По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

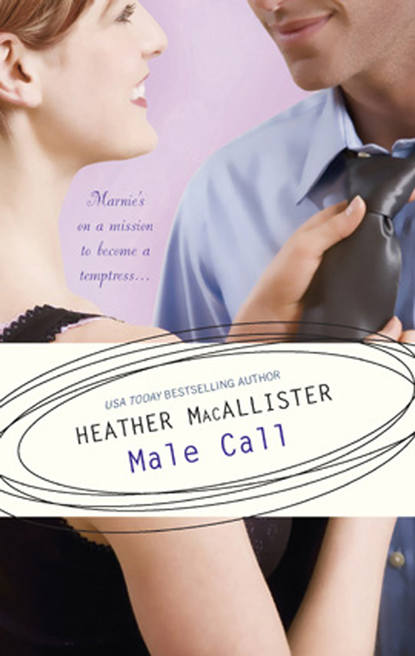

Male Call

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s so stupid,” she mumbled, holding the tissue against her nose.

“Not if it makes you cry.”

“Crying’s stupid, too.”

Franco sipped his tea and said nothing.

Eventually, Marnie couldn’t stand the sound of her sniffing in the silence and blurted out, “It’s just that a man at work, someone I thought I liked, told me I wasn’t girlfriend material, which I knew because the construction workers never whistle at me and I don’t even know why I care.”

She sniffed. Again.

Franco clasped his hands together. “May I take notes?”

“Why?”

“I’m a student of the human condition and hope to incorporate certain stories into my scripts.”

Great. She was a human condition. Marnie held her head in her hands. “I don’t care.”

“Does it matter if it becomes a film script?”

Like it would ever be produced. “No.”

Franco went to the telephone table and returned with a pen and pad of paper and began scribbling. “Now what else is bothering you?”

“My mother is going to Paris,” Marnie threw in for good measure. She’d just found out.

Franco gasped. “And not taking you?”

“She’s chaperoning the French club. She teaches high school.”

Franco gestured dismissively. “Consider yourself lucky, then. You don’t want Paris at this time of year. Now, what do you want?” He stared at the pad of paper. “Do I understand that you wish construction workers to objectify you?”

“No! Well, kinda… Actually, I guess I just want to be the sort of woman they would want to objectify—whistle at. You know.”

“I’m getting the idea, but please enlighten me.”

And so Marnie told him all about Barry and not being girlfriend material and the construction workers and the foreman thinking she was a homeless person. Franco nodded and said “Uh-huh” and “mmm” a lot as he took notes.

He was such a good listener that Marnie even told him how she’d worried about telling her mother she’d be staying here and how her mother had misunderstood and thought she was moving out and that her mom had been so happy that now Marnie was really going to have to look for somewhere else to live. None of this had anything to do with being girlfriend material, but Marnie had thought she was helping her mother by living with her and now her mother didn’t need help anymore and it was Just One More Thing.

“I’m sorry to be such a drama queen,” she moaned, holding her head.

“Drama is my life,” Franco said fervently. “What are you going to do?”

Marnie drank her entire mug of lukewarm tea. “I don’t know.”

“Yes, you do.” Franco tapped his pencil impatiently.

She did know. “Okay, but I don’t know how.”

“Oh, hon, you don’t want that Barry creature.”

“Oh, no. But I want him to ask me out to Tarantella. I want him to beg me.”

“And you want the construction workers to whistle at you.”

“Maybe just once.”

“I could pay them for you.”

Marnie laughed, then immediately sobered. “You’re saying that’s the only way—”

“No, it was a joke. A bad one. But I did make you laugh.” He studied her and Marnie was reminded of the construction foreman’s thorough scrutiny.

“We have a lot of work ahead of us.” Franco stood.

“We?”

“You didn’t think I wouldn’t respond to your cry for help, did you? We’ll start by doing your colors.”

“What?”

“We’ll ascertain which colors are most flattering to you before we go shopping, my little Cinderella.”

“Shopping isn’t one of my favorite words. I mostly order online.”

Franco gave a world-weary sigh. He used sighs very effectively. “I shall return with my swatches. You need to change.”

“I know.”

“I meant your clothes. What did you bring?”

Marnie looked down at herself. “Uh, more jeans. Some T-shirts.”

“Do you have a white T-shirt?”

“Mostly white. It’s got the blue writing on it from the Carnahan Easter 10K Fun Run.”

“Wear it backward or turn it inside out. And let me check my costumes—”

“You have costumes?”

“Yes, I’m an actor and a playwright and sometimes due to budgetary constraints in the small theaters, one must exercise many talents.” He headed for the door. “I’ll be back.”

Marnie cleared away the teacups and unpacked her suitcase. The closet was empty, except for a large hanging bag. She hung up three T-shirts, two pairs of jeans and her pajamas and robe. She didn’t know what to do with her underwear, so she left it in the duffel, which she set on the closet floor.

“Yoo-hoo,” she heard. Marnie couldn’t remember a time when she’d ever heard a grown man say “Yoo-hoo.”