’s grey and it’s tailored. It has a matching white shirt and a pencil skirt. It has very faint white pinstripe running through the material and a crease down each of the arms. It is, without any question of a doubt, a suit. Annabel’s gone and bought me a mini lawyer’s outfit. She wants me to turn up looking exactly like her, but twenty years younger.

“I guess you’re an adult now,” she says in a strange voice. “And this is what adults wear. What do you think?”

I think the modelling agency are going to assume we’re trying to sue them.

But as I open my mouth to tell Annabel I’d rather go as a spider with all eight legs attached, I look at her face. It’s so bright, and so eager, and so happy – this is so clearly some kind of Coming of Age moment for her – I can’t do it.

“I love it,” I say, crossing my fingers behind my back.

“You do? And you’ll wear it today?”

I swallow hard. I don’t know much about fashion, but I didn’t see many fifteen-year-olds last week in pinstripe suits.

“Yes,” I manage as enthusiastically as I can.

“Excellent,” Annabel beams at me, shoving some more bags in my direction. “Because I bought you a Filofax and briefcase to match.”

(#ulink_e019e017-dd58-558d-b728-7d4ccd001422)

he entire plan was a total waste of time. And Dad’s paper and printer ink.

By the time I’m dressed up like some kind of legal assistant and my parents have stopped fighting about Dad’s T-shirt (“It hasn’t even been washed, Richard,”; “I won’t bow down to the rules of fashion, Annabel,”; “But you’ll bow down to the rules of basic hygiene, right?”), we’ve missed our train and we’ve also missed the train after that.

When we eventually get to London, there isn’t time for a pain au chocolat or a cappuccino, and apparently, even if there was, I wouldn’t be allowed to have one.

“You’re not having coffee, Harriet,” Annabel says as I start whining outside the window.

“But Annabel…”

“No. You are fifteen and permanently anxious enough as it is.”

To make matters worse, when we finally locate the right street in Kensington, we can’t find the building: mainly because we’re not looking for a blob of cement tucked behind a local supermarket.

“It doesn’t look very…” Dad says doubtfully as we stand and stare at it suspiciously.

“I know,” Annabel agrees. “Do you think it’s…”

“No, it’s not dodgy. I saw it in the Guardian.”

“Maybe it’s nicer on the inside?” Annabel suggests.

“Ironic, for a modelling agency,” Dad says, then they both laugh and Annabel leans over and gives Dad a kiss, which means they’ve forgiven each other. Honestly, they’re like a pair of married goldfish: squabbling and then forgetting about it three minutes later.

“Well,” Annabel says slowly and she squeezes Dad’s hand a few times when she thinks I won’t notice. She takes a deep breath and looks at me. “I guess this is it then. Are you ready, Harriet?”

“Are you kidding me?” Dad says, ruffling my hair. “Fame, fortune, glory? She’s a Manners: she was born ready.” And – before I can even respond to such a shockingly incorrect statement – he adds, “Last one in is a total loser,” and runs to the door, dragging Annabel behind him.

Leaving me – shaking like the proverbial leaf in a very enthusiastic proverbial breeze – to sit down on the kerb, put my head between my knees and have a very non-proverbial panic attack.

(#ulink_c84627ce-3f46-58a6-a49e-d4d4bbb2b7d5)

fter a few minutes of heavy breathing, I’m still not particularly calm.

This might surprise you, but here’s a fact: people who plan things thoroughly aren’t particularly connected with reality. It seems like they are, but they’re not: they’re focusing on making things bite-size, instead of having to look at the whole picture. It’s procrastination in its purest form because it convinces everyone – including the person who’s doing it – that they are very sensible and in touch with reality when they’re not. They’re obsessed with cutting it up into little pieces so they can pretend that it’s not there at all.

The way that Nat nibbles at a burger so that she can pretend she’s not eating it, when actually she’s eating just as much of it as I would.

Despite my rigorous planning, I can’t break this down into any smaller pieces. Walking into a modelling agency and asking strangers to tell me objectively whether I’m pretty or not is one big scary mouthful, and the truth is I’m terrified.

So, just as I think things can’t get any worse, I abruptly start hyperventilating.

Hyperventilation is defined as a breathing state faster than five to eight litres a minute, and the best thing you can do when you’re hyperventilating is find a paper bag and breathe into it. This is because the accumulation of carbon dioxide from your exhaled breath will calm your heart rate down, and your breathing will therefore slow.

I haven’t got a paper bag, so I try a crisp packet, but the salt and vinegar smell makes me feel sick. I think about trying the plastic bag that came with the crisp packet, but realise that if I inhale too hard, I’m going to end up dragging it into my windpipe, and that would cause problems even for people who weren’t struggling to breathe in the first place. So, as a last resort, I close my eyes, cup my hands together and puff in and out of them instead.

I’ve been puffing into my hands for about thirty-five seconds when I hear a human kind of noise next to me.

“Go away,” I say weakly, continuing to blow in and out as hard as I can. I’m not interested in what Dad thinks. He plays games of Snap with himself when he’s stressed.

“This isn’t Singapore, you know,” a voice says. “You can’t just fling yourself around on the pavement. You’ll get chewing gum all over your suit.”

I abruptly stop puffing, but I keep my eyes closed because now I’m too embarrassed to open them again. My suit is grey and the pavement is also grey; perhaps if I stay very still and very quiet, I’ll disappear into the background and the owner of the voice will stop being able to see me.

It doesn’t work.

“So, Table Girl,” the voice continues, and for the second time today somebody I’m talking to is trying not to laugh. “What are you doing this time?”

It can’t be.

But it is.

I open one eye and peek through my fingers, and there – sitting on the kerb next to me – is Lion Boy.

(#ulink_bd0d81aa-0cf6-56b6-8275-7561149fac8f)

f all the people in the whole world I didn’t want to see me crouched on the floor in a pinstripe suit, hyperventilating into my hands, this one is at the top of the list.

Him and whoever hands out the Nobel Prizes. Just – you know. In case.

“Umm,” I say into my palms, thinking as quickly as I can. Hyperventilating doesn’t sound very good, so I finish with: “Sniffing my hands.”

Which, in hindsight, sounds even worse. “Not because I have smelly hands,” I add urgently. “Because I don’t.”